Valentine's Day

Hamida Bano grew up to be a feisty queen and loyal wife, but when she first met her husband, she was just an angry teen.

Rana Safvi Feb 14, 2017

Hamida Bano was a 14-year-old when Humayun Badshah, 33, met her in Pat, a town in Sehewan in the kingdom of Thatta, in 1541. Having been defeated by Sher Shah Suri in the battle of Kannauj, Humayun was on the run – he had lost the kingdom his father Babur had established in India and along with his half brother Hindal, he took refuge with Shah Hussain, the Sultan of Thatta in Sind.

After many days spent travelling through perilous and desolate deserts, they had finally found some peace. Humayun’s stepmother Dildar Bano, who was Hindal’s mother, gave a banquet in his honour and among the guests she invited, was the beautiful Hamida.

Hamida’s father Sheikh Ali Akbar, a Persian sufi more popularly known as Mir Baba Dost, was Hindal’s spiritual instructor, and there was a close bond between him and the family. As soon as Humayun saw Hamida Bano, he asked his stepmother Dildar, “Who is this?” He was mesmerised by the beauty and liveliness of the teenager and asked if she was already betrothed. On hearing that she was not, he expressed the desire to marry her.

Mirza Hindal was affronted. Not because, as some stories and texts say, he was in love with her – but because he was concerned about the family name.

“I look on this girl as a sister and child of my own,” he is believed to have said. “Your Majesty is a king – heaven forbid there should not be a proper meher, and so a cause of annoyance should rise.” Meher is a mandatory payment in the form of money or possessions paid or promised by the groom, or the groom’s father, to the bride at the time of marriage, which legally becomes her property. Hindal was concerned that an emperor on the run may not have enough resources for this endowment to his bride at the time of nikah, or their wedding.

Emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

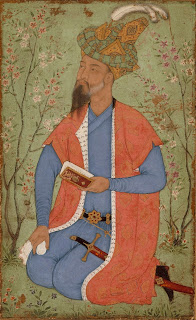

Hindal Mirza, the younger half brother of the second Mughal emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Read more: scrollin

Hamida Bano grew up to be a feisty queen and loyal wife, but when she first met her husband, she was just an angry teen.

Rana Safvi Feb 14, 2017

Hamida Bano was a 14-year-old when Humayun Badshah, 33, met her in Pat, a town in Sehewan in the kingdom of Thatta, in 1541. Having been defeated by Sher Shah Suri in the battle of Kannauj, Humayun was on the run – he had lost the kingdom his father Babur had established in India and along with his half brother Hindal, he took refuge with Shah Hussain, the Sultan of Thatta in Sind.

After many days spent travelling through perilous and desolate deserts, they had finally found some peace. Humayun’s stepmother Dildar Bano, who was Hindal’s mother, gave a banquet in his honour and among the guests she invited, was the beautiful Hamida.

Hamida’s father Sheikh Ali Akbar, a Persian sufi more popularly known as Mir Baba Dost, was Hindal’s spiritual instructor, and there was a close bond between him and the family. As soon as Humayun saw Hamida Bano, he asked his stepmother Dildar, “Who is this?” He was mesmerised by the beauty and liveliness of the teenager and asked if she was already betrothed. On hearing that she was not, he expressed the desire to marry her.

Mirza Hindal was affronted. Not because, as some stories and texts say, he was in love with her – but because he was concerned about the family name.

“I look on this girl as a sister and child of my own,” he is believed to have said. “Your Majesty is a king – heaven forbid there should not be a proper meher, and so a cause of annoyance should rise.” Meher is a mandatory payment in the form of money or possessions paid or promised by the groom, or the groom’s father, to the bride at the time of marriage, which legally becomes her property. Hindal was concerned that an emperor on the run may not have enough resources for this endowment to his bride at the time of nikah, or their wedding.

Emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Hindal Mirza, the younger half brother of the second Mughal emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Read more: scrollin