First Words

By LAILA LALAMI NOV. 21, 2016

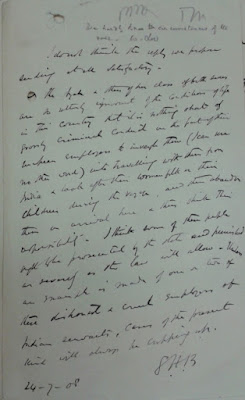

Illustration by Javier Jaén

Three years ago, I read “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” to my daughter. She smiled as she heard about Huck’s mischief, his jokes, his dress-up games, but it was his relationship with the runaway slave Jim that intrigued her most. Huck and Jim travel together as Jim seeks his freedom; at times, Huck wrestles with his decision to help. In the end, Tom Sawyer concocts an elaborate scheme for Jim’s release.

When we finished the book, my daughter had a question: Why didn’t Tom just tell Jim the truth — that Miss Watson had already freed him in her will? She is not alone in asking; scholars have long debated this issue. One answer lies in white identity, which needs black identity in order to define itself, and therefore cannot exist without it.

“Identity” is a vexing word. It is racial or sexual or national or religious or all those things at once. Sometimes it is proudly claimed, other times hidden or denied. But the word is almost never applied to whiteness. Racial identity is taken to be exclusive to people of color: When we speak about race, it is in connection with African-Americans or Latinos or Asians or Native People or some other group that has been designated a minority. “White” is seen as the default, the absence of race. In school curriculums, one month is reserved for the study of black history, while the rest of the year is just plain history; people will tell you they are fans of black or Latin music, but few will claim they love white music.

This year’s election has disturbed that silence. The president-elect earned the votes of a majority of white people while running a campaign that explicitly and consistently appealed to white identity and anxiety. At the heart of this anxiety is white people’s increasing awareness that they will become a statistical minority in this country within a generation. The paradox is that they have no language to speak about their own identity. “White” is a category that has afforded them an evasion from race, rather than an opportunity to confront it.

In his campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump regularly tied America’s problems to others. Immigration must be reformed, he told us, to stop the rapists and drug dealers coming here from Mexico. Terrorism could be stopped by banning Muslims from entering the country. The big banks would not be held in check by his opponent, whose picture he tweeted alongside a Star of David. The only people that the president-elect never faulted for anything were whites. These people he spoke of not as an indistinguishable mass but as a multitude of individuals, victims of a system that was increasingly rigged against them.

A common refrain in the days after the election was “Not all his voters are racist.” But this will not do, because those voters chose a candidate who promised them relief from their problems at the expense of other races. They may claim innocence now, but it seems to me that when a leading chapter of the Ku Klux Klan announces plans to hold a victory parade for the president-elect, the time for innocence is long past.

Racism is a necessary explanation for what happened on Nov. 8, but it is not a sufficient one. Last February, when the subject of racial identity came up at the Democratic primary debate in Milwaukee, the moderator Gwen Ifill surprised many viewers by asking about white voters: “By the middle of this century, the nation is going to be majority nonwhite,” she said. “Our public schools are already there. If working-class white Americans are about to be outnumbered, are already underemployed in many cases, and one study found they are dying sooner, don’t they have a reason to be resentful?”

Hillary Clinton said she was concerned about every community, including white communities “where we are seeing an increase in alcoholism, addiction, earlier deaths.” She said she planned to revitalize what she called “coal country” and explore spending more in communities with persistent generational poverty. Senator Bernie Sanders took a different view: “We can talk about it as a racial issue,” he said. “But it is a general economic issue.” Workers of all races, he said, have been hurt by trade deals like Nafta. “We need to start paying attention to the needs of working families in this country.”

This resonated with me: I, too, come from the working class, and from the significant portion of it that is not white. Neither of my parents went to college. Still, they managed to put their children through school and buy a home — a life that, for many in the working class, is impossible now. Nine months after that debate, we have found out exactly how much attention we should have been paying such families. The same white working-class voters who re-elected Obama four years ago did not cast their ballots for Clinton this year. These voters suffer from economic disadvantages even as they enjoy racial advantages. But it is impossible for them to notice these racial advantages if they live in rural areas where everyone around them is white. What they perceive instead is the cruel sense of being forgotten by the political class and condescended to by the cultural one.

While poor white voters are being scrutinized now, less attention has been paid to voters who are white and rich. White voters flocked to Trump by a wide margin, and he won a majority of voters who earn more than $50,000 a year, despite their relative economic safety. A majority of white women chose him, too, even though more than a dozen women have accused him of sexual assault. No, the top issue that drove Trump’s voters to the polls was not the economy — more voters concerned about that went to Clinton. It was immigration, an issue on which we’ve abandoned serious debate and become engulfed in sensational stories about rapists crossing the southern border or the pending imposition of Shariah law in the Midwest.

If whiteness is no longer the default and is to be treated as an identity — even, soon, a “minority” — then perhaps it is time white people considered the disadvantages of being a race. The next time a white man bombs an abortion clinic or goes on a shooting rampage on a college campus, white people might have to be lectured on religious tolerance and called upon to denounce the violent extremists in their midst. The opioid epidemic in today’s white communities could be treated the way we once treated the crack epidemic in black ones — not as a failure of the government to take care of its people but as a failure of the race. The fact that this has not happened, nor is it likely to, only serves as evidence that white Americans can still escape race.

Much has been made about privilege in this election. I will readily admit to many privileges. I have employer-provided health care. I live in a nice suburb. I am not dependent on government benefits. But I am also an immigrant and a person of color and a Muslim. On the night of the election, I was away from my family. Speaking to them on the phone, I could hear the terror in my daughter’s voice as the returns came in. The next morning, her friends at school, most of them Asian or Jewish or Hispanic, were in tears. My daughter called on the phone. “He can’t make us leave, right?” she asked. “We’re citizens.”

My husband and I did our best to quiet her fears. No, we said. He cannot make us leave. But every time I have thought about this conversation — and I have thought about it dozens of times, in my sleepless nights since the election — I have felt less certain. For all the privileges I can pass on to my daughter, there is one I cannot: whiteness.

Laila Lalami is the author, most recently, of “The Moor’s Account,” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Source: nytimes

By LAILA LALAMI NOV. 21, 2016

Illustration by Javier Jaén

Three years ago, I read “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” to my daughter. She smiled as she heard about Huck’s mischief, his jokes, his dress-up games, but it was his relationship with the runaway slave Jim that intrigued her most. Huck and Jim travel together as Jim seeks his freedom; at times, Huck wrestles with his decision to help. In the end, Tom Sawyer concocts an elaborate scheme for Jim’s release.

When we finished the book, my daughter had a question: Why didn’t Tom just tell Jim the truth — that Miss Watson had already freed him in her will? She is not alone in asking; scholars have long debated this issue. One answer lies in white identity, which needs black identity in order to define itself, and therefore cannot exist without it.

“Identity” is a vexing word. It is racial or sexual or national or religious or all those things at once. Sometimes it is proudly claimed, other times hidden or denied. But the word is almost never applied to whiteness. Racial identity is taken to be exclusive to people of color: When we speak about race, it is in connection with African-Americans or Latinos or Asians or Native People or some other group that has been designated a minority. “White” is seen as the default, the absence of race. In school curriculums, one month is reserved for the study of black history, while the rest of the year is just plain history; people will tell you they are fans of black or Latin music, but few will claim they love white music.

This year’s election has disturbed that silence. The president-elect earned the votes of a majority of white people while running a campaign that explicitly and consistently appealed to white identity and anxiety. At the heart of this anxiety is white people’s increasing awareness that they will become a statistical minority in this country within a generation. The paradox is that they have no language to speak about their own identity. “White” is a category that has afforded them an evasion from race, rather than an opportunity to confront it.

In his campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump regularly tied America’s problems to others. Immigration must be reformed, he told us, to stop the rapists and drug dealers coming here from Mexico. Terrorism could be stopped by banning Muslims from entering the country. The big banks would not be held in check by his opponent, whose picture he tweeted alongside a Star of David. The only people that the president-elect never faulted for anything were whites. These people he spoke of not as an indistinguishable mass but as a multitude of individuals, victims of a system that was increasingly rigged against them.

A common refrain in the days after the election was “Not all his voters are racist.” But this will not do, because those voters chose a candidate who promised them relief from their problems at the expense of other races. They may claim innocence now, but it seems to me that when a leading chapter of the Ku Klux Klan announces plans to hold a victory parade for the president-elect, the time for innocence is long past.

Racism is a necessary explanation for what happened on Nov. 8, but it is not a sufficient one. Last February, when the subject of racial identity came up at the Democratic primary debate in Milwaukee, the moderator Gwen Ifill surprised many viewers by asking about white voters: “By the middle of this century, the nation is going to be majority nonwhite,” she said. “Our public schools are already there. If working-class white Americans are about to be outnumbered, are already underemployed in many cases, and one study found they are dying sooner, don’t they have a reason to be resentful?”

Hillary Clinton said she was concerned about every community, including white communities “where we are seeing an increase in alcoholism, addiction, earlier deaths.” She said she planned to revitalize what she called “coal country” and explore spending more in communities with persistent generational poverty. Senator Bernie Sanders took a different view: “We can talk about it as a racial issue,” he said. “But it is a general economic issue.” Workers of all races, he said, have been hurt by trade deals like Nafta. “We need to start paying attention to the needs of working families in this country.”

This resonated with me: I, too, come from the working class, and from the significant portion of it that is not white. Neither of my parents went to college. Still, they managed to put their children through school and buy a home — a life that, for many in the working class, is impossible now. Nine months after that debate, we have found out exactly how much attention we should have been paying such families. The same white working-class voters who re-elected Obama four years ago did not cast their ballots for Clinton this year. These voters suffer from economic disadvantages even as they enjoy racial advantages. But it is impossible for them to notice these racial advantages if they live in rural areas where everyone around them is white. What they perceive instead is the cruel sense of being forgotten by the political class and condescended to by the cultural one.

While poor white voters are being scrutinized now, less attention has been paid to voters who are white and rich. White voters flocked to Trump by a wide margin, and he won a majority of voters who earn more than $50,000 a year, despite their relative economic safety. A majority of white women chose him, too, even though more than a dozen women have accused him of sexual assault. No, the top issue that drove Trump’s voters to the polls was not the economy — more voters concerned about that went to Clinton. It was immigration, an issue on which we’ve abandoned serious debate and become engulfed in sensational stories about rapists crossing the southern border or the pending imposition of Shariah law in the Midwest.

If whiteness is no longer the default and is to be treated as an identity — even, soon, a “minority” — then perhaps it is time white people considered the disadvantages of being a race. The next time a white man bombs an abortion clinic or goes on a shooting rampage on a college campus, white people might have to be lectured on religious tolerance and called upon to denounce the violent extremists in their midst. The opioid epidemic in today’s white communities could be treated the way we once treated the crack epidemic in black ones — not as a failure of the government to take care of its people but as a failure of the race. The fact that this has not happened, nor is it likely to, only serves as evidence that white Americans can still escape race.

Much has been made about privilege in this election. I will readily admit to many privileges. I have employer-provided health care. I live in a nice suburb. I am not dependent on government benefits. But I am also an immigrant and a person of color and a Muslim. On the night of the election, I was away from my family. Speaking to them on the phone, I could hear the terror in my daughter’s voice as the returns came in. The next morning, her friends at school, most of them Asian or Jewish or Hispanic, were in tears. My daughter called on the phone. “He can’t make us leave, right?” she asked. “We’re citizens.”

My husband and I did our best to quiet her fears. No, we said. He cannot make us leave. But every time I have thought about this conversation — and I have thought about it dozens of times, in my sleepless nights since the election — I have felt less certain. For all the privileges I can pass on to my daughter, there is one I cannot: whiteness.

Laila Lalami is the author, most recently, of “The Moor’s Account,” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Source: nytimes