Opinion » Comment

April 27, 2016 Updated: April 27, 2016 00:35 IST

A. Srivathsan

— Photo: By Special Arrangement

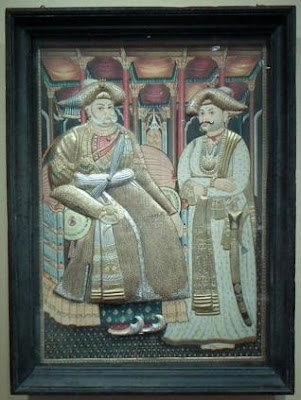

Database: “Providing sufficient information on theft cases has been a struggle.” A mid-19th century Thanjavur painting showing Serfoji II with Shivaji II was sold by Subhash Kapoor using false documents to Peabody Essex Museum in the U.S.

Database: “Providing sufficient information on theft cases has been a struggle.” A mid-19th century Thanjavur painting showing Serfoji II with Shivaji II was sold by Subhash Kapoor using false documents to Peabody Essex Museum in the U.S.

With poor documentation of existing and stolen artefacts, outdated laws, and unqualified investigative agencies, India’s record in preserving its past is deplorable

The Indian government’s response in the Kohinoor case has exposed its insensate ignorance. It not only got the facts wrong, but appeared embarrassingly out of depth in understanding restitution of antiquities. Given the poor track record in restitution, it seems unlikely that India will get the Kohinoor back. But the greater worry is its apathy towards antiquities. While countries such as Italy have not only successfully pursued stolen artefacts abroad but also effectively protected them locally, India, which is equally archaeologically rich and a victim of illicit trading, is far from it.

Studies have exhaustively documented the origins of the Kohinoor diamond in India, its complicated trail, and its eventual placement in the British royal crown. History does not leave to doubt that Lord Dalhousie forcefully acquired it from the young king Duleep Singh in 1849 when the East India Company annexed Punjab. Dalhousie compelled Singh to gift the diamond to Prince Albert and Queen Victoria as a “memorial of conquest”. However, later, as historian Danielle Kinsey’s research would show, Singh unsuccessfully demanded the return of the diamond.

Kohinoor was not the most spectacular stone in the Indian royal treasuries. Prof. Kinsey observed that Singh’s treasury, along with the Kohinoor, had the Darya-i-Noor, which was far more lustrous. But Lord Dalhousie knew the symbolic importance of the Kohinoor diamond and wanted it to be part of the Queen’s jewels. Prince Albert, equally aware of the lore, publicised its history and the Indian legends associated with it.

A puzzling stance

The historical and cultural significance of the Kohinoor, as in all other cases of antiquities, is what propels India’s demand for its return. The U.K. government has consistently refused to acknowledge this. This is expected, but the Indian government’s position has been puzzling.

Till the 1980s, India did not ask for the return of the Kohinoor diamond. By 2000 it changed its position and tried to “satisfactorily resolve” the issue. However, in 2010, after U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron visited India, it again changed its stand. To a question raised in Parliament in August 2010, the government categorically stated that Kohinoor was not covered “under the UNESCO’s Convention 1972 [sic] dealing with the restitution of cultural property”, and hence the question of recovery “does not arise”.

The 1970 UNESCO Convention prohibits illicit trading and transfer of ownership of cultural properties including antiquities. However, it does not cover any recovery claims of antiquities either smuggled or exported before 1970. This instantly puts a significant number of antiquities lost by colonised countries beyond any hope of return.

The government’s statement that the UNESCO Convention does not cover Kohinoor may appear legally right, but its belief that the year 1970 is ironclad is short-sighted. By conceding so, it also misses out the cultural, political and ethical dimensions of restitution.

Historian Elazar Barakan demonstrated in his insightful writings that restitution is not a legal category but a cultural concept which defines international morality. Loot and plunder may have been a practice in earlier times, but not anymore. It was 1815 that was the turning point, he wrote, when European powers agreed that the plundering of national art was “immoral and illegal”. However, this agreement was limited to European countries, while the colonies were merrily plundered. When the colonised countries became independent, they rightfully demanded the return of looted artefacts.

As Prof. Barakan remarked: “The need for restitution to past victims has become a major part of national politics and international diplomacy.” It has become a way of correcting historical injustices. The Indian government, taking cues from such arguments, should build a mature understanding of restitution rather than hastily draft myopic responses.

Whenever countries of origin demand the return of their stolen antiquities, museums and Western experts have refused. They have repeatedly derided that antiquities are not safe in the countries of origin. These specious arguments can be rejected. However, the fact remains that antiquities are not adequately cared for in India.

Information on theft

To start with, simple things, such as an integrated database of existing and stolen artefacts, hardly exist. Providing sufficient information regarding theft cases has been a struggle. For instance, to a question raised in Parliament in 2010 about the number of antiquities stolen, the government provided a list of 13 thefts that occurred between 2007 and 2010. This list did not include that of Subhash Kapoor, an international antiquities dealer currently in prison for his alleged involvement in the theft of 18 idols from Tamil Nadu. The number of thefts reported also appears too few to be true.

Compare this with the accomplishment of the cultural heritage squad of Carabinieri, the Italian armed police force. It has built an impressive database of about 1.1 million missing artefacts. Set up in 1969, the Carabinieri is the most acclaimed police force in protecting antiquities. The officers are well-trained in art history, international law, and investigative techniques. In the last 45 years, the force has recovered more than 8,00,000 stolen artefacts within the country. The squad is also known for its aggressive pursuit of restitution cases.

Indian investigative agencies pale in comparison. At the national level, the Central Bureau of Investigation handles antiquities theft as a part of its special crimes division. The division also handles cases of economic offences as well as those relating to dowry deaths, murders, and so on. It has not built the capacity to deal with stolen antiquities. A few State governments have special wings as part of their police force, but these are also understaffed and unqualified.

National laws have not helped the cause either. The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972, mandates compulsory registration of antiquities. However, the process is so cumbersome that not many antiquities are registered. There is also fear that registration would attract unnecessary government attention, and prevent the legitimate transfer of the objects. As a result, a large number of private collectors do not register antiquities in their possession. The Act, which is meant to deter thefts, is outdated and has to be amended. Though the Justice Mukul Mudgal committee submitted a report recommending changes in 2011, the government is yet to take action.

The state of India’s museums is another sad story. The Comptroller and Auditor General of India’s Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities in 2013 had scathing remarks about the country’s poor acquisition, documentation and conservation systems. A government initiative to document antiquities in its collection has also not progressed well. In 2007, the Ministry of Culture launched the National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities to complete documentation of about 70,00,000 antiquities. Until 2014, it had documented only 8,00,000 artefacts. The audit also raised serious concerns about the “discrepancies in the number of antiquities reportedly available in museums” including the National Museum in Delhi.

If the government is serious about the future of Indian antiquities, it has to, without delay, overhaul woefully inadequate institutions and improve legal measures and ill-prepared investigative agencies.

A. Srivathsan is a professor at CEPT University, Ahmedabad. Views expressed are personal

April 27, 2016 Updated: April 27, 2016 00:35 IST

A. Srivathsan

— Photo: By Special Arrangement

Database: “Providing sufficient information on theft cases has been a struggle.” A mid-19th century Thanjavur painting showing Serfoji II with Shivaji II was sold by Subhash Kapoor using false documents to Peabody Essex Museum in the U.S.

Database: “Providing sufficient information on theft cases has been a struggle.” A mid-19th century Thanjavur painting showing Serfoji II with Shivaji II was sold by Subhash Kapoor using false documents to Peabody Essex Museum in the U.S.

With poor documentation of existing and stolen artefacts, outdated laws, and unqualified investigative agencies, India’s record in preserving its past is deplorable

The Indian government’s response in the Kohinoor case has exposed its insensate ignorance. It not only got the facts wrong, but appeared embarrassingly out of depth in understanding restitution of antiquities. Given the poor track record in restitution, it seems unlikely that India will get the Kohinoor back. But the greater worry is its apathy towards antiquities. While countries such as Italy have not only successfully pursued stolen artefacts abroad but also effectively protected them locally, India, which is equally archaeologically rich and a victim of illicit trading, is far from it.

Studies have exhaustively documented the origins of the Kohinoor diamond in India, its complicated trail, and its eventual placement in the British royal crown. History does not leave to doubt that Lord Dalhousie forcefully acquired it from the young king Duleep Singh in 1849 when the East India Company annexed Punjab. Dalhousie compelled Singh to gift the diamond to Prince Albert and Queen Victoria as a “memorial of conquest”. However, later, as historian Danielle Kinsey’s research would show, Singh unsuccessfully demanded the return of the diamond.

Kohinoor was not the most spectacular stone in the Indian royal treasuries. Prof. Kinsey observed that Singh’s treasury, along with the Kohinoor, had the Darya-i-Noor, which was far more lustrous. But Lord Dalhousie knew the symbolic importance of the Kohinoor diamond and wanted it to be part of the Queen’s jewels. Prince Albert, equally aware of the lore, publicised its history and the Indian legends associated with it.

A puzzling stance

The historical and cultural significance of the Kohinoor, as in all other cases of antiquities, is what propels India’s demand for its return. The U.K. government has consistently refused to acknowledge this. This is expected, but the Indian government’s position has been puzzling.

Till the 1980s, India did not ask for the return of the Kohinoor diamond. By 2000 it changed its position and tried to “satisfactorily resolve” the issue. However, in 2010, after U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron visited India, it again changed its stand. To a question raised in Parliament in August 2010, the government categorically stated that Kohinoor was not covered “under the UNESCO’s Convention 1972 [sic] dealing with the restitution of cultural property”, and hence the question of recovery “does not arise”.

The 1970 UNESCO Convention prohibits illicit trading and transfer of ownership of cultural properties including antiquities. However, it does not cover any recovery claims of antiquities either smuggled or exported before 1970. This instantly puts a significant number of antiquities lost by colonised countries beyond any hope of return.

The government’s statement that the UNESCO Convention does not cover Kohinoor may appear legally right, but its belief that the year 1970 is ironclad is short-sighted. By conceding so, it also misses out the cultural, political and ethical dimensions of restitution.

Historian Elazar Barakan demonstrated in his insightful writings that restitution is not a legal category but a cultural concept which defines international morality. Loot and plunder may have been a practice in earlier times, but not anymore. It was 1815 that was the turning point, he wrote, when European powers agreed that the plundering of national art was “immoral and illegal”. However, this agreement was limited to European countries, while the colonies were merrily plundered. When the colonised countries became independent, they rightfully demanded the return of looted artefacts.

As Prof. Barakan remarked: “The need for restitution to past victims has become a major part of national politics and international diplomacy.” It has become a way of correcting historical injustices. The Indian government, taking cues from such arguments, should build a mature understanding of restitution rather than hastily draft myopic responses.

Whenever countries of origin demand the return of their stolen antiquities, museums and Western experts have refused. They have repeatedly derided that antiquities are not safe in the countries of origin. These specious arguments can be rejected. However, the fact remains that antiquities are not adequately cared for in India.

Information on theft

To start with, simple things, such as an integrated database of existing and stolen artefacts, hardly exist. Providing sufficient information regarding theft cases has been a struggle. For instance, to a question raised in Parliament in 2010 about the number of antiquities stolen, the government provided a list of 13 thefts that occurred between 2007 and 2010. This list did not include that of Subhash Kapoor, an international antiquities dealer currently in prison for his alleged involvement in the theft of 18 idols from Tamil Nadu. The number of thefts reported also appears too few to be true.

Compare this with the accomplishment of the cultural heritage squad of Carabinieri, the Italian armed police force. It has built an impressive database of about 1.1 million missing artefacts. Set up in 1969, the Carabinieri is the most acclaimed police force in protecting antiquities. The officers are well-trained in art history, international law, and investigative techniques. In the last 45 years, the force has recovered more than 8,00,000 stolen artefacts within the country. The squad is also known for its aggressive pursuit of restitution cases.

Indian investigative agencies pale in comparison. At the national level, the Central Bureau of Investigation handles antiquities theft as a part of its special crimes division. The division also handles cases of economic offences as well as those relating to dowry deaths, murders, and so on. It has not built the capacity to deal with stolen antiquities. A few State governments have special wings as part of their police force, but these are also understaffed and unqualified.

National laws have not helped the cause either. The Antiquities and Art Treasures Act, 1972, mandates compulsory registration of antiquities. However, the process is so cumbersome that not many antiquities are registered. There is also fear that registration would attract unnecessary government attention, and prevent the legitimate transfer of the objects. As a result, a large number of private collectors do not register antiquities in their possession. The Act, which is meant to deter thefts, is outdated and has to be amended. Though the Justice Mukul Mudgal committee submitted a report recommending changes in 2011, the government is yet to take action.

The state of India’s museums is another sad story. The Comptroller and Auditor General of India’s Performance Audit of Preservation and Conservation of Monuments and Antiquities in 2013 had scathing remarks about the country’s poor acquisition, documentation and conservation systems. A government initiative to document antiquities in its collection has also not progressed well. In 2007, the Ministry of Culture launched the National Mission on Monuments and Antiquities to complete documentation of about 70,00,000 antiquities. Until 2014, it had documented only 8,00,000 artefacts. The audit also raised serious concerns about the “discrepancies in the number of antiquities reportedly available in museums” including the National Museum in Delhi.

If the government is serious about the future of Indian antiquities, it has to, without delay, overhaul woefully inadequate institutions and improve legal measures and ill-prepared investigative agencies.

A. Srivathsan is a professor at CEPT University, Ahmedabad. Views expressed are personal

Source: thehindu