By Express News Service | Published: 12th September 2017 07:55 PM

Last Updated: 12th September 2017 08:01 PM

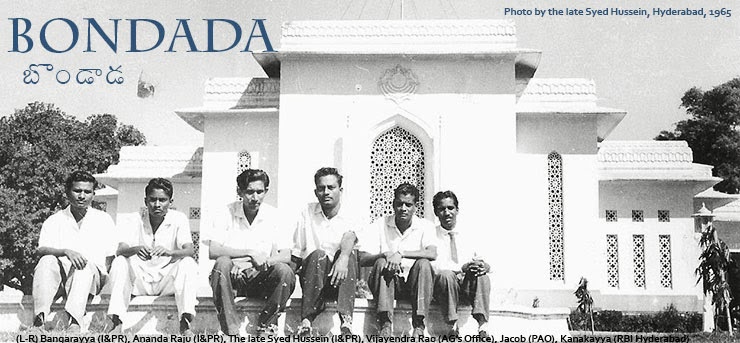

Social activist Medha Patkar and CPI(M) general secretary Sitaram Yechury at the Gauri Lankesh protest rally in Bangalore on Tuesday. (Nagesh Polali | EPS)

BENGALURU: Nothing can stop voices that speak out against the cowardice of those in power. This was the refrain at the #IamGauri protests attended by thousands of people in Bengaluru. The protests were held against attempts to silence free speech, presumably the reason why journalist Gauri Lankesh was shot dead in a murder that has similarities with that of literary scholar M M Kalburgi in Dharwad in 2015.

Speaking at the #IamGauri protests, Medha Patkar said, “Gauri Lankesh was not provocative in her articles. She spoke for Dalits, Adivasis and the backward. She spoke against anti-secular ideals. Some people are against those who speak out against the cowardice of those in power.”

“Gauri spoke out and they killed her. When Ramachandra Guha spoke out, they sent him a legal notice. Let them send 1.2 billion legal notices then. Where is Narendra Modi? Why hasn’t he spoken yet?” she demanded to know.

Rural journalist and farmers’ rights activist P Sainath warned that there will be incredible provocation in the days ahead and we should not fall into the trap of escalating hatred. He said, “They have a clear plan, ideology and coherent strategy. Look at it in different parts of the country, the strategy of violence has been different. In BJP-ruled states it is mob lynching and terror.”

“What you are up against is the largest constructed machine of hatred and intolerance ever seen since the partition of the country and perhaps greater than that since it has spread to so many more states and regions,” he said.

Chandrashekar Patil, better known as the writer ChamPa, read out a poem in memory of Gauri. “A few years ago, I was Dabholkar, then Pansare, and two years ago, when MM Kalburgi was assassinated, I became Kalburgi. Now, I’m Gauri,” he said.

CPM general secretary Sitaram Yechury said, “I’m a foot soldier of the Indian democracy and the idea of India. The idea of India is not abstract. It is concrete and the diversity of India along with the opportunity to speak, disagree and dissent is what makes this country. Gauri never eliminated ideas but the battle of ideas was fought with bullets.”

He said that Gauri had never disagreed violently, and she had always patiently listened to contrasting views, arguments and opinions. Though she disagreed only verbally, she was killed violently, he said.

“Those in power are creating a totalitarian state. We cannot be cowed down. It is the antithesis of India,” he said. He subtly pointed out Nathuram Godse’s association with RSS and said, “We should remember that Mahatma Gandhi was a victim of those who wanted a Hindu Rashtra.”

Prominent Kannada writer Devanur Mahadeva said we had forgotten the dreams that we had envisioned while getting independence. “Under Narendra Modi, our mentality is going backwards. The dream has become a nightmare. Kalburgi and Gauri are being killed as the majority goes forward.”

The protests, which started with a rally in the morning, went on till evening at Central College Grounds here.

Source: newindianexpress

Related Article: Massive crowds at #IamGauri protests in Bengaluru; Sitaram Yechury, Medha Patkar among prominent faces newindianexpress

Last Updated: 12th September 2017 08:01 PM

BENGALURU: Nothing can stop voices that speak out against the cowardice of those in power. This was the refrain at the #IamGauri protests attended by thousands of people in Bengaluru. The protests were held against attempts to silence free speech, presumably the reason why journalist Gauri Lankesh was shot dead in a murder that has similarities with that of literary scholar M M Kalburgi in Dharwad in 2015.

Speaking at the #IamGauri protests, Medha Patkar said, “Gauri Lankesh was not provocative in her articles. She spoke for Dalits, Adivasis and the backward. She spoke against anti-secular ideals. Some people are against those who speak out against the cowardice of those in power.”

“Gauri spoke out and they killed her. When Ramachandra Guha spoke out, they sent him a legal notice. Let them send 1.2 billion legal notices then. Where is Narendra Modi? Why hasn’t he spoken yet?” she demanded to know.

Rural journalist and farmers’ rights activist P Sainath warned that there will be incredible provocation in the days ahead and we should not fall into the trap of escalating hatred. He said, “They have a clear plan, ideology and coherent strategy. Look at it in different parts of the country, the strategy of violence has been different. In BJP-ruled states it is mob lynching and terror.”

“What you are up against is the largest constructed machine of hatred and intolerance ever seen since the partition of the country and perhaps greater than that since it has spread to so many more states and regions,” he said.

Chandrashekar Patil, better known as the writer ChamPa, read out a poem in memory of Gauri. “A few years ago, I was Dabholkar, then Pansare, and two years ago, when MM Kalburgi was assassinated, I became Kalburgi. Now, I’m Gauri,” he said.

CPM general secretary Sitaram Yechury said, “I’m a foot soldier of the Indian democracy and the idea of India. The idea of India is not abstract. It is concrete and the diversity of India along with the opportunity to speak, disagree and dissent is what makes this country. Gauri never eliminated ideas but the battle of ideas was fought with bullets.”

He said that Gauri had never disagreed violently, and she had always patiently listened to contrasting views, arguments and opinions. Though she disagreed only verbally, she was killed violently, he said.

“Those in power are creating a totalitarian state. We cannot be cowed down. It is the antithesis of India,” he said. He subtly pointed out Nathuram Godse’s association with RSS and said, “We should remember that Mahatma Gandhi was a victim of those who wanted a Hindu Rashtra.”

Prominent Kannada writer Devanur Mahadeva said we had forgotten the dreams that we had envisioned while getting independence. “Under Narendra Modi, our mentality is going backwards. The dream has become a nightmare. Kalburgi and Gauri are being killed as the majority goes forward.”

The protests, which started with a rally in the morning, went on till evening at Central College Grounds here.

Source: newindianexpress

Related Article: Massive crowds at #IamGauri protests in Bengaluru; Sitaram Yechury, Medha Patkar among prominent faces newindianexpress