Sunday, February 05, 2017

Wednesday, January 18, 2017

Millions in his firing squad

The Best of Mike Royko

Editor's

note: The

Chicago Daily News published this column April 5, 1968, after the assassination

of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

FBI

agents are looking for the man who pulled the trigger and surely they will find

him.

But it

doesn't matter if they do or they don't. They can't catch everybody, and Martin

Luther King was executed by a firing squad that numbered in the millions.

They took

part, from all over the country, pouring words of hate into the ear of the

assassin.

The man

with the gun did what he was told. Millions of bigots, subtle and obvious, put

it in his hand and assured him he was doing the right thing.

It would

be easy to point at the Southern redneck and say he did it. But what of the

Northern disk-jockey-turned-commentator, with his slippery words of hate every

morning?

What

about the Northern mayor who steps all over every poverty program advancement,

thinking only of political expediency, until riots fester, whites react with

more hate and the gap between the races grows bigger?

Toss in

the congressman with the stupid arguments against busing. And the pathetic

women who turn out with eggs in their hands to throw at children.

Let us

not forget the law-and-order type politicians who are in favor of arresting all

Negro prostitutes in the vice districts. When you ask them to vote for laws

that would eliminate some of the causes of prostitution, they babble like the

boobs they are.

Throw in

a Steve Telow or two: the Eastern and Southern European immigrant or his kid

who seems to be convinced that in 40 or 50 years he built this country. There

was nothing here until he arrived, you see, so that gives him the right to

pitch rocks when Martin Luther King walks down the street in his neighborhood.

They all

took their place in King's firing squad.

And

behind them were the subtle ones, those who never say anything bad but just nod

when the bigot throws out his strong opinions.

He is

actually the worst, the nodder is, because sometimes he believes differently

but he says nothing. He doesn't want to cause trouble. For Pete's sake, don't

cause trouble!

So when

his brother-in-law or his card-playing buddy from across the alley spews out

the racial filth, he nods.

Give some

credit to the most subtle of the subtle. That distinction belongs to the FBI,

now looking for King's killer.

That

agency took part in a mudslinging campaign against him that to this day demands

an investigation.

The

bullet that hit King came from all directions. Every two-bit politician or

incompetent editorial writer found in him, not themselves, the cause of our

racial problems.

It was

almost ludicrous. The man came on the American scene preaching nonviolence from

the first day he sat at the wrong end of a bus. He preached it in the North and

was hit with rocks. He talked it the day he was murdered.

Hypocrites

all over this country would kneel every Sunday morning and mouth messages to

Jesus Christ. Then they would come out and tell each other, after reading the

papers, that somebody should string up King, who was living Christianity like

few Americans ever have.

Maybe it

was the simplicity of his goal that confused people or the way he dramatized

it.

He wanted

only that black Americans have their constitutional rights,that they get an

equal shot at this country's benefits, the same thing we give to the last guy

who jumped off the boat.

So we

killed him. Just as we killed Abraham Lincoln and John F. Kennedy. No other

country kills so many of its best people.

Last

Sunday night the President said he was quitting after this term. He said this

country is so filled with hate it might help if he got out. Four days later we

killed a Nobel Peace Prize winner.

We have

pointed a gun at our own head and we are squeezing the trigger. And nobody we

elect is going to help us. It is our head and our finger.

© 1997

Chicago Tribune

Thursday, January 05, 2017

Saturday, December 17, 2016

Mark Rylance 'still holds conversations with his late stepdaughter'

Mark Rylance, the actor, has spoken for the first time about the

sudden death of his stepdaughter, saying he still has conversations with

her but the “explosion” of grief has affected his memory.

Actor Mark Rylance and his late stepdaughter Nataasha van Kampen Photo: Rex Features/Facebook

By Hannah Furness

1:20PM GMT 06 Jan 2013

Rylance, who dropped out of the London 2012 Olympic opening ceremony following the death of 28-year-old Nataasha van Kampen, said he believes her soul is “still existing somewhere in the universe”.

Speaking for the first time since her death, he disclosed he has held conversations with his stepdaughter “a lot of times”, with his imagination often allowing her to “do or say something that is very, very resonant”.

Rylance, who is currently starring in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night at the Globe, added the sudden loss had helped inform his portrayal of Olivia, who was also in mourning for close relatives.

Nataasha van Kampen, a film-maker, died suddenly on July 1 last year after suffering a brain haemorrhage on board a flight from New York to London. Her mother Claire has been married to Rylance for 20 years.

At the time, the actor felt compelled to withdraw from his performance at Danny Boyle’s Olympics opening ceremony, where he was expected to recite verses from The Tempest.

He has since continued with scheduled work in productions Richard III and Twelfth Night at Shakespeare’s Globe and in the West End.

In an interview with The Sunday Times, he has now spoken of his stepdaughter’s passing, and disclosed the “explosion” of her death made it difficult to see “what was going on before”.

Speaking of his beliefs, he told the newspaper: “That ability to tell when your imagination is receiving something and your imagination is creating something - that's a very subtle difference.

"I'm aware since Natasha's died of conversations with her, which obviously I have a lot of times. I'm aware sometimes in those of when I'm making up the conversation and sometimes I'll have a sense of, 'Oh, why did you say that?'

"In my imagination she'll do or say something that is very, very resonant, so I will feel from that my faith that her soul is still existing somewhere in the universe will be confirmed. Then I'll be doubtful that that's what I want it to be.

"So I swing between doubts and confidence."

He added the loss has affected his performance as Olivia in Twelfth Night, giving him a more “concrete experience” of mourning.

"One's life has changed, so one brings a different thing to it,” he said.

"Most obviously, more people have died that are close to me in the last 10 years, and so the fact that [Olivia] is in mourning for her father and her brother, I have now a more concrete experience of what that is."

He noted the character is “a little bit further down the road than I am”, with him simply “carrying on” rather necessarily moving forward yet.

“Maybe the play has turned up to encourage me in that way," he added.

Speaking of the Olympic ceremony, in which passages from The Tempest were read by Sir Kenneth Branagh, he said Danny Boyle’s staging was “very hard for me to remember."

"I think the strength of the sensations when someone very close to you dies has an effect where you can't quite see through the explosion to what was going on before,” he said.

Actor Mark Rylance and his late stepdaughter Nataasha van Kampen Photo: Rex Features/Facebook

By Hannah Furness

1:20PM GMT 06 Jan 2013

Rylance, who dropped out of the London 2012 Olympic opening ceremony following the death of 28-year-old Nataasha van Kampen, said he believes her soul is “still existing somewhere in the universe”.

Speaking for the first time since her death, he disclosed he has held conversations with his stepdaughter “a lot of times”, with his imagination often allowing her to “do or say something that is very, very resonant”.

Rylance, who is currently starring in Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night at the Globe, added the sudden loss had helped inform his portrayal of Olivia, who was also in mourning for close relatives.

Nataasha van Kampen, a film-maker, died suddenly on July 1 last year after suffering a brain haemorrhage on board a flight from New York to London. Her mother Claire has been married to Rylance for 20 years.

At the time, the actor felt compelled to withdraw from his performance at Danny Boyle’s Olympics opening ceremony, where he was expected to recite verses from The Tempest.

He has since continued with scheduled work in productions Richard III and Twelfth Night at Shakespeare’s Globe and in the West End.

In an interview with The Sunday Times, he has now spoken of his stepdaughter’s passing, and disclosed the “explosion” of her death made it difficult to see “what was going on before”.

Speaking of his beliefs, he told the newspaper: “That ability to tell when your imagination is receiving something and your imagination is creating something - that's a very subtle difference.

"I'm aware since Natasha's died of conversations with her, which obviously I have a lot of times. I'm aware sometimes in those of when I'm making up the conversation and sometimes I'll have a sense of, 'Oh, why did you say that?'

"In my imagination she'll do or say something that is very, very resonant, so I will feel from that my faith that her soul is still existing somewhere in the universe will be confirmed. Then I'll be doubtful that that's what I want it to be.

"So I swing between doubts and confidence."

He added the loss has affected his performance as Olivia in Twelfth Night, giving him a more “concrete experience” of mourning.

"One's life has changed, so one brings a different thing to it,” he said.

"Most obviously, more people have died that are close to me in the last 10 years, and so the fact that [Olivia] is in mourning for her father and her brother, I have now a more concrete experience of what that is."

He noted the character is “a little bit further down the road than I am”, with him simply “carrying on” rather necessarily moving forward yet.

“Maybe the play has turned up to encourage me in that way," he added.

Speaking of the Olympic ceremony, in which passages from The Tempest were read by Sir Kenneth Branagh, he said Danny Boyle’s staging was “very hard for me to remember."

"I think the strength of the sensations when someone very close to you dies has an effect where you can't quite see through the explosion to what was going on before,” he said.

Source: telegraph

Monday, December 05, 2016

Wednesday, November 23, 2016

The Identity Politics of Whiteness

First Words

By LAILA LALAMI NOV. 21, 2016

Illustration by Javier Jaén

Three years ago, I read “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” to my daughter. She smiled as she heard about Huck’s mischief, his jokes, his dress-up games, but it was his relationship with the runaway slave Jim that intrigued her most. Huck and Jim travel together as Jim seeks his freedom; at times, Huck wrestles with his decision to help. In the end, Tom Sawyer concocts an elaborate scheme for Jim’s release.

When we finished the book, my daughter had a question: Why didn’t Tom just tell Jim the truth — that Miss Watson had already freed him in her will? She is not alone in asking; scholars have long debated this issue. One answer lies in white identity, which needs black identity in order to define itself, and therefore cannot exist without it.

“Identity” is a vexing word. It is racial or sexual or national or religious or all those things at once. Sometimes it is proudly claimed, other times hidden or denied. But the word is almost never applied to whiteness. Racial identity is taken to be exclusive to people of color: When we speak about race, it is in connection with African-Americans or Latinos or Asians or Native People or some other group that has been designated a minority. “White” is seen as the default, the absence of race. In school curriculums, one month is reserved for the study of black history, while the rest of the year is just plain history; people will tell you they are fans of black or Latin music, but few will claim they love white music.

This year’s election has disturbed that silence. The president-elect earned the votes of a majority of white people while running a campaign that explicitly and consistently appealed to white identity and anxiety. At the heart of this anxiety is white people’s increasing awareness that they will become a statistical minority in this country within a generation. The paradox is that they have no language to speak about their own identity. “White” is a category that has afforded them an evasion from race, rather than an opportunity to confront it.

In his campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump regularly tied America’s problems to others. Immigration must be reformed, he told us, to stop the rapists and drug dealers coming here from Mexico. Terrorism could be stopped by banning Muslims from entering the country. The big banks would not be held in check by his opponent, whose picture he tweeted alongside a Star of David. The only people that the president-elect never faulted for anything were whites. These people he spoke of not as an indistinguishable mass but as a multitude of individuals, victims of a system that was increasingly rigged against them.

A common refrain in the days after the election was “Not all his voters are racist.” But this will not do, because those voters chose a candidate who promised them relief from their problems at the expense of other races. They may claim innocence now, but it seems to me that when a leading chapter of the Ku Klux Klan announces plans to hold a victory parade for the president-elect, the time for innocence is long past.

Racism is a necessary explanation for what happened on Nov. 8, but it is not a sufficient one. Last February, when the subject of racial identity came up at the Democratic primary debate in Milwaukee, the moderator Gwen Ifill surprised many viewers by asking about white voters: “By the middle of this century, the nation is going to be majority nonwhite,” she said. “Our public schools are already there. If working-class white Americans are about to be outnumbered, are already underemployed in many cases, and one study found they are dying sooner, don’t they have a reason to be resentful?”

Hillary Clinton said she was concerned about every community, including white communities “where we are seeing an increase in alcoholism, addiction, earlier deaths.” She said she planned to revitalize what she called “coal country” and explore spending more in communities with persistent generational poverty. Senator Bernie Sanders took a different view: “We can talk about it as a racial issue,” he said. “But it is a general economic issue.” Workers of all races, he said, have been hurt by trade deals like Nafta. “We need to start paying attention to the needs of working families in this country.”

This resonated with me: I, too, come from the working class, and from the significant portion of it that is not white. Neither of my parents went to college. Still, they managed to put their children through school and buy a home — a life that, for many in the working class, is impossible now. Nine months after that debate, we have found out exactly how much attention we should have been paying such families. The same white working-class voters who re-elected Obama four years ago did not cast their ballots for Clinton this year. These voters suffer from economic disadvantages even as they enjoy racial advantages. But it is impossible for them to notice these racial advantages if they live in rural areas where everyone around them is white. What they perceive instead is the cruel sense of being forgotten by the political class and condescended to by the cultural one.

While poor white voters are being scrutinized now, less attention has been paid to voters who are white and rich. White voters flocked to Trump by a wide margin, and he won a majority of voters who earn more than $50,000 a year, despite their relative economic safety. A majority of white women chose him, too, even though more than a dozen women have accused him of sexual assault. No, the top issue that drove Trump’s voters to the polls was not the economy — more voters concerned about that went to Clinton. It was immigration, an issue on which we’ve abandoned serious debate and become engulfed in sensational stories about rapists crossing the southern border or the pending imposition of Shariah law in the Midwest.

If whiteness is no longer the default and is to be treated as an identity — even, soon, a “minority” — then perhaps it is time white people considered the disadvantages of being a race. The next time a white man bombs an abortion clinic or goes on a shooting rampage on a college campus, white people might have to be lectured on religious tolerance and called upon to denounce the violent extremists in their midst. The opioid epidemic in today’s white communities could be treated the way we once treated the crack epidemic in black ones — not as a failure of the government to take care of its people but as a failure of the race. The fact that this has not happened, nor is it likely to, only serves as evidence that white Americans can still escape race.

Much has been made about privilege in this election. I will readily admit to many privileges. I have employer-provided health care. I live in a nice suburb. I am not dependent on government benefits. But I am also an immigrant and a person of color and a Muslim. On the night of the election, I was away from my family. Speaking to them on the phone, I could hear the terror in my daughter’s voice as the returns came in. The next morning, her friends at school, most of them Asian or Jewish or Hispanic, were in tears. My daughter called on the phone. “He can’t make us leave, right?” she asked. “We’re citizens.”

My husband and I did our best to quiet her fears. No, we said. He cannot make us leave. But every time I have thought about this conversation — and I have thought about it dozens of times, in my sleepless nights since the election — I have felt less certain. For all the privileges I can pass on to my daughter, there is one I cannot: whiteness.

Laila Lalami is the author, most recently, of “The Moor’s Account,” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Source: nytimes

By LAILA LALAMI NOV. 21, 2016

Illustration by Javier Jaén

Three years ago, I read “Adventures of Huckleberry Finn” to my daughter. She smiled as she heard about Huck’s mischief, his jokes, his dress-up games, but it was his relationship with the runaway slave Jim that intrigued her most. Huck and Jim travel together as Jim seeks his freedom; at times, Huck wrestles with his decision to help. In the end, Tom Sawyer concocts an elaborate scheme for Jim’s release.

When we finished the book, my daughter had a question: Why didn’t Tom just tell Jim the truth — that Miss Watson had already freed him in her will? She is not alone in asking; scholars have long debated this issue. One answer lies in white identity, which needs black identity in order to define itself, and therefore cannot exist without it.

“Identity” is a vexing word. It is racial or sexual or national or religious or all those things at once. Sometimes it is proudly claimed, other times hidden or denied. But the word is almost never applied to whiteness. Racial identity is taken to be exclusive to people of color: When we speak about race, it is in connection with African-Americans or Latinos or Asians or Native People or some other group that has been designated a minority. “White” is seen as the default, the absence of race. In school curriculums, one month is reserved for the study of black history, while the rest of the year is just plain history; people will tell you they are fans of black or Latin music, but few will claim they love white music.

This year’s election has disturbed that silence. The president-elect earned the votes of a majority of white people while running a campaign that explicitly and consistently appealed to white identity and anxiety. At the heart of this anxiety is white people’s increasing awareness that they will become a statistical minority in this country within a generation. The paradox is that they have no language to speak about their own identity. “White” is a category that has afforded them an evasion from race, rather than an opportunity to confront it.

In his campaign for the presidency, Donald Trump regularly tied America’s problems to others. Immigration must be reformed, he told us, to stop the rapists and drug dealers coming here from Mexico. Terrorism could be stopped by banning Muslims from entering the country. The big banks would not be held in check by his opponent, whose picture he tweeted alongside a Star of David. The only people that the president-elect never faulted for anything were whites. These people he spoke of not as an indistinguishable mass but as a multitude of individuals, victims of a system that was increasingly rigged against them.

A common refrain in the days after the election was “Not all his voters are racist.” But this will not do, because those voters chose a candidate who promised them relief from their problems at the expense of other races. They may claim innocence now, but it seems to me that when a leading chapter of the Ku Klux Klan announces plans to hold a victory parade for the president-elect, the time for innocence is long past.

Racism is a necessary explanation for what happened on Nov. 8, but it is not a sufficient one. Last February, when the subject of racial identity came up at the Democratic primary debate in Milwaukee, the moderator Gwen Ifill surprised many viewers by asking about white voters: “By the middle of this century, the nation is going to be majority nonwhite,” she said. “Our public schools are already there. If working-class white Americans are about to be outnumbered, are already underemployed in many cases, and one study found they are dying sooner, don’t they have a reason to be resentful?”

Hillary Clinton said she was concerned about every community, including white communities “where we are seeing an increase in alcoholism, addiction, earlier deaths.” She said she planned to revitalize what she called “coal country” and explore spending more in communities with persistent generational poverty. Senator Bernie Sanders took a different view: “We can talk about it as a racial issue,” he said. “But it is a general economic issue.” Workers of all races, he said, have been hurt by trade deals like Nafta. “We need to start paying attention to the needs of working families in this country.”

This resonated with me: I, too, come from the working class, and from the significant portion of it that is not white. Neither of my parents went to college. Still, they managed to put their children through school and buy a home — a life that, for many in the working class, is impossible now. Nine months after that debate, we have found out exactly how much attention we should have been paying such families. The same white working-class voters who re-elected Obama four years ago did not cast their ballots for Clinton this year. These voters suffer from economic disadvantages even as they enjoy racial advantages. But it is impossible for them to notice these racial advantages if they live in rural areas where everyone around them is white. What they perceive instead is the cruel sense of being forgotten by the political class and condescended to by the cultural one.

While poor white voters are being scrutinized now, less attention has been paid to voters who are white and rich. White voters flocked to Trump by a wide margin, and he won a majority of voters who earn more than $50,000 a year, despite their relative economic safety. A majority of white women chose him, too, even though more than a dozen women have accused him of sexual assault. No, the top issue that drove Trump’s voters to the polls was not the economy — more voters concerned about that went to Clinton. It was immigration, an issue on which we’ve abandoned serious debate and become engulfed in sensational stories about rapists crossing the southern border or the pending imposition of Shariah law in the Midwest.

If whiteness is no longer the default and is to be treated as an identity — even, soon, a “minority” — then perhaps it is time white people considered the disadvantages of being a race. The next time a white man bombs an abortion clinic or goes on a shooting rampage on a college campus, white people might have to be lectured on religious tolerance and called upon to denounce the violent extremists in their midst. The opioid epidemic in today’s white communities could be treated the way we once treated the crack epidemic in black ones — not as a failure of the government to take care of its people but as a failure of the race. The fact that this has not happened, nor is it likely to, only serves as evidence that white Americans can still escape race.

Much has been made about privilege in this election. I will readily admit to many privileges. I have employer-provided health care. I live in a nice suburb. I am not dependent on government benefits. But I am also an immigrant and a person of color and a Muslim. On the night of the election, I was away from my family. Speaking to them on the phone, I could hear the terror in my daughter’s voice as the returns came in. The next morning, her friends at school, most of them Asian or Jewish or Hispanic, were in tears. My daughter called on the phone. “He can’t make us leave, right?” she asked. “We’re citizens.”

My husband and I did our best to quiet her fears. No, we said. He cannot make us leave. But every time I have thought about this conversation — and I have thought about it dozens of times, in my sleepless nights since the election — I have felt less certain. For all the privileges I can pass on to my daughter, there is one I cannot: whiteness.

Laila Lalami is the author, most recently, of “The Moor’s Account,” a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.

Source: nytimes

Treat contempt with contempt

Comment

Abhinav Chandrachud

November 24, 2016 00:02 IST

The Supreme Court recently created history by issuing a contempt notice against one of its own former judges, Justice Markandey Katju. After retiring from office, Justice Katju has been known for making some very controversial remarks on social media. He has said that “90 per cent of Indians are idiots”, that Gandhi was a British agent, and that Kashmir and Bihar should be offered to Pakistan as a “package deal”. More recently, he put up a post on Facebook in which he called a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court “one of the most corrupt judges in India”. Since then, Justice Katju has made insinuations — again on Facebook — against the Supreme Court judge who issued the contempt notice against him. Although there is a right to free speech in India, no person can say anything here which “scandalises the court”, i.e., which lowers a court’s dignity or shakes public confidence in the judiciary. However, Justice Katju’s remarks, unbalanced though they may be, offer an opportunity for the Supreme Court to reconsider whether “scurrilous abuse” of judges should attract summary punishment under Indian law.

Blaze of glory

India got its law on “scandalising the court” from England. One of the earliest such cases decided there was R v. Almon (1765). A publisher in Piccadilly, London, had printed a pamphlet which accused Chief Justice Mansfield of acting “officiously, arbitrarily, and illegally”. He was hauled up for contempt of court. Justice Wilmot held that courts would lose all their authority if people were told that “Judges at their Chambers make Orders or Rules corruptly”. The purpose of the law of contempt, said Justice Wilmot, was “to keep a blaze of glory” around judges.

However, the doctrine of scandalising the court was used very sparingly in England thereafter. In a case decided in 1968, Lord Denning said that contempt of court must not be used to protect the dignity of courts, because “[t]hat must rest on surer foundations”. In 1974, the Phillimore Committee wrote in its report that most scandalous attacks against judges were best ignored because they usually came from “disappointed litigants or their friends” and to initiate proceedings against them would “merely give them greater publicity”. In 2012, the Law Commission there found that though there was a lot of abusive material directed against English judges, particularly online, much of it was “too silly” to be taken seriously. It was also noted that judges had successfully used civil defamation laws, instead of contempt of court, to penalise wrongdoers. For example, in 1992, Justice Popplewell succeeded in a defamation suit which he filed against the Today newspaper which had insinuated that he had fallen asleep during a murder trial. Eventually, in 2013, England abolished the offence of scandalising the court altogether.

Likewise, courts in the U.S. do not have the power to punish anyone for scandalising the court. In Bridges v. California (1941), Justice Felix Frankfurter of the U.S. Supreme Court called the doctrine of “scandalising the court” an example of English “foolishness”. In another case, Justice William O. Douglas wrote that judges are supposed to be “men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate”, who should be able to shrug off contemptuous statements.

From Davar to Tarkunde

Scandalising the court was an offence in colonial India much in the same manner as it was in England at the time. For instance, in 1908, the Bombay High Court hauled up N.C. Kelkar, publisher of Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s English-language newspaper, The Mahratta, for contempt. At the time, Justice Dinsha Davar had sentenced Tilak to be transported to a prison in Burma for six years upon his conviction for sedition. A July 1908 article in the paper accused Justice Davar of dishonestly colluding with the government for securing Tilak’s conviction. The article referred to Davar as “a medical quack in a red robe (and)… an impudent glow-worm holding his torch to the Sun.” Chief Justice Basil Scott in his judgment said that the article had “(overstepped) the bounds of fair criticism” by indulging in “scurrilous abuse” of Justice Davar.

When the Constitution was enacted in independent India, contempt of court was made an exception to the right to free speech, with very little debate in the Constituent Assembly. Consequently, the enactment of the Constitution made virtually no difference to the law on scandalising the court. For instance, in the 1960s, a defamation suit had been filed by Krishnaraj Thackersey against the prominent Bombay tabloid, Blitz, in the Bombay High Court. The case was decided by Justice V.M. Tarkunde, who awarded damages of Rs.3 lakh to Thackersey. Soon thereafter, an article appeared in the periodical Mainstream which alleged that Justice Tarkunde’s close relatives had been given a large loan from Bank of India, in which Thackersey was a director, as a quid pro quo for the judgment. The article was not very direct in making this point, but it made insinuations and relied on innuendos. Finding this to be in contempt of court, in Perspective Publications v. State of Maharashtra, the Supreme Court held that “the obvious implications and insinuations” in the article “immediately create a strong prejudicial impact” in the minds of the readers “about the lack of honesty, integrity and impartiality” of Justice Tarkunde in deciding the libel suit.

It is not contempt of court for a person to say, as Justice Katju has, that a Supreme Court judge “does not know an elementary principle of law”. This is intemperate criticism, not “scurrilous abuse”. However, since Justice Katju has questioned the integrity of a Supreme Court judge as well, he could be held in contempt of court unless he is either able to prove that his allegations were true or he unconditionally apologises to the court. However, one wonders if it is now time for India to reconsider whether courts should have the power to summarily punish those who make such statements. Are Justice Katju’s comments not, as the U.K. Law Commission wrote in 2012, “too silly” to be taken seriously? Are Indian judges not, as Justice Douglas said, “men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate”? Contempt powers today are unnecessarily designed to try and maintain a good public image for the judiciary. However, muzzling trenchant criticisms against judges will not preserve public confidence in courts. A person’s faith or confidence in a court will, after all, depend on the work that the court does, not on what people are publicly allowed to say about it. In the words of Justice Frank Murphy of the U.S. Supreme Court, “Silence and a steady devotion to duty are the best answers to irresponsible criticism”.

Of course, courts must have powers to preserve the dignity and decorum of day-to-day proceedings. For example, if a person starts shouting slogans during an ongoing court proceeding, flings a shoe at a judge hearing a case, or calls him corrupt in open court, the judge must have the power to remove that person from court and to penalise him so as to prevent this from happening again. But wild, scurrilous abuse heaped on judges on blogs or social media websites are perhaps best left ignored.

Abhinav Chandrachud is an advocate at the Bombay High Court.

Source: thehindu

Abhinav Chandrachud

November 24, 2016 00:02 IST

IN

THE MIND: “Contempt powers today are unnecessarily designed to try and

maintain a good public image for the judiciary.” A view of the Supreme

Court of India building. Photo: V. Sudershan

The

notice against Justice Katju is an opportune moment for the Supreme

Court to reconsider if ‘scurrilous abuse’ of judges should attract

summary punishment

The Supreme Court recently created history by issuing a contempt notice against one of its own former judges, Justice Markandey Katju. After retiring from office, Justice Katju has been known for making some very controversial remarks on social media. He has said that “90 per cent of Indians are idiots”, that Gandhi was a British agent, and that Kashmir and Bihar should be offered to Pakistan as a “package deal”. More recently, he put up a post on Facebook in which he called a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court “one of the most corrupt judges in India”. Since then, Justice Katju has made insinuations — again on Facebook — against the Supreme Court judge who issued the contempt notice against him. Although there is a right to free speech in India, no person can say anything here which “scandalises the court”, i.e., which lowers a court’s dignity or shakes public confidence in the judiciary. However, Justice Katju’s remarks, unbalanced though they may be, offer an opportunity for the Supreme Court to reconsider whether “scurrilous abuse” of judges should attract summary punishment under Indian law.

Blaze of glory

India got its law on “scandalising the court” from England. One of the earliest such cases decided there was R v. Almon (1765). A publisher in Piccadilly, London, had printed a pamphlet which accused Chief Justice Mansfield of acting “officiously, arbitrarily, and illegally”. He was hauled up for contempt of court. Justice Wilmot held that courts would lose all their authority if people were told that “Judges at their Chambers make Orders or Rules corruptly”. The purpose of the law of contempt, said Justice Wilmot, was “to keep a blaze of glory” around judges.

However, the doctrine of scandalising the court was used very sparingly in England thereafter. In a case decided in 1968, Lord Denning said that contempt of court must not be used to protect the dignity of courts, because “[t]hat must rest on surer foundations”. In 1974, the Phillimore Committee wrote in its report that most scandalous attacks against judges were best ignored because they usually came from “disappointed litigants or their friends” and to initiate proceedings against them would “merely give them greater publicity”. In 2012, the Law Commission there found that though there was a lot of abusive material directed against English judges, particularly online, much of it was “too silly” to be taken seriously. It was also noted that judges had successfully used civil defamation laws, instead of contempt of court, to penalise wrongdoers. For example, in 1992, Justice Popplewell succeeded in a defamation suit which he filed against the Today newspaper which had insinuated that he had fallen asleep during a murder trial. Eventually, in 2013, England abolished the offence of scandalising the court altogether.

Likewise, courts in the U.S. do not have the power to punish anyone for scandalising the court. In Bridges v. California (1941), Justice Felix Frankfurter of the U.S. Supreme Court called the doctrine of “scandalising the court” an example of English “foolishness”. In another case, Justice William O. Douglas wrote that judges are supposed to be “men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate”, who should be able to shrug off contemptuous statements.

From Davar to Tarkunde

Scandalising the court was an offence in colonial India much in the same manner as it was in England at the time. For instance, in 1908, the Bombay High Court hauled up N.C. Kelkar, publisher of Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s English-language newspaper, The Mahratta, for contempt. At the time, Justice Dinsha Davar had sentenced Tilak to be transported to a prison in Burma for six years upon his conviction for sedition. A July 1908 article in the paper accused Justice Davar of dishonestly colluding with the government for securing Tilak’s conviction. The article referred to Davar as “a medical quack in a red robe (and)… an impudent glow-worm holding his torch to the Sun.” Chief Justice Basil Scott in his judgment said that the article had “(overstepped) the bounds of fair criticism” by indulging in “scurrilous abuse” of Justice Davar.

When the Constitution was enacted in independent India, contempt of court was made an exception to the right to free speech, with very little debate in the Constituent Assembly. Consequently, the enactment of the Constitution made virtually no difference to the law on scandalising the court. For instance, in the 1960s, a defamation suit had been filed by Krishnaraj Thackersey against the prominent Bombay tabloid, Blitz, in the Bombay High Court. The case was decided by Justice V.M. Tarkunde, who awarded damages of Rs.3 lakh to Thackersey. Soon thereafter, an article appeared in the periodical Mainstream which alleged that Justice Tarkunde’s close relatives had been given a large loan from Bank of India, in which Thackersey was a director, as a quid pro quo for the judgment. The article was not very direct in making this point, but it made insinuations and relied on innuendos. Finding this to be in contempt of court, in Perspective Publications v. State of Maharashtra, the Supreme Court held that “the obvious implications and insinuations” in the article “immediately create a strong prejudicial impact” in the minds of the readers “about the lack of honesty, integrity and impartiality” of Justice Tarkunde in deciding the libel suit.

It is not contempt of court for a person to say, as Justice Katju has, that a Supreme Court judge “does not know an elementary principle of law”. This is intemperate criticism, not “scurrilous abuse”. However, since Justice Katju has questioned the integrity of a Supreme Court judge as well, he could be held in contempt of court unless he is either able to prove that his allegations were true or he unconditionally apologises to the court. However, one wonders if it is now time for India to reconsider whether courts should have the power to summarily punish those who make such statements. Are Justice Katju’s comments not, as the U.K. Law Commission wrote in 2012, “too silly” to be taken seriously? Are Indian judges not, as Justice Douglas said, “men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate”? Contempt powers today are unnecessarily designed to try and maintain a good public image for the judiciary. However, muzzling trenchant criticisms against judges will not preserve public confidence in courts. A person’s faith or confidence in a court will, after all, depend on the work that the court does, not on what people are publicly allowed to say about it. In the words of Justice Frank Murphy of the U.S. Supreme Court, “Silence and a steady devotion to duty are the best answers to irresponsible criticism”.

Of course, courts must have powers to preserve the dignity and decorum of day-to-day proceedings. For example, if a person starts shouting slogans during an ongoing court proceeding, flings a shoe at a judge hearing a case, or calls him corrupt in open court, the judge must have the power to remove that person from court and to penalise him so as to prevent this from happening again. But wild, scurrilous abuse heaped on judges on blogs or social media websites are perhaps best left ignored.

Abhinav Chandrachud is an advocate at the Bombay High Court.

Source: thehindu

Wednesday, November 16, 2016

Wednesday, November 02, 2016

An abandoned ayah

26 October 2016

Imagine being abandoned at London’s King’s Cross railway station with just one pound in your pocket. In 1908, this is exactly what happened to an ayah who had travelled from India to Britain to look after a family’s children on the journey home. An India Office Records file reveals the details of this story which was told in last night’s Sky Arts programme ‘Treasures of the British Library’ featuring Meera Syal.

Many British people employed an ayah to look after their children on the long voyage from India to Britain. The ayahs were at the heart of the family during the voyage, and their employer was supposed to provide for their passage home. However it was not unusual for ayahs to be dismissed once in Britain and left to fend for themselves. There were many critics of this callous behaviour because ayahs often suffered poverty and poor living conditions. In the late nineteenth century, these concerns led to the founding of the Ayahs’ Home in East London. Such was the demand that it moved to larger premises in 1921. They could enjoy a safe place to stay in the company of other ayahs and Chinese amahs, with food and décor that was intended to make them feel at home.

Inside the Ayah's Home in East London from G Sims Living London (1904-06)

The ayah highlighted in the broadcast arrived in England from Bombay with a Mrs Catchpole in May 1908. Mrs Catchpole asked Thomas Cook and Son to find the ayah another employer returning to India. The ayah’s services were duly transferred to a Mrs Drummond and she journeyed to Scotland where she spent fifteen days with the family. On 24 June the Drummonds came to London to take passage to Bombay the following day on SS Arabia. The family left the ayah at King’s Cross Station, giving her £1.

The Ayahs’ Home in Hackney East London, London City Mission Magazine (1921) PP.1041.C

From King’s Cross, the ayah managed to find her way to the office of Thomas Cook at Ludgate Hill. She was advised to go to the Ayahs’ Home in King Edward Road, Hackney. The matron of the Home, Sarah Annie Dunn, wrote to the India Office on 16 July reporting the case. Although the Home did not take charge of destitute ayahs, it would not turn the woman away. Mrs Dunn questioned whether it was against the law for a native of India to be abandoned in such a manner.

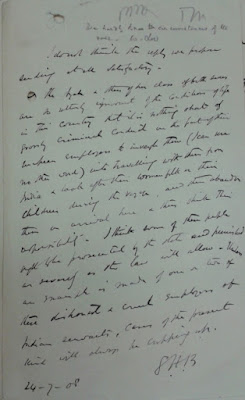

Sarah Annie Dunn’s letter 16 July 1908 IOR/L/PJ/6/881, File 2622 Noc

The India Office believed that the ayah had no legal remedy unless she had a written agreement that she would be taken back to India. The file notes that the India Office had declined to take responsibility in a previous case in 1890, and that the Government of India had then also refused to intervene. However Council of India member Syed Hussain Bilgrami recorded his disagreement with the proposed response, writing of ‘dishonest and cruel’ European employers inveigling Indian servants to travel with them and then abandoning them on arrival.

Syed Hussain Bilgrami’s dissenting minute 24 July 1908 IOR/L/PJ/6/881, File 2622 Noc

Nothing more is written in the file about the destitute woman. Perhaps she was one of the ayahs who developed a special expertise in looking after children on voyages and travelled regularly to Britain. But if it was her first voyage, then her experience of being abandoned must have been truly terrifying.

Penny Brook and Margaret Makepeace

India Office Records

Further reading:

Rozina Visram, Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History (Pluto Press, 2002)

Learning website: Asians in Britain

Making Britain

Judicial and Public Annual Files 2575-2672: Case of an ayah abandoned in London, 16 Jul 1908, IOR/L/PJ/6/881, File 2622 Explore Archives and Manuscripts

London City Mission Magazine, report on the opening of the Home of Nations (Ayahs’ Home) on 4 King Edward Road, Hackney in June 1921 (Dec 1921 issue, page 140) PP.10451.C

Imagine being abandoned at London’s King’s Cross railway station with just one pound in your pocket. In 1908, this is exactly what happened to an ayah who had travelled from India to Britain to look after a family’s children on the journey home. An India Office Records file reveals the details of this story which was told in last night’s Sky Arts programme ‘Treasures of the British Library’ featuring Meera Syal.

Many British people employed an ayah to look after their children on the long voyage from India to Britain. The ayahs were at the heart of the family during the voyage, and their employer was supposed to provide for their passage home. However it was not unusual for ayahs to be dismissed once in Britain and left to fend for themselves. There were many critics of this callous behaviour because ayahs often suffered poverty and poor living conditions. In the late nineteenth century, these concerns led to the founding of the Ayahs’ Home in East London. Such was the demand that it moved to larger premises in 1921. They could enjoy a safe place to stay in the company of other ayahs and Chinese amahs, with food and décor that was intended to make them feel at home.

Inside the Ayah's Home in East London from G Sims Living London (1904-06)

The Ayahs’ Home in Hackney East London, London City Mission Magazine (1921) PP.1041.C

From King’s Cross, the ayah managed to find her way to the office of Thomas Cook at Ludgate Hill. She was advised to go to the Ayahs’ Home in King Edward Road, Hackney. The matron of the Home, Sarah Annie Dunn, wrote to the India Office on 16 July reporting the case. Although the Home did not take charge of destitute ayahs, it would not turn the woman away. Mrs Dunn questioned whether it was against the law for a native of India to be abandoned in such a manner.

Sarah Annie Dunn’s letter 16 July 1908 IOR/L/PJ/6/881, File 2622 Noc

The India Office believed that the ayah had no legal remedy unless she had a written agreement that she would be taken back to India. The file notes that the India Office had declined to take responsibility in a previous case in 1890, and that the Government of India had then also refused to intervene. However Council of India member Syed Hussain Bilgrami recorded his disagreement with the proposed response, writing of ‘dishonest and cruel’ European employers inveigling Indian servants to travel with them and then abandoning them on arrival.

Syed Hussain Bilgrami’s dissenting minute 24 July 1908 IOR/L/PJ/6/881, File 2622 Noc

Nothing more is written in the file about the destitute woman. Perhaps she was one of the ayahs who developed a special expertise in looking after children on voyages and travelled regularly to Britain. But if it was her first voyage, then her experience of being abandoned must have been truly terrifying.

Penny Brook and Margaret Makepeace

India Office Records

Further reading:

Rozina Visram, Asians in Britain: 400 Years of History (Pluto Press, 2002)

Learning website: Asians in Britain

Making Britain

Judicial and Public Annual Files 2575-2672: Case of an ayah abandoned in London, 16 Jul 1908, IOR/L/PJ/6/881, File 2622 Explore Archives and Manuscripts

London City Mission Magazine, report on the opening of the Home of Nations (Ayahs’ Home) on 4 King Edward Road, Hackney in June 1921 (Dec 1921 issue, page 140) PP.10451.C

Source: Untold lives blog

Friday, October 28, 2016

Should the Indian State decide your religion for you?

Reservations debate

The Madras High Court refused a person's claim that he belonged to the Hindu Adi-Dravidar (Parayar) community.

8 hours ago Updated 6 hours ago

Shoaib Daniyal

In 1974, Pakistan’s parliament, led by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, passed a law decreeing that Ahmedis were to be known as a separate religious community with no link with Islam. Till then, under Pakistani law (and till now under Indian law), Ahmedis were seen as Muslim, given that that’s how they saw themselves. In the years since, Pakistan’s treatment of its Ahmedi minority has been a terrible record of discrimination.

Even though its clear that the state deciding people’s faith for them is a bad idea, this is what the Madras High Court did earlier this month. The court rejected the petitioner A Mutharasan’s contention that he belonged to Hindu Adi-Dravidar (Parayar) community because he was not able to produce any certificate of his parents or any of his relatives to show that he and his family members and his ancestors belonged to this community.

The court also rejected the petitioner's claim that he followed the Hindu faith, taking into account the fact that Mutharsan's "parents, sister and wife belong to Christianity and Bible and Bible versions were found in the house" and that he was:

"actively involved in all the activities and functions of the Church and also signed as a witness in a marriage celebrated in the Church. He was also in the Welcome Committee during the Anniversary Celebration of St. Paul Lutheran Church."

Reservations based on faith

Behind this peculiar instance of a court telling a person what his faith really is lies India’s system of affirmative action, which is based partly on religion. The case had come up before the High Court because the petitioner had been removed from his position as village headman by a local government body for allegedly converting to Christianity.

The religious stricture on reservations goes back to 1950, when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's government passed an order restricting the definition of “scheduled caste” only to people who profess the Hindu faith. In 1956, Nehru’s government included Sikhs in the definition, allowing them to also avail of quotas for seats in educational institutions and in government jobs. In 1990, the Union government bought Buddhists into the fold too. Conspicuously, there has been no sign of any political group – Congress or the Bharatiya Janata Party – wanting to bring in lower-caste Christians or Muslims into the “scheduled caste” reservation scheme.

Discriminating by religion

The logic for using a religious criteria to decide on India’s largest programme of affirmative action is strained. If the 1950 order, limiting reservation to Hindus, could be defended on the grounds that Hinduism is the only religion that has scriptural backing for a system of caste, that logic was blown out of the water by extending the Scheduled Caste umbrella to Sikhism and Buddhism – which, like Islam and Christianity, are egalitarian religions.

Moreover, the purpose of scheduled caste reservations is to help Dalits overcome millennia of caste oppression by savarnas or upper castes. How could a simple conversion to Islam or Christianity wipe out thousands of years of backwardness? How could a Dalit, no matter what his religion, compete with castes who have had no history of being oppressed?

The Indian state, it seems, has wildly overestimated the egalitarian powers of the two Abrahamic faiths. In fact, numerous ground studies have shown that even the worst features of the caste system survive across religious boundaries – including untouchability. For the Indian state to take crucial policy decisions on the basis of theology – rather than data – is a troubling sign.

Hindutva as state policy

Even more worrisome is the fact that the system of Dalit reservation as it now exists coincides almost perfectly with Vinayak Savarkar’s theocratic understanding of Indian society, which he mapped as per indigenous and non-indigenous faiths. Savarkar, one of the main political philosophers to define what Hindutva means, was clear that Muslims and Christians were to be given fewer rights given the foreign origin of these faiths.

Since India’s largest system of affirmative action is decided by religion – and excludes Muslims and Christians – the state’s move to now define people’s religious faith for them is an even more alarming development. The Ahmedis in Pakistan are proof of the slippery slope this sort of thinking could put the Indian Union on. Some governments in India, in fact, have already travelled some way down that slope. Five Indian states now all but ban religion conversions. Two of those – Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh – actually order anyone wanting to convert to first take permission from the state government. That Narendra Modi (then chief minister of Gujarat) or Madhya Pradesh’s Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan passed laws that allow bureaucrats to decide on someone’s personal faith is a sign that secularism as a concept is shakier in India than many would care to acknowledge.

We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.

The Madras High Court refused a person's claim that he belonged to the Hindu Adi-Dravidar (Parayar) community.

8 hours ago Updated 6 hours ago

Shoaib Daniyal

In 1974, Pakistan’s parliament, led by Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, passed a law decreeing that Ahmedis were to be known as a separate religious community with no link with Islam. Till then, under Pakistani law (and till now under Indian law), Ahmedis were seen as Muslim, given that that’s how they saw themselves. In the years since, Pakistan’s treatment of its Ahmedi minority has been a terrible record of discrimination.

Even though its clear that the state deciding people’s faith for them is a bad idea, this is what the Madras High Court did earlier this month. The court rejected the petitioner A Mutharasan’s contention that he belonged to Hindu Adi-Dravidar (Parayar) community because he was not able to produce any certificate of his parents or any of his relatives to show that he and his family members and his ancestors belonged to this community.

The court also rejected the petitioner's claim that he followed the Hindu faith, taking into account the fact that Mutharsan's "parents, sister and wife belong to Christianity and Bible and Bible versions were found in the house" and that he was:

"actively involved in all the activities and functions of the Church and also signed as a witness in a marriage celebrated in the Church. He was also in the Welcome Committee during the Anniversary Celebration of St. Paul Lutheran Church."

Reservations based on faith

Behind this peculiar instance of a court telling a person what his faith really is lies India’s system of affirmative action, which is based partly on religion. The case had come up before the High Court because the petitioner had been removed from his position as village headman by a local government body for allegedly converting to Christianity.

The religious stricture on reservations goes back to 1950, when Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru's government passed an order restricting the definition of “scheduled caste” only to people who profess the Hindu faith. In 1956, Nehru’s government included Sikhs in the definition, allowing them to also avail of quotas for seats in educational institutions and in government jobs. In 1990, the Union government bought Buddhists into the fold too. Conspicuously, there has been no sign of any political group – Congress or the Bharatiya Janata Party – wanting to bring in lower-caste Christians or Muslims into the “scheduled caste” reservation scheme.

Discriminating by religion

The logic for using a religious criteria to decide on India’s largest programme of affirmative action is strained. If the 1950 order, limiting reservation to Hindus, could be defended on the grounds that Hinduism is the only religion that has scriptural backing for a system of caste, that logic was blown out of the water by extending the Scheduled Caste umbrella to Sikhism and Buddhism – which, like Islam and Christianity, are egalitarian religions.

Moreover, the purpose of scheduled caste reservations is to help Dalits overcome millennia of caste oppression by savarnas or upper castes. How could a simple conversion to Islam or Christianity wipe out thousands of years of backwardness? How could a Dalit, no matter what his religion, compete with castes who have had no history of being oppressed?

The Indian state, it seems, has wildly overestimated the egalitarian powers of the two Abrahamic faiths. In fact, numerous ground studies have shown that even the worst features of the caste system survive across religious boundaries – including untouchability. For the Indian state to take crucial policy decisions on the basis of theology – rather than data – is a troubling sign.

Hindutva as state policy

Even more worrisome is the fact that the system of Dalit reservation as it now exists coincides almost perfectly with Vinayak Savarkar’s theocratic understanding of Indian society, which he mapped as per indigenous and non-indigenous faiths. Savarkar, one of the main political philosophers to define what Hindutva means, was clear that Muslims and Christians were to be given fewer rights given the foreign origin of these faiths.

Since India’s largest system of affirmative action is decided by religion – and excludes Muslims and Christians – the state’s move to now define people’s religious faith for them is an even more alarming development. The Ahmedis in Pakistan are proof of the slippery slope this sort of thinking could put the Indian Union on. Some governments in India, in fact, have already travelled some way down that slope. Five Indian states now all but ban religion conversions. Two of those – Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh – actually order anyone wanting to convert to first take permission from the state government. That Narendra Modi (then chief minister of Gujarat) or Madhya Pradesh’s Chief Minister Shivraj Singh Chauhan passed laws that allow bureaucrats to decide on someone’s personal faith is a sign that secularism as a concept is shakier in India than many would care to acknowledge.

We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.

Source: scrollin

Thursday, October 27, 2016

The way ahead

economist.com

Free

exchange | Oct 27th, 18:17

WHEREVER

I go these days, at home or abroad, people ask me the same question: what is

happening in the American political system? How has a country that has

benefited—perhaps more than any other—from immigration, trade and technological

innovation suddenly developed a strain of anti-immigrant, anti-innovation

protectionism? Why have some on the far left and even more on the far right

embraced a crude populism that promises a return to a past that is not possible

to restore—and that, for most Americans, never existed at all?

It’s true

that a certain anxiety over the forces of globalisation, immigration,

technology, even change itself, has taken hold in America. It’s not new, nor is

it dissimilar to a discontent spreading throughout the world, often manifested

in scepticism towards international institutions, trade agreements and

immigration. It can be seen in Britain’s recent vote to leave the European

Union and the rise of populist parties around the world.

Much of

this discontent is driven by fears that are not fundamentally economic. The

anti-immigrant, anti-Mexican, anti-Muslim and anti-refugee sentiment expressed

by some Americans today echoes nativist lurches of the past—the Alien and

Sedition Acts of 1798, the Know-Nothings of the mid-1800s, the anti-Asian

sentiment in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and any number of eras in

which Americans were told they could restore past glory if they just got some

group or idea that was threatening America under control. We overcame those

fears and we will again.

But some

of the discontent is rooted in legitimate concerns about long-term economic

forces. Decades of declining productivity growth and rising inequality have

resulted in slower income growth for low- and middle-income families.

Globalisation and automation have weakened the position of workers and their

ability to secure a decent wage. Too many potential physicists and engineers

spend their careers shifting money around in the financial sector, instead of

applying their talents to innovating in the real economy. And the financial

crisis of 2008 only seemed to increase the isolation of corporations and

elites, who often seem to live by a different set of rules to ordinary

citizens.

So it’s

no wonder that so many are receptive to the argument that the game is rigged.

But amid this understandable frustration, much of it fanned by politicians who would

actually make the problem worse rather than better, it is important to remember

that capitalism has been the greatest driver of prosperity and opportunity the

world has ever known.

Over the

past 25 years, the proportion of people living in extreme poverty has fallen

from nearly 40% to under 10%. Last year, American households enjoyed the

largest income gains on record and the poverty rate fell faster than at any

point since the 1960s. Wages have risen faster in real terms during this

business cycle than in any since the 1970s. These gains would have been

impossible without the globalisation and technological transformation that

drives some of the anxiety behind our current political debate.

This is

the paradox that defines our world today. The world is more prosperous than

ever before and yet our societies are marked by uncertainty and unease. So we

have a choice—retreat into old, closed-off economies or press forward,

acknowledging the inequality that can come with globalisation while committing

ourselves to making the global economy work better for all people, not just

those at the top.

A force

for good

The

profit motive can be a powerful force for the common good, driving businesses

to create products that consumers rave about or motivating banks to lend to

growing businesses. But, by itself, this will not lead to broadly shared

prosperity and growth. Economists have long recognised that markets, left to

their own devices, can fail. This can happen through the tendency towards

monopoly and rent-seeking that this newspaper has documented, the failure of

businesses to take into account the impact of their decisions on others through

pollution, the ways in which disparities of information can leave consumers

vulnerable to dangerous products or overly expensive health insurance.

More

fundamentally, a capitalism shaped by the few and unaccountable to the many is

a threat to all. Economies are more successful when we close the gap between

rich and poor and growth is broadly based. A world in which 1% of humanity

controls as much wealth as the other 99% will never be stable. Gaps between

rich and poor are not new but just as the child in a slum can see the

skyscraper nearby, technology allows anyone with a smartphone to see how the

most privileged live.

Expectations rise faster than governments can deliver and

a pervasive sense of injustice undermines peoples’ faith in the system. Without

trust, capitalism and markets cannot continue to deliver the gains they have

delivered in the past centuries.

This

paradox of progress and peril has been decades in the making. While I am proud

of what my administration has accomplished these past eight years, I have

always acknowledged that the work of perfecting our union would take far

longer. The presidency is a relay race, requiring each of us to do our part to

bring the country closer to its highest aspirations. So where does my successor

go from here?

Further

progress requires recognising that America’s economy is an enormously

complicated mechanism. As appealing as some more radical reforms can sound in

the abstract—breaking up all the biggest banks or erecting prohibitively steep

tariffs on imports—the economy is not an abstraction. It cannot simply be

redesigned wholesale and put back together again without real consequences for

real people.

Instead,

fully restoring faith in an economy where hardworking Americans can get ahead

requires addressing four major structural challenges: boosting productivity

growth, combating rising inequality, ensuring that everyone who wants a job can

get one and building a resilient economy that’s primed for future growth.

Restoring

economic dynamism

First, in

recent years, we have seen incredible technological advances through the

internet, mobile broadband and devices, artificial intelligence, robotics,

advanced materials, improvements in energy efficiency and personalised

medicine. But while these innovations have changed lives, they have not yet

substantially boosted measured productivity growth. Over the past decade,

America has enjoyed the fastest productivity growth in the G7, but it has

slowed across nearly all advanced economies (see chart 1). Without a

faster-growing economy, we will not be able to generate the wage gains people

want, regardless of how we divide up the pie.

A major

source of the recent productivity slowdown has been a shortfall of public and

private investment caused, in part, by a hangover from the financial crisis.

But it has also been caused by self-imposed constraints: an anti-tax ideology

that rejects virtually all sources of new public funding; a fixation on

deficits at the expense of the deferred maintenance bills we are passing to our

children, particularly for infrastructure; and a political system so partisan

that previously bipartisan ideas like bridge and airport upgrades are

nonstarters.

We could

also help private investment and innovation with business-tax reform that

lowers statutory rates and closes loopholes, and with public investments in

basic research and development. Policies focused on education are critical both

for increasing economic growth and for ensuring that it is shared broadly.

These include everything from boosting funding for early childhood education to

improving high schools, making college more affordable and expanding

high-quality job training.

Lifting

productivity and wages also depends on creating a global race to the top in

rules for trade. While some communities have suffered from foreign competition,

trade has helped our economy much more than it has hurt. Exports helped lead us

out of the recession. American firms that export pay their workers up to 18%

more on average than companies that do not, according to a report by my Council

of Economic Advisers. So, I will keep pushing for Congress to pass the

Trans-Pacific Partnership and to conclude a Transatlantic Trade and Investment

Partnership with the EU. These agreements, and stepped-up trade enforcement,

will level the playing field for workers and businesses alike.

Second,

alongside slowing productivity, inequality has risen in most advanced

economies, with that increase most pronounced in the United States. In 1979,

the top 1% of American families received 7% of all after-tax income. By 2007,

that share had more than doubled to 17%. This challenges the very essence of

who Americans are as a people. We don’t begrudge success, we aspire to it and

admire those who achieve it. In fact, we’ve often accepted more inequality than

many other nations because we are convinced that with hard work, we can improve

our own station and watch our children do even better.

As

Abraham Lincoln said, “while we do not propose any war upon capital, we do wish

to allow the humblest man an equal chance to get rich with everybody else.”

That’s the problem with increased inequality—it diminishes upward mobility. It

makes the top and bottom rungs of the ladder “stickier”—harder to move up and

harder to lose your place at the top.

Economists

have listed many causes for the rise of inequality: technology, education,

globalisation, declining unions and a falling minimum wage. There is something

to all of these and we’ve made real progress on all these fronts. But I believe

that changes in culture and values have also played a major role. In the past,

differences in pay between corporate executives and their workers were

constrained by a greater degree of social interaction between employees at all

levels—at church, at their children’s schools, in civic organisations. That’s

why CEOs took home about 20- to 30-times as much as their average worker. The

reduction or elimination of this constraining factor is one reason why today’s

CEO is now paid over 250-times more.

Economies

are more successful when we close the gap between rich and poor and growth is

broadly based. This is not just a moral argument. Research shows that growth is

more fragile and recessions more frequent in countries with greater inequality.

Concentrated wealth at the top means less of the broad-based consumer spending

that drives market economies.

America

has shown that progress is possible. Last year, income gains were larger for

households at the bottom and middle of the income distribution than for those

at the top (see chart 2). Under my administration, we will have boosted incomes

for families in the bottom fifth of the income distribution by 18% by 2017,

while raising the average tax rates on households projected to earn over $8m

per year—the top 0.1%—by nearly 7 percentage points, based on calculations by

the Department of the Treasury. While the top 1% of households now pay more of

their fair share, tax changes enacted during my administration have increased

the share of income received by all other families by more than the tax changes

in any previous administration since at least 1960.

Even these

efforts fall well short. In the future, we need to be even more aggressive in

enacting measures to reverse the decades-long rise in inequality. Unions should

play a critical role. They help workers get a bigger slice of the pie but they

need to be flexible enough to adapt to global competition. Raising the Federal

minimum wage, expanding the Earned Income Tax Credit for workers without

dependent children, limiting tax breaks for high-income households, preventing

colleges from pricing out hardworking students, and ensuring men and women get

equal pay for equal work would help to move us in the right direction too.

Third, a

successful economy also depends on meaningful opportunities for work for

everyone who wants a job. However, America has faced a long-term decline in

participation among prime-age workers (see chart 3). In 1953, just 3% of men

between 25 and 54 years old were out of the labour force. Today, it is 12%. In

1999, 23% of prime-age women were out of the labour force. Today, it is 26%.

People joining or rejoining the workforce in a strengthening economy have

offset ageing and retiring baby-boomers since the end of 2013, stabilising the

participation rate but not reversing the longer-term adverse trend.

Involuntary

joblessness takes a toll on life satisfaction, self-esteem, physical health and

mortality. It is related to a devastating rise of opioid abuse and an

associated increase in overdose deaths and suicides among non-college-educated

Americans—the group where labour-force participation has fallen most

precipitously.

There are

many ways to keep more Americans in the labour market when they fall on hard

times. These include providing wage insurance for workers who cannot get a new

job that pays as much as their old one. Increasing access to high-quality

community colleges, proven job-training models and help finding new jobs would

assist. So would making unemployment insurance available to more workers. Paid

leave and guaranteed sick days, as well as greater access to high-quality child

care and early learning, would add flexibility for employees and employers.

Reforms to our criminal-justice system and improvements to re-entry into the

workforce that have won bipartisan support would also improve participation, if

enacted.

Building

a sturdier foundation

Finally,

the financial crisis painfully underscored the need for a more resilient

economy, one that grows sustainably without plundering the future at the

service of the present. There should no longer be any doubt that a free market

only thrives when there are rules to guard against systemic failure and ensure

fair competition.

Post-crisis

reforms to Wall Street have made our financial system more stable and

supportive of long-term growth, including more capital for American banks, less

reliance on short-term funding, and better oversight for a range of

institutions and markets. Big American financial institutions no longer get the

type of easier funding they got before—evidence that the market increasingly

understands that they are no longer “too big to fail”. And we created a

first-of-its-kind watchdog—the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—to hold

financial institutions accountable, so their customers get loans they can repay

with clear terms up-front.

But even

with all the progress, segments of the shadow banking system still present

vulnerabilities and the housing-finance system has not been reformed. That

should be an argument for building on what we have already done, not undoing

it. And those who should be rising in defence of further reform too often

ignore the progress we have made, instead choosing to condemn the system as a

whole. Americans should debate how best to build on these rules, but denying

that progress leaves us more vulnerable, not less so.

America

should also do more to prepare for negative shocks before they occur. With

today’s low interest rates, fiscal policy must play a bigger role in combating

future downturns; monetary policy should not bear the full burden of

stabilising our economy. Unfortunately, good economics can be overridden by bad

politics. My administration secured much more fiscal expansion than many

appreciated in recovering from our crisis—more than a dozen bills provided $1.4

trillion in economic support from 2009 to 2012—but fighting Congress for each

commonsense measure expended substantial energy. I did not get some of the

expansions I sought and Congress forced austerity on the economy prematurely by

threatening a historic debt default. My successors should not have to fight for

emergency measures in a time of need. Instead, support for the hardest-hit

families and the economy, like unemployment insurance, should rise

automatically.

Maintaining

fiscal discipline in good times to expand support for the economy when needed

and to meet our long-term obligations to our citizens is vital. Curbs to

entitlement growth that build on the Affordable Care Act’s progress in reducing

health-care costs and limiting tax breaks for the most fortunate can address

long-term fiscal challenges without sacrificing investments in growth and

opportunity.

Finally,

sustainable economic growth requires addressing climate change. Over the past

five years, the notion of a trade-off between increasing growth and reducing

emissions has been put to rest. America has cut energy-sector emissions by 6%,

even as our economy has grown by 11% (see chart 4). Progress in America also

helped catalyse the historic Paris climate agreement, which presents the best

opportunity to save the planet for future generations.

A hope

for the future

America’s

political system can be frustrating. Believe me, I know. But it has been the

source of more than two centuries of economic and social progress. The progress

of the past eight years should also give the world some measure of hope.

Despite all manner of division and discord, a second Great Depression was

prevented. The financial system was stabilised without costing taxpayers a dime

and the auto industry rescued. I enacted a larger and more front-loaded fiscal

stimulus than even President Roosevelt’s New Deal and oversaw the most