Seema Chishti

From Achhut Kanya in 1936 to Article 15 in 2019, how

Hindi cinema has looked at caste.

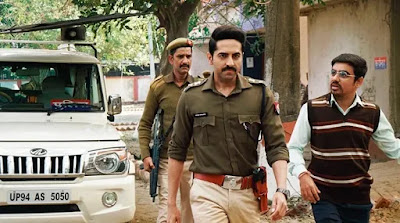

Across the Divide: Article 15 grows on you as a sophisticated whodunnit as its

central protagonist, a Brahmin, Stephanian IPS officer played by Ayushmann

Khurrana, tries to navigate caste hierarchies and maintain santulan or the status quo.

Billie

Holiday’s Strange Fruit (1939) is a rendition of a poem on racism in a

time when lynching of Black men was common in America. More recently, rapper

Kanye West used it in his album Yeezus (2013), the haunting lyrics

speaking of strung-up bodies of Blacks lynched for acting above or outside

their station and breaking the harsh code of the times: Southern trees bear

a strange fruit/Blood on the leaves and blood at the root/Black bodies swinging

in the southern breeze/Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

Strung-up

bodies serve as a warning universally. So, like in the deep south in the US, in

India, too, two minor Dalit girls, raped and murdered, were found strung on a

tree in Badaun in UP in 2014. Ever since he read a news report on it, filmmaker

Anubhav Sinha could not get the image out of his mind. He looked deeper into

the story and built a simmering narrative around it, of the system, its

politics, the acceptance of caste as well as the revolt against it in his

recently released film, Article 15.

Award-winning

BBC journalist Priyanka Dubey who has written powerfully on this case in her No

Nation for Women: Reportage of Rape from India, the World’s Largest Democracy

(2018), says, “Caste is an undeniable reality of today’s India and women’s

bodies are often used as a tool by upper-caste communities to prove their false

pride. My reporting experience on the Badaun double-murder case reinforced my

conviction that the road to justice becomes much tougher if the victim(s)’s

family belong to the ‘lower caste’ or are Dalits. I followed up the story till

after one year of the murders and the ruthless highhandedness with which the

investigative agencies behaved with the victims’ family made me feel that their

parents have absolutely no agency as citizens of this country.”

As far back as in 1936, the Ashok Kumar-Devika Rani

starrer Achhut Kanya told the

love story of a Dalit girl and a Brahmin boy, sundered by the caste system.

Article

15 grows on

you as a sophisticated whodunnit as its central protagonist, a Brahmin,

Stephanian IPS officer played by Ayushmann Khurrana, tries to navigate caste

hierarchies and maintain santulan or the status quo. But its strength

lies in its success in looking caste in the eye, unflinchingly.

Much before Article 15,

caste was explored in Hindi cinema — even before Independence. As far back as

in 1936, the Ashok Kumar-Devika Rani starrer Achhut Kanya told the

love story of a Dalit girl and a Brahmin boy, sundered by the caste system

while Bimal Roy’s Sujata in 1959 placed a Dalit character at its

centre. But essentially, the focus of these films remained on the personal

struggles of their Dalit characters and not on the issues that the the

community faced. It was left to Goutam Ghose to take on the issue in his

powerful Shabana Azmi-Naseeruddin Shah-Om

Puri starrer Paar in 1984.

A decade ago in 1974, Shyam Benegal

had trained his lens on feudal relations and the exploitation written

inherently in them in his directorial debut Ankur. Says Benegal of the

character played by Shabana Azmi who is betrayed at the end, “She was, of

course, Dalit, but at that time, no one used that phrase. The term, perhaps,

was also not much in use 40 years ago. It was more ‘us’ and ‘them’. Caste and

class were deeply interlinked then also, but things were not stated so

explicitly.”

More recently, down south, while Pa

Ranjith’s Rajinikant-starrer Kabali (2016) was a response to the 2012

Dharmapuri caste riots, Marathi film Sairat (2016) with its story of

young love and old barriers caught the imagination of cinema-goers outside

Maharashtra as well. But Sairat‘s remake in Hindi, Dhadak

(2018), a much watered-down version, showed just how Hindi cinema skirts around

the uncomfortable questions of caste and its reluctance to confront the full

horrors of it.

Though

there have been occasional films centred around Dalit characters like in Neeraj

Ghaywan’s sleeper hit Masaan (2015), Dalit characters are

mainly missing in Hindi cinema.

Though there have been occasional

films centred around Dalit characters like in Neeraj Ghaywan’s sleeper hit Masaan

(2015), Dalit characters are mainly missing in Hindi cinema. Says Dr Amit Thorat,

an economist who has written on exclusion and disparities faced by marginalised

groups, “I think Dalit heroes need to be represented more in popular cinema.

They also need to be presented as normalised in their social and personal

relationships.”

A common criticism against Sinha’s Article

15 has been on its choosing a Brahmin as its central protagonist. “I don’t

know if the film loses out by not having a Dalit hero. That would have been a

different film. In this film, I wanted the camera to enter the landscape from

the point of view of our young colleagues who think caste differences and

atrocities are a thing of the past. I wanted the camera to firmly rest on our

shoulders. It is addressed to all those who will make the New India in the next

10 years,” says Sinha.

How caste is chosen to be spoken

about in the news or in popular culture often shows us what exactly the issue

of the time was. The term ‘Harijan’ or ‘people of god’, eventually got negated

as patronising and was replaced by the term ‘Dalit’, popularised by Dr BR Ambedkar, that means

‘suppressed’ or ‘downtrodden’. But the films made then and even afterwards

steered clear of the term. “We were masters of shorthand then, with words, with

expression and how to show what was not stated upfront. People did not say, ‘I

am Dalit’ with pride then and if the term untouchable was used, it was like

abuse,” says Benegal.

Shorthand goes a long way today,

too. Sinha says this is the most arthouse he has gone in in any film, with

symbolism imbued in almost all shots of Article 15. Water,

particularly, is shown with a menacing air. “Throughout the film, water is

trouble. You don’t know what will be fished out from beneath. The shot of a

Dalit boy going down to clean the sewage is the only one which is 150 frames to

a second as I wanted the audience to be completely up close to him. We usually

think someone else cleans all the sewage. We have no awareness of the task he

performs,” says Sinha. Hindi cinema may be gradually beginning to train its

lens on these overlooked tasks but does, or can, a film like Article 15

show the full extent of the horrors of some Dalit lives?

Perhaps it can’t. Truth, after all,

remains stranger than fiction.

This

article appeared in the print edition with the headline ‘Anatomy of Atrocities’

Source: indianexpress