Features » Magazine March 26, 2016

A flag vendor tries to make a living by selling the tricolours and badges. Photo: K. Murali Kumar The Hindu

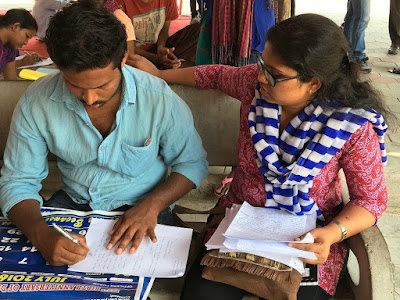

What does the idea of India mean to the ordinary people — the auto drivers and fishermen, students and shopkeepers, car drivers and homemakers?

In the wake of an increasingly shrill demand for demonstrative ‘nationalism’, the country has ranged itself on two distinct sides, each taking upon itself the onus of defining and laying down just what nationalism is, which anthems are more or less devoted, which symbols more significant, and which citizens can be awarded certificates as good, bad or middling patriots. In the ensuing noise of battle, what we have lost sight of is the middle ground, inhabited by the ordinary people, the auto drivers and fishermen, the students and shopkeepers, the car drivers and homemakers. What do they think? What does the idea of India mean to them? How do they demonstrate their love or loyalty? What is important to them? The Sunday Magazine team fanned out across the country to talk to this anonymous person on the street. And what we found was eye-opening.

From the fisherman in Chennai who said that before Bharat Mata he worships Kadal Mata (ocean mother) who gives him his daily bread to the tribal musician in Kerala who said making anthems compulsory in school is no guarantee to produce more patriotic students to the driver in Vellore who said that Jana Gana Mana has no religion, we discovered a quality of distilled and clear reality in the ordinary Indian’s thinking that is far removed from the unreal and harsh debate of primetime television and social media. Read on to hear their voices.

***

‘The bore-well is broken’

Shakuntala Soren (40), Santhali, Purulia, West Bengal

This Santhal woman from Shahajuri village, deep inside the Bengal-Jharkhand border, seeks help from her neighbours when asked about ‘nationalism’. “Weh ki?” (what is that?) she asks in Santhali.

Much explanation later, the word still makes no sense to her. So we ask if she knows the “identity” of her country. She looks around at her neighbours and then says “Bengal”.

And what about the national anthem? Soren looks restless. “Nolkup bari ekana,” she says. (“The bore-well is broken.”)

We turn to ‘Bharat mata ki jai’ and now the crowd gets restive. Someone shouts, “We don’t have work.”

A middle-aged man, Dhananjay Kisku, says they “barely survive” selling dry timber.

“I visit the forest too,” Soren says, and leaves to collect timber from the Ayodhya hills, a Maoist stronghold during the last elections five years ago.

- Suvojit Bagchi

‘Wasn’t Bharat a king?’

Mohammad Idrees Choudhary (47) , Dry fruit merchant, Bengaluru, Karnataka

Surrounded by neat packages of dry fruits imported from across the globe, Mohammad Idrees Choudhary, a 47-year-old merchant in the nearly 100-year-old Russel Market, explains what makes him an “Indian”. “At events and functions, I say: ‘Jai Hind, Jai Karnataka’ as a gratitude to the country and state that has allowed me to thrive. Now, with all this talk of ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, I am confused. Wasn’t Bharat a king? How can he suddenly be a mata? If I think ‘Jai Hind’ symbolises my patriotism better than ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, why should I be forced to say the latter?”

With poverty rampant and other pressing issues still affecting life, citizens do not have the time to repeatedly display their ‘patriotism’. “It is only politicians who seem to have all the time in the world to set these rules,” he says.

- Mohit M. Rao

‘Hatred is anti-national’

Drashti Shah (28), Entrepreneur, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

For Drashti Shah, patriotism or nationalism is about respect for the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution. “My definition of nationalism is to serve a new India that is visibly emerging from the fold of its many pasts. This new India needs to be seen with new eyes, free from the baggage of yesterday's political characterisations,” says Shah who is a designer and runs a café.

“A liberal and pluralistic democratic nation makes us a progressive and self-confident country,” she says. Anything that promotes violence or hatred, says Shah, is anti-national.

- Mahesh Langa

‘My slogan is Jai Bheem'

Premnath Dhingra (52), Sanitation worker, Meerut, UP

“For a sanitation worker, a Dalit who cleans toilets and streets, and who has struggled all his or her life for dignity, ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ has no meaning, says Premnath Dhingra, a sanitation workers’ leader in Meerut. “In fact, as a group that faced upper caste atrocities for centuries, I would say that this slogan is an insult for us because the Hindutva groups that are talking about ‘Bharat Mata’ hail the caste system and want to continue with the structures of injustice and untouchability. It was neither a slogan of Bhagat Singh nor Baba sahab (Ambedkar), nor even Mahatma Gandhi,” he says. For Dhingra,the very idea of questioning the nationalism of lawful citizens of the country is “problematic”.

“From what I know of history, I can say that ruling governments and ideologues have raised the issue of nationalism when they had to do something dangerous. One instance is Hitler.”

“Nationalism,” continues Dhingra, cannot be “a slogan or an abstract idea or a statue or just one symbol. For me, nationalism means talking about those living in the nation and working to ensure equality, liberty, social justice and the absence of corruption”

For Dhingra, the suspension of the MLA in Maharashtra is not only wrong but also illegal. “Not only Waris Pathan, even I would never say ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’. Why would I? For me, the slogan is ‘Jai Bheem’, which stands for the struggle of Dalits. But I would never advocate forcing ‘Jai Bheem’ on anybody,” says Dhingra.

- Mohammad Ali

‘Corruption is anti-national’

P. Kannadas (42), Toddy shopkeeper, Muthalamada, Kerala

A worker at a toddy parlour close to the Govindapuram border checkpost between Pollachi in Tamil Nadu and Palakkad in Kerala, P. Kannadas is also an amateur nature photographer and environmental activist. “My area is a composite of Tamil and Malayalam traditions. Many unskilled workers from North India, who work in the farms and factories of Pollachi and Palakkad, visit my shop every day. I don’t feel any difference based on region or language. I connect with them as a daily-wage worker who ekes out a living in a toddy shop. For me, the ability to relate with others is nationalism. Patriotism is not just jargon but an attempt to consider all Indians as equals irrespective of their class, community and other affiliations. Patriotism is not an end in itself. It must be a giant leap forward to achieve global citizen status.” For Kannadas, corruption and communalism are anti-national. “They are taking our society backwards to the dark ages. Nationalism is not about wearing a T-shirt carrying symbol of Bharat Mata. It is something that must help us broaden our perspective.”

- K.A. Shaji

‘Kadal Mata is my first loyalty'

R. Raju (45), Fisherman, Chennai, Tamil Nadu

R. Raju is still intently unknotting his fishing net when we begin talking. “What does desa bhakti (patriotism) mean to me?” he repeats my question. And then, as if on cue, the 45-year-old resident of Pattinapakkam, along Chennai’s Marina Beach, responds: “It’s like worshipping god.”

But when we come to the question of Bharat Mata, Raju is more contemplative. He turns around and points to the sea: “To me, Kadal Mata (ocean mother) is with whom my first loyalty lies. Everything else follows. Bharat mata, swamis and temples, whatever, whoever they may be.”

On a day when the catch is good Raju makes close to Rs. 1,000. “The ocean is the giver. That is how I have fed and clothed and educated my children, that is how I run my house.” For Raju, the ocean is clearly bigger than the nation.

- Divya Gandhi

‘Jana Gana Mana must be compulsory in schools’

Suresh Shaw (52), Street vendor, Kolkata, West Bengal

Suresh Shaw is not sure about the symbols of patriotism, but he is particularly fond of ‘Jana Gana Mana,’ which he used to sing at his local government school. A sports enthusiast, Shaw has played football in the first division league in Kolkata until poverty and family pressure forced him to give it up. Now Shaw sells vehicle accessories on the pavement. “I think the national anthem should be made compulsory in schools. This makes us more patriotic. We are able to express our love for the motherland,” he says. Patriotism, says Shaw, is to express deference to the nation, but being patriotic also means “having responsibility to stand beside your countrymen”.

- Shiv Sahay Singh

‘Patriotism is dwindling’

P. Ramesh (32),Shopkeeper, Vellore, Tamil Nadu

P. Ramesh says that patriotism has been dwindling over the years. “Not many understand what true patriotism is. When compared to earlier generations, the present generation gives less importance to patriotism. I am proud to be an Indian. Be Indian, buy Indian is what I believe in.”

Ramesh regrets that people vote for money but show less interest in being loyal to the nation. He says that singing the national anthem is a wonderful feeling.

“For me, listening to the national anthem or singing it is a chance to feel patriotism. Students should definitely sing the anthem everyday in school, as those few minutes are an opportunity to express our love for the nation.”

The businessman sees nothing wrong in chanting ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’. “There is a practice of saying ‘Jai Hind’ and ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ gives a different feeling. There is nothing wrong in saying it.”

What distresses him is engaging children in labour, alcoholism, and discrimination against women. “These are not good for the country. Child labour is an insult to the nation. Providing education to women is equal to educating the society,” he says.

- Serena Josephine M.

‘The debate is absurd’

Sheeba Ameer (55), Social worker, Thrissur, Kerala

As a social worker engaged in supplying free essential medicines to institutions housing people with disability, Sheeba Ameer believes the present debate on nationalism and patriotism involves a high dose of absurdity. “Those who have any doubt on nationalism must read the Indian Constitution. It has clearly defined nationalism as pluralistic and accommodative. The concept of nationalism envisaged in the constitution involves the right to dissent and the right to remain different,’’ she says.

“I come from an orthodox Muslim family and life so far was a relentless fight against fundamentalism of different hues. Intolerance has no religion. Nationalistic and patriotic feelings must not involve hate and intolerance. We must not allow obscurantists to define nationalism,” she says. According to Ameer, nationalism must not be something imposed on others by a brute majority.

“I don’t know what prevented the Maharashtra MLA from saying ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, but forcing one person to say something and punishing him for disobedience would not be ideal for a civilised world. We have to make our democracy more meaningful by ending hatred based on religion and narrow perceptions of nationality.”

K.A. Shaji

A flag vendor tries to make a living by selling the tricolours and badges. Photo: K. Murali Kumar The Hindu

What does the idea of India mean to the ordinary people — the auto drivers and fishermen, students and shopkeepers, car drivers and homemakers?

In the wake of an increasingly shrill demand for demonstrative ‘nationalism’, the country has ranged itself on two distinct sides, each taking upon itself the onus of defining and laying down just what nationalism is, which anthems are more or less devoted, which symbols more significant, and which citizens can be awarded certificates as good, bad or middling patriots. In the ensuing noise of battle, what we have lost sight of is the middle ground, inhabited by the ordinary people, the auto drivers and fishermen, the students and shopkeepers, the car drivers and homemakers. What do they think? What does the idea of India mean to them? How do they demonstrate their love or loyalty? What is important to them? The Sunday Magazine team fanned out across the country to talk to this anonymous person on the street. And what we found was eye-opening.

From the fisherman in Chennai who said that before Bharat Mata he worships Kadal Mata (ocean mother) who gives him his daily bread to the tribal musician in Kerala who said making anthems compulsory in school is no guarantee to produce more patriotic students to the driver in Vellore who said that Jana Gana Mana has no religion, we discovered a quality of distilled and clear reality in the ordinary Indian’s thinking that is far removed from the unreal and harsh debate of primetime television and social media. Read on to hear their voices.

***

‘The bore-well is broken’

Shakuntala Soren (40), Santhali, Purulia, West Bengal

This Santhal woman from Shahajuri village, deep inside the Bengal-Jharkhand border, seeks help from her neighbours when asked about ‘nationalism’. “Weh ki?” (what is that?) she asks in Santhali.

Much explanation later, the word still makes no sense to her. So we ask if she knows the “identity” of her country. She looks around at her neighbours and then says “Bengal”.

And what about the national anthem? Soren looks restless. “Nolkup bari ekana,” she says. (“The bore-well is broken.”)

We turn to ‘Bharat mata ki jai’ and now the crowd gets restive. Someone shouts, “We don’t have work.”

A middle-aged man, Dhananjay Kisku, says they “barely survive” selling dry timber.

“I visit the forest too,” Soren says, and leaves to collect timber from the Ayodhya hills, a Maoist stronghold during the last elections five years ago.

- Suvojit Bagchi

Mohammad Idrees Choudhary (47) , Dry fruit merchant, Bengaluru, Karnataka

Surrounded by neat packages of dry fruits imported from across the globe, Mohammad Idrees Choudhary, a 47-year-old merchant in the nearly 100-year-old Russel Market, explains what makes him an “Indian”. “At events and functions, I say: ‘Jai Hind, Jai Karnataka’ as a gratitude to the country and state that has allowed me to thrive. Now, with all this talk of ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, I am confused. Wasn’t Bharat a king? How can he suddenly be a mata? If I think ‘Jai Hind’ symbolises my patriotism better than ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, why should I be forced to say the latter?”

With poverty rampant and other pressing issues still affecting life, citizens do not have the time to repeatedly display their ‘patriotism’. “It is only politicians who seem to have all the time in the world to set these rules,” he says.

- Mohit M. Rao

Drashti Shah (28), Entrepreneur, Ahmedabad, Gujarat

For Drashti Shah, patriotism or nationalism is about respect for the fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution. “My definition of nationalism is to serve a new India that is visibly emerging from the fold of its many pasts. This new India needs to be seen with new eyes, free from the baggage of yesterday's political characterisations,” says Shah who is a designer and runs a café.

“A liberal and pluralistic democratic nation makes us a progressive and self-confident country,” she says. Anything that promotes violence or hatred, says Shah, is anti-national.

- Mahesh Langa

Premnath Dhingra (52), Sanitation worker, Meerut, UP

“For a sanitation worker, a Dalit who cleans toilets and streets, and who has struggled all his or her life for dignity, ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ has no meaning, says Premnath Dhingra, a sanitation workers’ leader in Meerut. “In fact, as a group that faced upper caste atrocities for centuries, I would say that this slogan is an insult for us because the Hindutva groups that are talking about ‘Bharat Mata’ hail the caste system and want to continue with the structures of injustice and untouchability. It was neither a slogan of Bhagat Singh nor Baba sahab (Ambedkar), nor even Mahatma Gandhi,” he says. For Dhingra,the very idea of questioning the nationalism of lawful citizens of the country is “problematic”.

“From what I know of history, I can say that ruling governments and ideologues have raised the issue of nationalism when they had to do something dangerous. One instance is Hitler.”

“Nationalism,” continues Dhingra, cannot be “a slogan or an abstract idea or a statue or just one symbol. For me, nationalism means talking about those living in the nation and working to ensure equality, liberty, social justice and the absence of corruption”

For Dhingra, the suspension of the MLA in Maharashtra is not only wrong but also illegal. “Not only Waris Pathan, even I would never say ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’. Why would I? For me, the slogan is ‘Jai Bheem’, which stands for the struggle of Dalits. But I would never advocate forcing ‘Jai Bheem’ on anybody,” says Dhingra.

- Mohammad Ali

P. Kannadas (42), Toddy shopkeeper, Muthalamada, Kerala

A worker at a toddy parlour close to the Govindapuram border checkpost between Pollachi in Tamil Nadu and Palakkad in Kerala, P. Kannadas is also an amateur nature photographer and environmental activist. “My area is a composite of Tamil and Malayalam traditions. Many unskilled workers from North India, who work in the farms and factories of Pollachi and Palakkad, visit my shop every day. I don’t feel any difference based on region or language. I connect with them as a daily-wage worker who ekes out a living in a toddy shop. For me, the ability to relate with others is nationalism. Patriotism is not just jargon but an attempt to consider all Indians as equals irrespective of their class, community and other affiliations. Patriotism is not an end in itself. It must be a giant leap forward to achieve global citizen status.” For Kannadas, corruption and communalism are anti-national. “They are taking our society backwards to the dark ages. Nationalism is not about wearing a T-shirt carrying symbol of Bharat Mata. It is something that must help us broaden our perspective.”

- K.A. Shaji

R. Raju (45), Fisherman, Chennai, Tamil Nadu

R. Raju is still intently unknotting his fishing net when we begin talking. “What does desa bhakti (patriotism) mean to me?” he repeats my question. And then, as if on cue, the 45-year-old resident of Pattinapakkam, along Chennai’s Marina Beach, responds: “It’s like worshipping god.”

But when we come to the question of Bharat Mata, Raju is more contemplative. He turns around and points to the sea: “To me, Kadal Mata (ocean mother) is with whom my first loyalty lies. Everything else follows. Bharat mata, swamis and temples, whatever, whoever they may be.”

On a day when the catch is good Raju makes close to Rs. 1,000. “The ocean is the giver. That is how I have fed and clothed and educated my children, that is how I run my house.” For Raju, the ocean is clearly bigger than the nation.

- Divya Gandhi

Suresh Shaw (52), Street vendor, Kolkata, West Bengal

Suresh Shaw is not sure about the symbols of patriotism, but he is particularly fond of ‘Jana Gana Mana,’ which he used to sing at his local government school. A sports enthusiast, Shaw has played football in the first division league in Kolkata until poverty and family pressure forced him to give it up. Now Shaw sells vehicle accessories on the pavement. “I think the national anthem should be made compulsory in schools. This makes us more patriotic. We are able to express our love for the motherland,” he says. Patriotism, says Shaw, is to express deference to the nation, but being patriotic also means “having responsibility to stand beside your countrymen”.

- Shiv Sahay Singh

P. Ramesh (32),Shopkeeper, Vellore, Tamil Nadu

P. Ramesh says that patriotism has been dwindling over the years. “Not many understand what true patriotism is. When compared to earlier generations, the present generation gives less importance to patriotism. I am proud to be an Indian. Be Indian, buy Indian is what I believe in.”

Ramesh regrets that people vote for money but show less interest in being loyal to the nation. He says that singing the national anthem is a wonderful feeling.

“For me, listening to the national anthem or singing it is a chance to feel patriotism. Students should definitely sing the anthem everyday in school, as those few minutes are an opportunity to express our love for the nation.”

The businessman sees nothing wrong in chanting ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’. “There is a practice of saying ‘Jai Hind’ and ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’ gives a different feeling. There is nothing wrong in saying it.”

What distresses him is engaging children in labour, alcoholism, and discrimination against women. “These are not good for the country. Child labour is an insult to the nation. Providing education to women is equal to educating the society,” he says.

- Serena Josephine M.

Sheeba Ameer (55), Social worker, Thrissur, Kerala

As a social worker engaged in supplying free essential medicines to institutions housing people with disability, Sheeba Ameer believes the present debate on nationalism and patriotism involves a high dose of absurdity. “Those who have any doubt on nationalism must read the Indian Constitution. It has clearly defined nationalism as pluralistic and accommodative. The concept of nationalism envisaged in the constitution involves the right to dissent and the right to remain different,’’ she says.

“I come from an orthodox Muslim family and life so far was a relentless fight against fundamentalism of different hues. Intolerance has no religion. Nationalistic and patriotic feelings must not involve hate and intolerance. We must not allow obscurantists to define nationalism,” she says. According to Ameer, nationalism must not be something imposed on others by a brute majority.

“I don’t know what prevented the Maharashtra MLA from saying ‘Bharat Mata ki Jai’, but forcing one person to say something and punishing him for disobedience would not be ideal for a civilised world. We have to make our democracy more meaningful by ending hatred based on religion and narrow perceptions of nationality.”

K.A. Shaji

Source: thehindu