NEW REPUBLIC

The violence, insecurity, and rage behind the man who has replaced Gandhi as the face of India.

The violence, insecurity, and rage behind the man who has replaced Gandhi as the face of India.

By

May 3, 2016

Sumit

Dayal / Prospekt

In September 2014, at Madison

Square Garden in New York, India’s prime minister, Narendra Modi, addressed a crowd of nearly 20,000 people. It was a sold-out spectacle worthy of a lush Bollywood production,

with dancers warming up the audience and giant screens flashing portraits of

Modi in the style of Shepard Fairey’s 2008 Barack Obama “Hope” posters. There

was a revolving stage, a speed portrait painter, and a bipartisan coterie of American

politicians, including senators Chuck Schumer and Robert Menendez, and

South Carolina governor Nikki Haley, who is of Indian descent.

When Modi appeared, dressed in

saffron, a color associated with the ascetic, martial traditions of Hinduism,

his first words were “Bharat Mata Ki,” an invocation of India as a Hindu

goddess that translates as “For Mother India.” The crowd, almost entirely

Indian-American, some with Hindu tikas dotting their foreheads, finished

the line for him. “Jai!” they shouted. (“Victory!”) “Bharat

Mata Ki Jai!” Then they broke out into the chant, “Modi, Modi, Modi!”

Modi’s hourlong speech touched on every element of the received

wisdom about India as a vibrant democracy and rising economic power. He spoke of its special prowess in information technology and

the particular role played by Indian-Americans in this. He spoke of India’s

youthful population, with 65 percent of its billion-plus people under 35; of Make

in India, a program that encapsulated his plans to transform the country into a

manufacturing powerhouse along the lines of China; and the ways in which his

humble origins and meteoric political ascent served as an example of what might

be possible in India today.

This address was followed by

many similar ones around the world, but it was the first to

establish on a global stage an idea that had been doing the rounds, in India,

in the Indian diaspora, and among Western nations keen to carry out business in

India: Modi and India were versions of each other, doppelgangers marching

through the world and conveying a new era. Even Barack Obama made

the comparison, writing in Time’s annual list of the hundred most

influential people in the world: “As a boy, Narendra Modi helped his father

sell tea to support their family. Today, he’s the leader of the world’s largest

democracy, and his life story—from poverty to prime minister—reflects the

dynamism and potential of India’s rise.”

Dynamism, potential, rise:

These are the states of being captured by the entwinement of India and Modi. In

the minds of India’s elite, and in that of an admiring, supportive West, India

has been rising for a while, ever since it fully embraced Western

capitalism in the early 1990s. Modi’s Madison Square Garden appearance was but

an expression of that ascendance, from slumdogs into millionaires. But Modi was

also in New York because of something that accompanies the rising India

narrative: the perplexing reality that having been rising for so long, India is

still not risen.

In the past 15 years, the top

1 percent of earners in India have increased their share of the country’s wealth from 36.8

percent to 53 percent, with the top 10 percent owning 76.3 percent, and yet

India remains a stunningly poor

country, riven with violence and brutal hierarchies, held together with shoddy infrastructure, and marked by the ravages of lopsided

growth, pollution, and climate change. Modi at Madison Square

Garden, then, stood for the promise that India’s rise would finally be

completed, the summit reached. It had not yet been achieved, but he would

change that. He would change it because he was an outsider, a man of humble origins, leading a political party—the Hindu right Bharatiya Janata Party

(BJP)—that had a few months earlier been given a clear electoral majority, the

first time for any Indian party in 30 years. He was at Madison Square Garden to mark this

triumph, and to declare himself the new Indian icon for a new Indian century.

Adulation and violence,

sanctimoniousness and abuse, are never far from Modi and his supporters.

Modi referred, naturally, to

the icon he had supplanted, the one from a previous century. Stumbling over

Gandhi’s first name, calling him “Mohanlal” instead of “Mohandas,” Modi compared Gandhi to the members of his audience, as a person

who had lived abroad as a diaspora Indian before returning to India. Modi’s

Gandhi, however, had nothing to do with anticolonial politics, mysticism, or

nonviolence. Those had been left behind with the old India, as demonstrated by

some of Modi’s supporters outside the venue. Gathered in large numbers, they heckled and jeered at the Indian television anchor Rajdeep Sardesai for being part of what they saw as the

liberal wing of the Indian media, which is ill-disposed toward Modi. To

Sardesai’s attempts to ask them questions, they responded with shouts of “Modi,

Modi, Modi.” When he retorted, “Did Mr. Modi tell you to behave badly? Did

America tell you to behave badly?” a brawl ensued, some of the men chanting, “Vande Mataram,” or “Praise Mother India,” while others

shouted, “Motherfucker.”

This episode could be seen as

an aberration, but the combination of adulation and violence, sanctimoniousness

and abuse, is never far from Modi and those who support him. It is, in fact,

the essence of his appeal. He is a representative Indian not merely because he

signifies potential, outsider status, and an Indian form of DIY upward

mobility, but also because he embodies violent sectarian and authoritarian

tendencies: so much a modern man belonging to the new century that he has

dispensed with the pacifism associated with Gandhi.

One could see that in the

jostling bodies and shouting faces gathered around the Indian television

anchor. At work, these clean-cut, middle-class Indian men in their saffron

t-shirts displaying Modi’s face probably exuded deference and respectability,

at least toward those they associated with power and wealth. But gathered in

numbers, with their puffed-up chests and clenched fists, they replicated what

they admired most about Modi—a kind of unmoored nihilism that dresses itself in

religious colors and acts through violence, that is ruthlessly authoritarian in

the face of diversity and dissent, and that imprints the brute force of its

majoritarianism wherever it is in power.

During his speech, Modi told

the crowd the story of an interpreter in Taiwan who had asked him if

India was a land of black magic, with snakes and snake charmers. This drew

nervous laughter from the men and women in their professional clothes. The

story was in a familiar genre, that of the Indian humiliated abroad, and can be

found even in Gandhi’s accounts of colonialism and racism when traveling to the

West. For Gandhi and his contemporaries (and in fact for all colonized,

marginalized cultures), that experience of humiliation had led sometimes to a kind

of nativism—a reaffirmation of the superior values of one’s humiliated

society—but it had also provoked an anticolonialism that was internationalist

in spirit, identifying with other marginalized groups.

But Modi was speaking for a

new India and to a new India, one obsessed with completing its rise as an

economic power. Neither the speaker nor the crowd acknowledged that snake

charming in India is an occupation based on caste, and that they were far

removed from such livelihoods. They were simply angry, afraid, and humiliated

that their Indianness could be tainted by such associations, and it is not hard

to empathize with that sense of being patronized. But where the anticolonial,

Gandhi-inspired Indian might have worn the snake-charmer tag as a badge of

pride, the new, Modi Indian merely wanted it destroyed. The new Indian

instinctively understood the point of Modi’s anecdote, which was that it was

set in Taiwan, not a Western country, but still ahead of India in terms of

modernity.

“Our country has become very

devalued,” Modi said. Cheers resounded through the stadium, the

well-dressed professionals at Madison Square Garden united in their common

sense of humiliation. Modi waited for the cheers to die down. Then he said,

“Our ancestors used to play with snakes. We play with the mouse.” The

applause this time was deafening. In the twist of a metaphor, Modi had restored

the honor of the nation and of all those present. India was not a nation of

snake charmers but of high-tech mouse managers. And Modi understood this,

because he too was an Indian driven by rage and humiliation, a newcomer to the

system and a latecomer to modernity, a leader who would transform India into a

land of Silicon Valley white magic, but who would retain its authentic Hindu

core.

Listening to the crowd

finishing off his call-and-response of “Bharat Mata Ki … ,” he said,

“Close both your fists and say it with full strength.” The crowd rose, fists clenched,

shouting out the promise of triumph, of victory: “Bharat Mata Ki Jai!”

In 1893, more than a century

before Modi appeared at Madison Square Garden, a Hindu preacher called Vivekananda arrived in Chicago. The popular version of the

story, as told in India, describes him as a solitary, charismatic figure

dressed in saffron robes and turban as he faced the harsh cold and desiccated

materialism of the West. The more prosaic, if still dramatic, truth is that

Vivekananda had come to attend the World’s Parliament of Religions, a sideshow to that year’s

World’s Fair. There were representatives from many religions at the parliament, hoping to speak to a West

relentless in the assertion of its double-barreled superiority, Christianity

and the Enlightenment. Soyen

Shaku, whose student D.T. Suzuki became the most famous Zen teacher in the

United States, came as part of a Japanese delegation. The Sinhalese preacher Anagarika Dharmapala was there representing Theravada

Buddhism. Mohammed Alexander Russell Webb, a former American consul

to the Philippines who had converted to Islam, spoke on the faith he had

embraced.

Vivekananda was a remarkable,

complex figure, introducing his distinct, modernized version of yoga and neo-Hinduism to the United States. But if his

legacy in the West was to be yoga, in India it would morph—helped, no doubt by

his early death at 39—into a muscular Hindu nationalism centered around the

idea that Hindus needed to become more aggressive in challenging both Islam and

the West. He became a symbol of the Hindu warrior monk who had gone into the West to conquer it

for Hinduism, an idea embodied loudly by Modi in his own self-presentation, especially

in the cross-armed pose and saffron turban he affected. And just as

Vivekananda, in this populist version, took the battle to the West, so did Modi

when he arrived at Madison Square Garden.

In India, it took an

organization and the onset of race-based nationalism in the early twentieth

century to give Vivekananda’s vision a more sinister touch and ultimately

connect it to Modi. Founded in 1925 in the central Indian city of Nagpur, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh

(RSS), the National Volunteer Organization, took Vivekananda’s ideas of Hindu

revival a step further, combining them with racial theories popular in the West

and drawing inspiration from the Italian Fascists and the Nazis. M.S. Golwalkar, who became

the chief of the RSS in 1940, wrote approvingly of Germany’s “purging the country of the

Semitic Races—the Jews,” and urged Hindus to manifest a similar “Race Spirit”

with Muslims. After India became independent in 1947, Nathuram Godse, a former

member of the RSS, assassinated Gandhi for being too conciliatory toward

Muslims and Pakistan. The RSS was banned briefly, but this was a blip in its steady expansion

from its base in the Western state of Maharashtra into neighboring Gujarat,

Modi’s home state, and beyond.

The RSS was known for its

secretive, cultlike tendencies; it kept no written fundraising records, and

produced a constitution only in 1949 as a condition for the lifting of its ban. It stayed away from anticolonial politics under the British

and maintained a distance from electoral politics in the decades following

independence. It focused, instead, on the ideal of an upper-caste Hindu society

within an unabashedly upper-caste, patriarchal Hindu nation. It recruited boys

between the ages of six and 18, using doctrinaire lectures and a routine of

paramilitary drills to mold their Hindu “Race Spirit,” while its adult members

were unleashed as shock troops in riots against Muslims. It

maintained links with Hindu-right political parties and Congress leaders

favorably inclined to its sectarian idea of India, but avoided direct involvement

in parliamentary politics, calling itself a social organization rather than a

political one.

This was the

organization—disciplined, secretive, tainted by its association with Gandhi’s

assassination and its role in sectarian riots—that Modi joined in 1958 as an eight-year-old in the provincial

Gujarati town of Vadnagar. He was the third of six children, from a family that

ran a tea shop at the railway station to supplement its

income from pressing and selling cooking oil. Leaving home as a teenager, Modi

wandered the country, possibly to escape living with the wife who had been

chosen for him in an arranged marriage at an early age—ironically, just the

sort of social practice defended by the Hindu right, despite legislative

attempts to make marriage and divorce more equitable, especially for Hindu

women—and from whom he remains estranged. He returned after a couple of years

to the Gujarati city of Ahmedabad, where he briefly ran a tea stall before

joining the RSS full-time. Modi soon completed the RSS’s one-month

officer-training program and became a pracharak, or organizer.

One can see the attractions of

the RSS for a young man like Modi, filled with ambition and intelligence but

without much education or opportunity. Its warrior-monk structure would offer

upward mobility and power even as its cultish ideology stoked a sense of

humiliation about the place of India in the world, and of Hindus within India.

Decades later, when Modi wrote a book entitled Jyotipunj (Beams of light) about the people he admired

most, his list would consist exclusively of RSS members, foremost among them the Hitler-loving Golwalkar. Modi rose

rapidly through the ranks of this organization, one not dissimilar—in its

paranoia, violence, and sense of victimization—to the Ku Klux Klan. There were

always questions about his egocentricism, such as his tendency to wear a beard

rather than the look encouraged by the RSS—military mustache or

clean-shaven—and his tendency to upstage his rivals, but he was an efficient

organizer in an outfit that needed these skills as it became more directly

involved in influencing electoral politics.

The RSS had always maintained

a loose affiliation with Hindu political parties. As the BJP emerged in the

1980s as the primary political party of the Hindu right, led by men who were also members of the

RSS, that relationship grew stronger, until the BJP, the RSS, and a range of

other Hindu-right organizations formed what in India is called the Sangh

parivar, or “Sangh Family.” The BJP’s task has been to provide the

political face of the Sangh parivar, while the RSS remains its shadowy

soul.

Modi, at the G-20

summit in Australia in 2014, has taken his place among the world’s leaders. Photograph by Mark Nolan/Getty

The Hindu right, especially

the BJP, grew in influence as the Congress, India’s main political party,

weakened. By the 1980s, the Congress, dominated by the Nehru-Gandhi family, had

begun to dabble in sectarian politics and Hindu

nationalism. When Indira Gandhi was assassinated by Sikh separatists in 1984,

senior Congress leaders, joined by RSS members, directed a pogrom against the Sikh minority that resulted in the death

of 2,700 people, according to official estimates. Rajiv

Gandhi, the next prime minister, took his mother’s sectarian politics further

while also beginning India’s tilt toward the United States and toward

information technology and a market-driven economy. This process would create a

new Indian elite that was both aggressive and insecure about its place in the

market economy, something it compensated for by reconfiguring itself as

narrowly Hindu.

The BJP profited from these

trends, using the RSS philosophy of Hindutva (Hindu-ness) plus the slogan, “Say with pride that we’re Hindus,” to go from

two seats in the national parliament in 1984 to 85 in 1989, beginning a steady rise that, after a brief dip in 2004 and 2009,

culminated in 282 seats, or 51.9 percent of the total, in the 2014 elections

that made Modi prime minister.

There were significant

opportunities for Modi as the Hindu right expanded its sectarian politics. The

first, and most pivotal, campaign of the Hindu right involved a movement in

1990 to rebuild a temple to Rama, the mythological hero of the Ramayana,

on the disputed site of the Babri Masjid, a sixteenth-century mosque in

Ayodhya, in northern India. The BJP leader at the time, L.K. Advani, rode a Toyota truck modified into a “chariot” around the country to rally Hindus to the cause,

starting his journey at Somnath in Gujarat, where a temple had been destroyed

in the eleventh century by a Central Asian Muslim invader, and traveling towards Babri Masjid.

Modi was RSS general secretary

at the time, a position that entailed directing the BJP from behind the scenes,

making sure that it was following the RSS’s agenda. He organized the opening

segment of the tour, and old photographs show him standing next to Advani on

the chariot. In a sign of things to come, the temple campaign went global,

shored up by other members of the Sangh Family, including the Vishwa Hindu Parishad (VHP), or

World Hindu Council,

which focuses much of its energies on the Indian diaspora in the West. Hindus

around the world were asked to donate bricks to build the temple to Ram. Bricks, some made

of gold, arrived from abroad as well as from hundreds of villages and towns in

India, and although Advani’s tour ended when he was arrested for inciting violence, the mobilization continued.

On December 6, 1992, Babri Masjid was leveled by a Hindu-right mob, setting off a spiral

of violence that resulted in the death of around 2,000 people.

The violence of the Ayodhya

campaign, the crudeness of depictions of Muslims as brutal invaders, the deft

use of political spectacle, and the targeting of all this toward a new Indian

elite both ambitious and insecure, were trends that Modi would embrace and

develop. In 1995, he became BJP national secretary and moved to Delhi, just as

India began its conversion to a full-fledged market economy and embarked on a

period of economic growth that would benefit the urban elites enormously. The

market, the nation, and Hindutva converged as the BJP won the elections in 1998, the new government carrying

out a series of nuclear tests to celebrate the victory. A year

later, it fought a brief war with Pakistan. The nuclear tests and the war were

promoted hysterically by media outlets that were consumed eagerly by a growing

urban elite, drawing in even liberal Indians who might have been uneasy about

the Ayodhya campaign but who liked the way this new India asserted itself on

the global stage.

In October 2001, Modi was

appointed chief minister of Gujarat by the BJP leadership in Delhi. It was the first

time an RSS pracharak had become chief executive of an Indian state.

The impact was apparent soon afterward. In February 2002, 59 Hindus returning

from the tenth-anniversary celebration of the destruction of Babri Masjid died

in a fire that broke out in a train compartment. Investigations would later

point to the fire originating inside the carriage, perhaps from a

malfunctioning cooking-gas cylinder, but the Hindu right accused Muslims of

storming the train and setting it on fire. Modi flew to the site. Orders were

given for the corpses to be brought to Ahmedabad in a convoy of trucks. The

corpses were then displayed in the open on the hospital grounds, apparently

for the purpose of postmortem examinations, as agitated crowds watched the

grisly spectacle.

A retaliatory campaign of

extermination by Hindu mobs against Muslims began hours later and lasted for

more than two months, resulting in the death of more than 1,000 people and the

displacement of 150,000. Women and girls were raped before being mutilated and

set on fire. Homes, shops, restaurants, and mosques were looted and burned. The attackers, reportedly guided by computer

printouts that listed the addresses of Muslim families, were on many

occasions aided by the police or led by legislators in Modi’s government. Many

of the killers were identified as belonging to various Hindu right

organizations. “Eighteen people from my family died,” a survivor of the

onslaught said in “We Have No Orders to Save You,” a 2002 report from Human

Rights Watch. “All the women died. My brother, my three sons, one girl, my

wife’s mother, they all died. My boys were aged ten, eight, and six. My girl

was twelve years old. The bodies were piled up. I recognized them from parts of

their clothes used for identification.”

Even by the macabre standards

of mass murder in India, there was something unusually disturbing about the

Gujarat massacres. They had taken place in a relatively prosperous state, among

people given to trade and business, rather than in a less-developed part of the

country where a link might be made between deprivation and rage. But this

connection in Gujarat, between economic prosperity and primal, sectarian

violence, became one of the defining aspects of Modi’s image, in India and

among the diaspora, one reaffirming the other, the pride of wealth meeting the

pride of identity.

Modi’s Gandhi had nothing to

do with anticolonialism or nonviolence. Those had been left behind with the old

India.

In the aftermath of the

massacres, Modi demonstrated not a shred of remorse or regret. In fact, he decided early

on to turn questions about the massacres and his role in them into an attack on

Gujarat, and on India, especially when the Bush administration decided, in

2005, to deny Modi a diplomatic visa and revoked his

tourist/business visa for the “particularly severe violations of religious

freedom” that had taken place under him.

In 2007, when asked by Karan

Thapar, the host of a show on the Indian television channel CNN-IBN, “Why can’t

you say that you regret the killings that happened? Why can’t you say maybe the

government should have done more to protect Muslims?” Modi walked out of the interview. In 2013, as he was emerging as

a prime ministerial candidate, Modi responded to a similar question with a

convoluted analogy. “If someone else is driving, and we are sitting in the back

seat, and even then if a small kutte ka baccha comes under the wheel, do

we feel pain or not? We do.” Reuters translated kutte ka baccha as “puppy,”

which, while technically accurate, missed the point: Kutte ka baccha, or

“progeny of a dog,” is an insult.

Modi also began to say that he

had been given “a clean chit” about his role in the massacres by a team

appointed by the Indian Supreme Court. His legions of supporters modified this

statement, endlessly repeating that the Supreme Court had cleared him of any

culpability in relation to the massacres. Jagdish Bhagwati and Arvind

Panagariya, economists at Columbia University, wrote to The Economist asserting this, arguing that what the

magazine had earlier called a “pogrom” was really a riot and that a quarter of

those killed were Hindus. In some ways, this response is almost as disturbing

as what happened during the massacres themselves. Modi’s supporters were

willing to ignore the question of responsibility for the sake of what they saw

as the higher priority of a new India, now a superpower respected by the West.

Large sections of the liberal Indian intelligentsia, writers and opinion

makers, have chosen to remain silent. And then there are those who approve of

Modi, knowing that he has been able to address all of new India’s fantasies and

fears in a way not achieved by any other comparable leader, taking it to great

heights as an emerging capitalist power, asserting its place in the world, and

unleashing its dark, nihilistic violence on marginalized people.

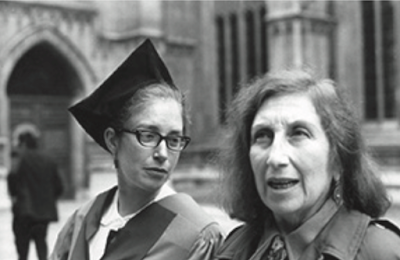

As for Modi’s “clean chit,”

the devil is in the details. Modi, who is supposed to have been absolved by the

Supreme Court, has never actually been tried by it. The Supreme Court was petitioned in 2008 by Citizens for Peace and Justice (CPJ),

an advocacy group seeking justice for the victims of the massacres. Led by

Teesta Setalvad, a Gujarati activist, the CPJ expressed its fear that the

judicial process in Gujarat was compromised, in response to which the Supreme

Court appointed a Special Investigation Team (SIT) to look into a

select number of cases. In 2009, the court also asked the SIT to investigate a petition against Modi related to his involvement

in the massacres, which was initiated by Zakia Jafri, whose husband, Ehsan

Jafri, a Congress politician, was killed

during them; she had previously approached the Gujarat police and the Gujarat

High Court to no avail.

The SIT’s final report in 2012

concluded that there was not enough evidence to prosecute

Modi. But, as the journalist Hartosh Singh Bal (my close friend and former

colleague) pointed out in Open, a current affairs magazine, those conclusions

differed dramatically from the evidence in the report itself. One is left with

the impression that the SIT was eager to find a lack of evidence no matter how

much evidence actually existed. Maybe the SIT was right to be cautious. Bal was

fired by Open just before the 2014 election for

being too critical of the Hindu right; when Modi won, Open described his

victory with the headline: “triumph of the will.”

The SIT was also plagued by

charges of interference from members seen as close to Modi and the Gujarat

administration. Harish Salve, a senior lawyer appointed to guide the SIT as an amicus curiae or “friend of the court,” was removed for

allegations of conflict of interest. He was also representing the Modi

government in front of the Gujarat High Court in the matter of Ishrat Jahan, a 19-year-old Muslim college

student who was killed by the police, who alleged she was a terrorist plotting

to assassinate Modi. There had been other such extrajudicial executions in

Gujarat, with more than 30 police officers and government ministers imprisoned for their involvement, all allegedly carried out

under the direction of Amit Shah,

the Gujarat minister of state during Modi’s tenure and now the president of the

BJP. A number of the police officers selected to join the SIT had allegedly

been involved in these extrajudicial killings, as well as in the 2002

massacres. Salve’s replacement, Raju Ramachandran, argued there was enough evidence to try Modi. He called for

the cross-examination of Sanjiv Bhatt, a Gujarat police officer who had earlier

stated that he was present at a meeting during which Modi directed the police

to allow Hindus to vent their rage.

The overall tendency of Modi’s

government was, as Human Rights Watch described in

its report, one of “subverting justice, protecting perpetrators, and

intimidating those promoting accountability.” Government officials seen as

loyal to Modi, and under whose watch some of the worst killings took place,

were rewarded with promotions and cushy posts. Those who

provided evidence that raised questions about his role in the massacres found

themselves subject to disciplinary measures, legal prosecution, threats, and

scandals.

Three police officers who gave

the National Commission for Minorities a transcript of a public speech

delivered by Modi seven months after the massacres, in which he called camps

set up for displaced Muslims “baby-producing centers,” were summarily transferred.

R.B. Sreekumar, a senior police officer who testified to a commission set up by

the Gujarat government to investigate the train fire and the massacres, which

was headed initially by a single retired judge considered to be a Modi

loyalist, was denied promotion and charged by the government with giving

out “classified information.” He had recorded a session during which a senior Modi official had

coached him about how he should answer questions, including “tell[ing] the

commission that no better steps could be taken” in terms of preventing the

violence. Rahul Sharma, a police officer who gave the commission phone records

allegedly proving that killers involved in the massacres had regularly been in

touch with politicians and police officers, was charged by the Gujarat government with violating the

state’s Official Secrets Act. Haren Pandya, a minister in the Gujarat

government who became a bitter rival of Modi’s, and who testified in secret to

an independent fact-finding panel about the riots, was murdered in March 2003, after he was publicly identified as

a whistle-blower and forced to resign his ministerial post. A dozen men,

supposedly Islamist terrorists, were arrested for Pandya’s murder; all of them

were acquitted eight years later. Pandya’s father maintained

that Modi had orchestrated the killing.

In contrast, those who were

indicted and sentenced to imprisonment for taking part in the massacres seemed

to have a benevolent, gentle state looking out for their well-being. Maya

Kodnani, an RSS member and BJP legislator, named by Modi as the Gujarat

Minister for Women and Child Development in 2007, was in 2012 sentenced to 28 years in prison for leading a mob that

killed 95 people, including 32 women and 33 children. In 2014, she was let out

on furlough due to poor health, and she has since been spotted

taking selfies at a yoga retreat on the outskirts of Ahmedabad.

Babu Bajrangi, a leader in the Bajrang Dal, a militant faction, who was also

convicted for his role in the Gujarat massacres, told the investigative magazine Tehelka in 2007 that

Modi was “a real man” who had changed judges on his behalf on a number of

occasions to get him out of jail. Given a life sentence in 2012, Bajrangi is frequently out of prison on furlough, for reasons ranging

from attending his niece’s wedding to getting his eyes checked.

The circumstances, when laid

down clearly, are so damning that it is astonishing that they can be airbrushed

from Modi’s record. But they show how, in Gujarat, Modi engineered a hybrid

vigilante-police state, one in which the righteous were punished and

perpetrators rewarded.

Modi ran Gujarat for more than

a decade. The achievements he claims from this period depend on audience and

situation, but they all emphasize his economic success, in particular the

“double-digit growth rates” he engineered through what is known as “the

Gujarat Model.” The profile

of Modi on the BJP web site commends his “masterstroke of putting Gujarat

on the global map” through an “ongoing campaign called the Vibrant Gujarat that

truly transforms Gujarat into one of the most preferred investment

destinations. The 2013 Vibrant Gujarat Summit drew participation from over 120

nations of the world, a commendable feat in itself.”

Muslims in Gujarat

gather after a night of Hindu rioting in 2002. Modi has refused to acknowledge

his role in fomenting the violence, which resulted in the death of more than

1,000 people, and attacked those who call him to account.Photograph by Ami Vitale/Getty

Modi hired the U.S. public

relations firm APCO

Worldwide to help promote the Vibrant Gujarat initiative, and in this too,

he showed himself to be a truly modern Indian, concerned with his image among

other nations of the world, particularly in the West. The West was a willing

accomplice in Modi’s ambitions, eager to turn the conversation away from

sectarianism and death by mob violence and toward the business opportunities

offered by the Gujarat model. In January 2015, The Economist, not particularly enamored of Modi,

lauded his fiscal success in Gujarat, writing, “With just 5 percent of India’s

population and 6 percent of its land mass, [Gujarat] accounts for 7.6 percent

of its GDP, almost a tenth of its workforce, and 22 percent of its exports.”

Loud expert voices, many of them in the diaspora, bolstered this triumphal

narrative, including Vivek Dehejia, an economist at Carleton University in

Ottawa; Bhagwati and Panagariya at Columbia; and Ashutosh Varshney, a political science professor at Brown.

As the 2014 national elections drew nearer, they were joined in their support

by more seemingly liberal figures, in India and abroad, who had in the past

been associated with the Congress.

When Modi was elected, Open

magazine described his victory with the headline: “Triumph of the Will.”

The truth about the Gujarat model was more complex. What had

been achieved, in a state that was already

more developed than many other parts of India, was a layer of

infrastructure and globalized trade—roads, power, exports—topped off with a

thick, treacly layer of hype. The state poverty figures under Modi remained unimpressive and employment levels stalled, while the quality of available jobs

went down, with lower wages in both rural and urban areas compared to the

national average. Almost half of Gujarat’s children under the age of five were

undernourished, in keeping with the shameful national average. (Panagariya, the Modi loyalist, argued that Indian children were stunted, even when

compared to impoverished sub-Saharan African populations, not because of

malnutrition, which was a “myth,” but because of genetic limitations to their

height.) The number of girls born in Gujarat compared to boys remains low, suggesting a continued bias for male children

in a country known for its grotesquely patriarchal norms; and yet the state is

in the forefront of providing surrogate mothers for wealthy Western populations.

Much was made of Modi’s

decision in 2008 to allow the Indian automobile manufacturer Tata to open a car factory in Gujarat, in particular after an

attempt to do so in the traditionally left-leaning state of West Bengal had

resulted in a violent farmers’ uprising.

Less was said, however, about the low-cost cars made at the Tata plant, which

were in the habit of catching fire. As for the rhetoric about creating

a new Singapore, Shanghai, or South Korea—Modi’s metaphors of growth reveal a preference

for authoritarian, homogeneous social systems—it has still remained rhetoric. A

new city on the outskirts of Ahmedabad, constructed by architects brought in

from Shanghai and touted, in 2012, as “the largest urbanization project in

Indian history,” turned out, three years later, as The Wall Street Journal reported, to consist of mostly

empty office buildings.

In an Independence Day speech

last August, Modi modified his “Make in India” slogan to a more contemporary “Startup India.” But there was little about the wealth

created under Modi that had to do with technological innovation. It depended

instead on heedless resource extraction, crony capitalism, and competition for

outsourcing work handed out by the West, all of which has been visible in India

for decades. In Modi’s case, this was exemplified by his closeness to the Gujarati billionaire Gautam Adani, who had

come swiftly to Modi’s defense when the latter was criticized for the 2002

massacres. In November 2014, Adani accompanied Modi to the G-20 summit in

Australia, a country in which he hoped to dig one of the largest, and most

controversial, coal mines in the world. Although a series of international

banks refused to fund the project, voicing concerns about its environmental

impact, Adani nevertheless received a massive loan from the State Bank of India.

The shortcomings of the

Gujarat model are not particular to the state but to India as a whole. The

difference is that Gujarat’s supposed economic achievement helped distinguish

Modi from other political leaders in India trying much the same things. So

Gujarat was a success, even as India was something of a failure to the Indian

elite supporting Modi—a paradox that was resolved by making him prime minister.

How, with the violent scandal

and the political failure, to account for Modi’s rise? The narrative of a

growing India fed into it, stoked by the Indian elite and a Western media

untrained to see nuances beyond the success of global capitalism in the

aftermath of the cold war. The outsourcing of Western IT and office services

played into it, as did the granting of visas to Indians to work in the West.

Even the rise of a security state targeting Muslims found deep echoes in the

West. The killing of Muslims in Gujarat in 2002 came less than a year after the

attacks of September 11, 2001, which meant that the old animosities of the

Hindu right towards Muslims, Islam, and Pakistan found fertile ground in a

United States whose wars abroad, in Afghanistan and then in Iraq, featured the

same enemies. India was an ally in the marketplace and in the war against

Islamism, and was a contrast to both the overly religious, anti-Western

militancy that would consume Pakistan and the godless manipulators of market

capitalism in China.

For many in the Indian

diaspora, and for their upper-tier elite relatives back in India, the endless

cover stories, op-ed articles, books, and films praising the new India—even as Islam, Muslims, and Pakistan

were regularly criticized as failed systems incompatible with modernity—meant a

kind of double bonus for their self-image, confirming their arrival as the

white man’s favorite kind of Indian. Thomas Friedman became a best-selling

author and a hero to Indians with his account of rising India in The World Is Flat. It was a long way from Henry

Kissinger’s comments in the 1970s that Indians were “bastards” and

Indira Gandhi a “bitch.” All of this had been achieved not through Gandhian

anticolonialism or the mystical self-abnegation associated with India by the

counterculture in 1960s America, but through the materialist terms acceptable

in contemporary America: money, long hours, and power.

The model minority status of

the Indian diaspora in the United States was an uneasy one. It depended on an

uncritical identification with the American ethos of success through work and

competition, as well as with its counterpart, what Toni Morrison has called the “most enduring and efficient rite of passage

into American culture: negative appraisals of the native-born black

population.” It meant attacks on the ideas of the welfare state, of affirmative action, of impoverished and

incarcerated minorities—a method transferable back home through Modi and the

Hindu right’s assault on minorities and the poor and contemporary India’s

valorization of wealth maximization and conspicuous consumption. But the truth

remained that India was not America, and the gilded elite of the former toasted

their lifestyles in a context of far greater poverty, surrounded by hundreds of millions of the dispossessed—potentially

militant and far too great in numbers to be housed in the prisons and

reservations favored by America. The status quo remained fragile, easily

disrupted, and it required not just a party or a program—the BJP’s rival, the

Congress, favored the same kind of economics and national security state—but a

strong man like Modi who could grasp the present in both fists, as he had done

in Gujarat. The West, with its selective talk of human rights, was an uncertain

ally in this respect, desirable for its power but also resented for its

superior status. Its approval, suddenly granted, could also be taken away,

denied as easily as the visa refused to Modi in 2005.

Modi, at the time, was planning to attend a U.S. trade convention of

Asian-American hotel owners. With 700,000 Gujaratis living in the United

States, probably the largest Indian group in the country, the State Department

was well aware of the sensitivities involved. A press

release about his visa denial noted “the great respect the United States

has for the many successful Gujaratis who live and work in the United States

and the thousands who are issued visas to the United States each month.” Yet

Gujarati support (and it is worth reiterating that many Gujaratis have resisted

Modi’s sectarian agenda at great cost to themselves) formed only one strand in

Modi’s valorization among Indians of Hindu origin in the diaspora,

regardless of their ethnicity. Indians from minority faiths (Muslims, Sikhs,

and Christians), and those belonging to progressive groups, kept a critical

distance from Modi. These groups were instrumental in pressuring the United States into denying him a visa, and

they later attempted to serve him with a legal summons for genocide during his triumphal visit to

Madison Square Garden.

For many in the Indian

diaspora, however, the denial of Modi’s visa highlighted the double standards

of the West, especially since the Bush administration was hardly a benign power

when it came to Muslims. It also confirmed the diaspora’s suspicion of liberal

factions in America, the media, universities, and the human rights sector,

which they believed were out to humiliate Indians and Hindus by pointing out

their deficiencies. The most visceral manifestation of these attitudes came in

the writings and talks produced by Rajiv

Malhotra, an Indian based in New Jersey who fulminated against the

conspiracy directed at Hindu India by Western academics in Western

universities. Like Modi, he saw himself as a mouse manager taken for a snake

charmer, a victim of those identified as enemies of Hindus by the RSS from its

very inception—Muslims, leftists, and the West. Malhotra, described by the Indian journalist Shoaib Daniyal as the

“Ayn Rand of internet Hindutva,” was an early exponent of the inverted

postcolonial doggerel common among Modi and his supporters. He spoke of

the “Eurocentric framework” of Western academics writing about an “indigenous

non-Western civilization,” while still himself uttering breathtaking

essentialisms about white women, India’s oppressed castes, African Americans,

and “Abrahamic religions.” Long influential among the Indian diaspora in the

United States, Malhotra had to wait for Modi to become prime minister to

achieve full respectability in India. But Malhotra, with his YouTube

videos, Twitter

feed, and enormously popular books (shadowed by accusations of plagiarism), was only the most obvious aspect of the

entrepreneurial approach to the Hindu-right project as manifested by

Indian-Americans.

This approach, which involved

think tanks, lobbies, social media, networking, and “nonpartisan” pressure

groups, added a new, globalized dimension to the established cultish practices

of the RSS and the mob politics of the BJP—something Modi grasped perfectly. He

liked his Indian-American experts for the global aura they gave him and for the

way they burnished his reputation as the Indian icon of the new century,

committed to running India in a way it had never been run before. So, while the

Indian diaspora’s main fixation in the United States was a kind of cultural

war—attempts to change references to Hinduism in school textbooks, smear

campaigns against Western scholars of Hinduism, and the introduction at

universities of programs and chairs in Hinduism that would be taught by individuals

with questionable scholarly credentials but possessing the vital attribute of

belonging to the faith—in India it would focus on bringing about Modi’s victory

in the national elections.

Modi’s electoral campaign,

described as India’s first “presidential” campaign, was carried out along American

lines with the focus as much on Modi as on his party. Lance Price, a former BBC

journalist turned spin doctor for Tony Blair, was brought in to write the story of the election; Andy Marino, an unknown

British writer, was given full access to Modi for an atrociously written hagiography that defended him on

everything, including the Gujarat massacres. The campaign also featured

the direct imprint of the Indian-American diaspora, including a purportedly

nonpartisan group called Citizens

for Accountable Governance (CAG). With members drawn from the alumni of

Columbia and Brown, and former employees of JP Morgan and Goldman Sachs, the

CAG provided data analysis and slick marketing tools for the campaign,

with holograms of Modi beamed, like some kind of Sith lord, into

distant Indian villages.

Yet beneath the modern,

entrepreneurial campaign, there remained the minority baiting, the majoritarian

aggressiveness, the riots, the intimidation, and the abuse. Among the crowds in

India, Modi, having first softened them up with populist language that stood in

direct contradiction to his business-friendly ethos in the boardrooms and

conference centers of the West, poured out his usual sectarian invective,

referring to himself as a sevak—a religious devotee. In the eastern part

of India, just days after more than 30 Muslims had been killed in

riots targeting them for their supposed origins in neighboring Bangladesh,

Modi, hands full of theatrical gestures, voice punctuated by dramatic pauses,

spoke of how after the elections and his victory, Bangladeshis in India would

have to pack

up their bags and leave.

Modi’s electoral campaign was

carried out along American lines, with the focus on him as much as his party.

It was done with expertise,

with subtlety, and always with an awareness of the business-friendly image

being promoted abroad. Amit Shah was put in charge of campaigning in the northern state of Uttar

Pradesh, an important arena for the national elections. Three months after he

took over, riots broke out between Hindus and Muslims, the majority of the dead

and the displaced being Muslims. Shah made sure, in a subsequent speech in April 2014, to accuse Muslims of

raping and killing Hindus and talked of the elections as an opportunity to

teach a lesson to the perpetrators of evil. The Election Commission of India,

which prohibits

appealing to voters on sectarian grounds, briefly banned Shah from campaigning, but Modi’s election drive

proceeded without a hitch.

As Modi went about his

business, wielding swords at rallies and berating “secularism,” the word used in India to emphasize its

constitutional principle of equal rights for all religious beliefs, his

devotees in India and the United States went about their mob business on the

internet and in the media and social media. There was the innovative abuse

directed at the 69 percent who would not vote for him, who did not buy into

his vision—the more polite terms being “presstitute,” “sickularist,” and “libtard.” The new

Indians boasted of Modi, of his manly 56-inch chest (it’s actually 44 inches, his waist 41,

and his belly 45, if his personal tailor is to be believed), but inches were

only another way of expressing Modi’s machismo. Teenagers tattooed images of Modi on their bodies, and he was lauded

as the country’s most eligible bachelor. The fact that he was in fact married, to a woman with whom he had never

lived, who has never been given financial support—and who, after Modi became

prime minister, would be denied a passport because she possessed no marriage

certificate—was largely forgotten, or drowned out with abuse and threats.

In an essay a few months after the Gujarat massacres, Ashis

Nandy, a clinical psychologist and one of India’s best-known public

intellectuals, recalled how he had interviewed Modi in the early ’90s, when he

was “a nobody, a small-time RSS pracharak trying to make it as a

small-time BJP functionary.” Nandy wrote, “It was a long, rambling interview,

but it left me in no doubt that here was a classic, clinical case of a fascist.

I never use the term ‘fascist’ as a term of abuse; to me it is a diagnostic

category.” Modi, Nandy wrote:

met virtually all the criteria

that psychiatrists, psychoanalysts, and psychologists had set up after years of

empirical work on the authoritarian personality. He had the same mix of

puritanical rigidity, narrowing of emotional life, massive use of the ego

defense of projection, denial, and fear of his own passions combined with

fantasies of violence—all set within the matrix of clear paranoid and obsessive

personality traits. I still remember the cool, measured tone in which he

elaborated a theory of cosmic conspiracy against India that painted every

Muslim as a suspected traitor and a potential terrorist.

Nandy soon found himself the

subject of a

criminal case lodged by the Gujarat police. It accused him, of all things,

of disturbing the harmonious relationship between religious communities. In a

way, it proved Nandy’s point about the authoritarian personality who attempts

to silence all dissent while expressing no doubts at all about his own actions

and beliefs. Vinod Jose, in a meticulously researched profile published in 2012 in Caravan magazine (I am

a contributing editor to Caravan), had noted how Modi made others

apologize, turning criticism into entrepreneurial opportunity. In February

2003, two Indian industrialists, at an event with Modi, commented on the

Gujarat violence; Modi engineered a written apology from the Confederation of

Indian Industry (CII), the trade association that had organized the event. “We,

in the CII, are very sorry for the hurt and pain you have felt,” the letter

stated, adding that it regretted “very much the misunderstanding that has

developed since the sixth of February, the day of our meeting in New Delhi.”

For those who have not

apologized, and who have continued to stand up to Modi, different measures have

been applied: legal intimidation, government pressure, social abuse, scurrilous

gossip, police cases, and mob violence. Setalvad, one of Modi’s staunchest

opponents, found her residence in Mumbai raided last July by the Central Bureau of Investigation, a

federal agency, even as the Gujarat government attempted to have her arrested

for financial fraud. The Ford Foundation, which has funded some of the projects

carried out by Setalvad’s organization, discovered itself in the crosshairs of both the federal

government and the state of Gujarat, the latter accusing the foundation, in a

repeat of the charges against Nandy, of “abetting communal disharmony.”

With a defeat in November’s state elections for Bihar, in the

eastern part of the country, Modi’s new India has amped up its sectarian Hindu

nationalism, unleashing an astonishing degree of violence against all those who

might not subscribe to this worldview, training its rhetoric and weaponry

against anyone who might be identified as “anti-national,” which includes all

those critical of Modi, the Hindu right, and Indian nationalism. In January

2015, immigration officials prevented a Greenpeace India staffer from boarding a flight to London, where she was scheduled

to speak to British members of parliament about the environmental risk of a proposed mine in Madhya

Pradesh, in central India, co-owned by a company listed on the London stock

exchange. The government also identified Greenpeace India as working against

the national interest, canceling its license to receive funds from outside

India. Later that year, the writer Arundhati Roy was issued a criminal contempt notice by a Nagpur court, for an article she published in Outlook magazine about

G.N. Saibaba, a disabled political dissident confined to a wheelchair, who had

been awaiting trial for a year. Roy argued Saibaba should not be prevented from

getting bail if Bajrangi and Kodnani, convicted for their role in the 2002

massacres, could, and if Amit Shah, once charged with ordering extrajudicial

executions, functioned with impunity as president of the BJP “and the

right-hand man of Prime Minister Narendra Modi.”

Shortly afterward, Rohith

Vemula, a 26-year-old Ph.D. student at the University of Hyderabad who was a

Dalit, the most oppressed of India’s castes, committed suicide. Vemula had protested the BJP student

wing’s forcible disruption of the screening of a documentary on riots provoked

by the BJP as part of Modi’s prime ministerial campaign, and had been targeted

by the Hindu right. Described as anti-national by two ministers in Modi’s

cabinet, and barred by authorities at the University of Hyderabad from entering

its hostels and public spaces, a practice reminiscent of the ostracization of

Dalits by upper-caste Hindus, he hanged himself.

In February, Kanhaiya Kumar, a

student leader at Jawaharlal Nehru University, a public university in Delhi

portrayed as an elite left bastion by the Hindu right, was arrested by the Delhi police on the orders of a BJP

minister for sedition. During two of Kumar’s court appearances,

lawyers (or men who claimed to be lawyers) assaulted students and faculty who had come to show their

solidarity with Kumar. For good measure, they also beat up journalists who

attempted to record the violence.

As in the 2002 massacres and

their aftermath, the degree of violence under Modi’s rule differs depending on

the target. In the case of Mohammad Akhlaq, a Muslim man lynched in September

on the suspicion of eating beef, it was a mob at the door with

swords and pistols. When a group of writers returned the national awards

they had received in protest of the Modi government’s sectarianism, a Bollywood

actor led a march against these writers for having “hurt the

spirit of India,” ending with a much-publicized meeting with Modi.

Against this backdrop, with

violence piling up almost faster than can be recorded, Modi has functioned as a

talking mask. Despite his ubiquity on social media, with two Twitter feeds, one

personal and one official, and despite being constantly photographed in

expensive clothes—he wore a reportedly $16,000 suit made on Savile Row when meeting Obama in Delhi

last January, a gift to him from a businessman, which was auctioned off

later—he is perhaps the most closed-off head of state India has seen. He rarely

gives interviews to the media, and never to journalists who might be critical

of him. But he is always making pronouncements, sometimes providing free internet for rural India with the assistance

of Mark Zuckerberg, sometimes solving climate change for the world in a Twitter

conversation with @potus, tweeting an endless stream of banalities.

A makeshift

barricade erected by Muslims in Gujarat to protect against Hindu attackers

during the 2002 rioting.Photograph

by Ami Vitale/Getty

His performance is a banal

kind of greatness, calibrated finely over a decade, even as behind and around

him violence moves in ranks that make it hard to tell the difference between

the mob and the police. Yet the authoritarian personality of Modi would be

without impact, without significance, if it did not resonate with the millions of authoritarian personalities among the

professionalized classes in India and the diaspora, in Silicon Valley, and New

Jersey, and Mumbai, and Delhi, among those who have risen so suddenly as to be

suffering from vertigo, who feel liberated from all meaningful knowledge,

whether from the past or the present, and who feel enslaved by their

liberation. While they harness their souls to the standards of professional,

material, Westernized success, to the air conditioning that Modi mocks when on

the campaign trail, their insecurity and humiliation about the West makes them

extract sustenance from Modi’s utterances about Hindus having invented plastic

surgery.

Modi engineered a

vigilante-police state, one in which the righteous were punished and

perpetrators rewarded.

Modi cannot be held solely

responsible for such rage and despair, even if he amplifies it. His supporters,

at home and in the West, the West itself, which chooses to ignore the violence

in India, and a complaisant liberal intelligentsia, concerned more with its

career prospects than with standing up to Modi, have to share the

responsibility. There is also much continuity between Modi’s India and what

preceded it, including the way in which the Congress stood aside during the

2002 massacres and their aftermath, selectively exploiting the culpability of

Modi and his government but never genuinely interested in justice; nurturing

Hindu majoritarianism under the guise of nationalism; promoting the enrichment

of a select few.

From this hollowed-out form of

success, bereft of love, spirituality, and justice, meaning can only emerge

from banality and hatred. Modi’s contradictions and lies channel the confusions

of his supporters perfectly. In a manner reminiscent of the vanguards of

China’s Cultural Revolution or the nativists flocking to Donald Trump, they

accuse the old elites of holding back the nation and the culture from true

greatness. They attack those responsible for the ruined past, the uncertain future,

and the endless present. They assail the “anti-nationals” who stand in their

way, beating and molesting people while shouting, “Bharat Mata Ki Jai.” They demand people say it to prove

they are not traitors, emboldened by a meeting of the BJP in March, led by

Modi, that declared a refusal to use the slogan as tantamount to disrespecting the Indian constitution. They

hammer, with swords and guns and smartphones and double-digit growth, at the

doors of the beef-eaters, the environmentalists, the university students, the

feminists, the Dalits, the leftists, the dissenting writers, the skeptics, the

“anti-nationals”—anyone who will not declare, both fists clenched, “Bharat

Mata Ki Jai!” They have a rage that must burn itself out, and all that

stands between them and the ashes of their rage is the astonishing, amazing

phenomenon of a world that can still produce, from the crushed bottom layers of

Indian society, people who, with every bit of the dignity and courage they can

muster, resist the lure of their silent, lonely, aloof, admired, and unloved

leader.

Siddhartha Deb is a

contributing editor at the New Republic and the author of The

Beautiful and the Damned.

Source:

newrepublic