Saturday, May 04, 2019

Friday, May 03, 2019

How would a razor know the difference between a boy and a girl?

In Partnership with #ShavingStereotypes

In the footsteps of ‘The Best A Man Can Be, Gillette’s latest ad makes a powerful statement

May 01, 2019

Long live, O son. Your birth brings fortune to the family, so begins Gillette’s latest ad in Banwari Tola, a small village in eastern Uttar Pradesh. The lyrics are derived from the Sohar, a traditional song sung in some parts of North India to celebrate the birth of a boy. The film begins with a little boy hopping and skipping around the village, taking in all the typical sights and scenes of a regular day in rural India. His father’s voice rings in his ears, “Children always learn from what they see.”

On his path, the child comes across vibrant scenes that define the way of life in his village — men roughing it out in the akhada, women returning after fetching water, men manning the shops around etc. He watches and learns, like a sponge that absorbs everything around it, and forms his own observations — the boys inherit their vocation from their father, while the girls have their domesticity to keep them occupied. It’s a fairly simple world he’s seen in his eight-year long life, until one day he notices something out of the ordinary during a trip to a barbershop.

Barbershops in India have always been all-male zones, so you can imagine the little boy’s bewilderment and absolute confusion when two girls pick up the razor.

“How would a razor know the difference between a boy and a girl?” Just one simple statement from the father to his son is enough to change his perspective forever. The film captures how deep-seated stereotypes can be shaved from the society. It’s through observation that gender norms get hard coded, and it’s through observation that they can also be dismantled.

Jyoti and Neha Narayan challenged the norms and ventured into a male-dominated profession by taking over their father’s barbershop at a very young age while ensuring not to skip their education . Seeing their sheer grit and determination, the entire village of Banwari Tola rallied behind them to help them in their endeavour. The girls now have a stream of loyal customers who appreciate their work and are their well-wishers. Jyoti and Neha have given the Sohar a new meaning in their village, long live O daughter, your birth brings light into our world.

The barbershop girls and the village of Banwari Tola have set an example for future generations on how to look beyond gender norms. Thanks to their efforts, the kids in their village will have no trouble imagining women as skilled barbers. After all, as the little boy’s father says in the closing scene of the ad, “Children always learn from what they see.”

By keeping it simple and yet #ShavingStereotypes, the Gillette ad beautifully brings out the story of two sisters who’re inspiring the next generation of men to rethink their notions about gender roles.

This article was produced by the Scroll marketing team on behalf of #ShavingStereotypes and not by the Scroll editorial team.

Source: scrollin

In the footsteps of ‘The Best A Man Can Be, Gillette’s latest ad makes a powerful statement

May 01, 2019

Long live, O son. Your birth brings fortune to the family, so begins Gillette’s latest ad in Banwari Tola, a small village in eastern Uttar Pradesh. The lyrics are derived from the Sohar, a traditional song sung in some parts of North India to celebrate the birth of a boy. The film begins with a little boy hopping and skipping around the village, taking in all the typical sights and scenes of a regular day in rural India. His father’s voice rings in his ears, “Children always learn from what they see.”

On his path, the child comes across vibrant scenes that define the way of life in his village — men roughing it out in the akhada, women returning after fetching water, men manning the shops around etc. He watches and learns, like a sponge that absorbs everything around it, and forms his own observations — the boys inherit their vocation from their father, while the girls have their domesticity to keep them occupied. It’s a fairly simple world he’s seen in his eight-year long life, until one day he notices something out of the ordinary during a trip to a barbershop.

Barbershops in India have always been all-male zones, so you can imagine the little boy’s bewilderment and absolute confusion when two girls pick up the razor.

“How would a razor know the difference between a boy and a girl?” Just one simple statement from the father to his son is enough to change his perspective forever. The film captures how deep-seated stereotypes can be shaved from the society. It’s through observation that gender norms get hard coded, and it’s through observation that they can also be dismantled.

Jyoti and Neha Narayan challenged the norms and ventured into a male-dominated profession by taking over their father’s barbershop at a very young age while ensuring not to skip their education . Seeing their sheer grit and determination, the entire village of Banwari Tola rallied behind them to help them in their endeavour. The girls now have a stream of loyal customers who appreciate their work and are their well-wishers. Jyoti and Neha have given the Sohar a new meaning in their village, long live O daughter, your birth brings light into our world.

The barbershop girls and the village of Banwari Tola have set an example for future generations on how to look beyond gender norms. Thanks to their efforts, the kids in their village will have no trouble imagining women as skilled barbers. After all, as the little boy’s father says in the closing scene of the ad, “Children always learn from what they see.”

By keeping it simple and yet #ShavingStereotypes, the Gillette ad beautifully brings out the story of two sisters who’re inspiring the next generation of men to rethink their notions about gender roles.

This article was produced by the Scroll marketing team on behalf of #ShavingStereotypes and not by the Scroll editorial team.

Source: scrollin

Friday, April 19, 2019

How Humayun convinced the love of his life to marry him

Valentine's Day

Hamida Bano grew up to be a feisty queen and loyal wife, but when she first met her husband, she was just an angry teen.

Rana Safvi Feb 14, 2017

Hamida Bano was a 14-year-old when Humayun Badshah, 33, met her in Pat, a town in Sehewan in the kingdom of Thatta, in 1541. Having been defeated by Sher Shah Suri in the battle of Kannauj, Humayun was on the run – he had lost the kingdom his father Babur had established in India and along with his half brother Hindal, he took refuge with Shah Hussain, the Sultan of Thatta in Sind.

After many days spent travelling through perilous and desolate deserts, they had finally found some peace. Humayun’s stepmother Dildar Bano, who was Hindal’s mother, gave a banquet in his honour and among the guests she invited, was the beautiful Hamida.

Hamida’s father Sheikh Ali Akbar, a Persian sufi more popularly known as Mir Baba Dost, was Hindal’s spiritual instructor, and there was a close bond between him and the family. As soon as Humayun saw Hamida Bano, he asked his stepmother Dildar, “Who is this?” He was mesmerised by the beauty and liveliness of the teenager and asked if she was already betrothed. On hearing that she was not, he expressed the desire to marry her.

Mirza Hindal was affronted. Not because, as some stories and texts say, he was in love with her – but because he was concerned about the family name.

“I look on this girl as a sister and child of my own,” he is believed to have said. “Your Majesty is a king – heaven forbid there should not be a proper meher, and so a cause of annoyance should rise.” Meher is a mandatory payment in the form of money or possessions paid or promised by the groom, or the groom’s father, to the bride at the time of marriage, which legally becomes her property. Hindal was concerned that an emperor on the run may not have enough resources for this endowment to his bride at the time of nikah, or their wedding.

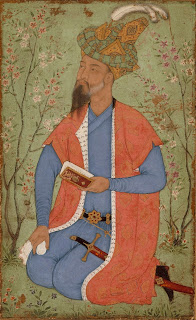

Emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Hindal Mirza, the younger half brother of the second Mughal emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Read more: scrollin

Hamida Bano grew up to be a feisty queen and loyal wife, but when she first met her husband, she was just an angry teen.

Rana Safvi Feb 14, 2017

Hamida Bano was a 14-year-old when Humayun Badshah, 33, met her in Pat, a town in Sehewan in the kingdom of Thatta, in 1541. Having been defeated by Sher Shah Suri in the battle of Kannauj, Humayun was on the run – he had lost the kingdom his father Babur had established in India and along with his half brother Hindal, he took refuge with Shah Hussain, the Sultan of Thatta in Sind.

After many days spent travelling through perilous and desolate deserts, they had finally found some peace. Humayun’s stepmother Dildar Bano, who was Hindal’s mother, gave a banquet in his honour and among the guests she invited, was the beautiful Hamida.

Hamida’s father Sheikh Ali Akbar, a Persian sufi more popularly known as Mir Baba Dost, was Hindal’s spiritual instructor, and there was a close bond between him and the family. As soon as Humayun saw Hamida Bano, he asked his stepmother Dildar, “Who is this?” He was mesmerised by the beauty and liveliness of the teenager and asked if she was already betrothed. On hearing that she was not, he expressed the desire to marry her.

Mirza Hindal was affronted. Not because, as some stories and texts say, he was in love with her – but because he was concerned about the family name.

“I look on this girl as a sister and child of my own,” he is believed to have said. “Your Majesty is a king – heaven forbid there should not be a proper meher, and so a cause of annoyance should rise.” Meher is a mandatory payment in the form of money or possessions paid or promised by the groom, or the groom’s father, to the bride at the time of marriage, which legally becomes her property. Hindal was concerned that an emperor on the run may not have enough resources for this endowment to his bride at the time of nikah, or their wedding.

Emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Hindal Mirza, the younger half brother of the second Mughal emperor Humayun. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Read more: scrollin

Monday, April 15, 2019

In highlighting India’s cultural diversity, an artist hopes to find her own identity

Internet Culture

Agrima Kaji’s illustration series ‘Beauty in Diversity’ spotlights cultural identifiers of Indian states through portraits of women in traditional attire.

Agrima Kaji

Damini Kulkarni

In an illustration by artist Agrima Kaji, a young woman can be seen holding her head high. Her pose, deftly detailed by the artist, radiates confidence and ease. She has wind in her hair and intricate tattoos on her body.

The illustration is among the 31 Kaji drew for her Beauty in Diversity project. Each features the profile of a woman dressed in traditional attire and depicts specific cultural identifiers associated with different Indian states. The images, shared on Kaji’s Instagram, are evocative and endearing celebrations of India’s cultural and ethnic diversity. But they also hint at the complexity of social and cultural mechanisms, which define collective identity.

Beauty in Diversity began with Kaji’s questions about her own identity. “My grandfather is from Himachal Pradesh, my mother is from Uttarakhand and my grandmother from Punjab,” said Kaji, who lives in Hyderabad. “And I am married into a Gujarati family. I have very diverse roots and I have always wondered what identity I should put forth as my own.”

Any attempt by Kaji “to define” herself became more difficult every time she moved cities. “I went from being a Delhiite to a Bangalorean and then a Hyderabadi,” said the 28-year-old, who is an alumna of the Delhi School of Art and National Institute of Design. Beauty in Diversity, then, was a means for Kaji “to find my own identity”.

Read full article: scrollin

Agrima Kaji’s illustration series ‘Beauty in Diversity’ spotlights cultural identifiers of Indian states through portraits of women in traditional attire.

Agrima Kaji

Damini Kulkarni

In an illustration by artist Agrima Kaji, a young woman can be seen holding her head high. Her pose, deftly detailed by the artist, radiates confidence and ease. She has wind in her hair and intricate tattoos on her body.

The illustration is among the 31 Kaji drew for her Beauty in Diversity project. Each features the profile of a woman dressed in traditional attire and depicts specific cultural identifiers associated with different Indian states. The images, shared on Kaji’s Instagram, are evocative and endearing celebrations of India’s cultural and ethnic diversity. But they also hint at the complexity of social and cultural mechanisms, which define collective identity.

Beauty in Diversity began with Kaji’s questions about her own identity. “My grandfather is from Himachal Pradesh, my mother is from Uttarakhand and my grandmother from Punjab,” said Kaji, who lives in Hyderabad. “And I am married into a Gujarati family. I have very diverse roots and I have always wondered what identity I should put forth as my own.”

Any attempt by Kaji “to define” herself became more difficult every time she moved cities. “I went from being a Delhiite to a Bangalorean and then a Hyderabadi,” said the 28-year-old, who is an alumna of the Delhi School of Art and National Institute of Design. Beauty in Diversity, then, was a means for Kaji “to find my own identity”.

Read full article: scrollin

As Pondicherry’s Creole food fades from restaurants, a Kannadiga home chef has become its evangelist

Food

In Motchamary Pushpam’s kitchen, it’s easy to see the diverse influences – French, Tamil, Portuguese, Dutch and Mughal – that shaped the region’s cusine.

Motchamary Pushpam | Priyadarshini Chatterjee

Priyadarshini Chatterjee

Sixty-eight-year-old Motchamary Pushpam, Pushpa to most, adjusted her apron and kept a pan on the flame. “Let’s fry the fish in the meantime,” she said in Tamil. On the adjacent flame, thinly sliced onions, garlic cloves, fresh curry leaves and a single bay leaf sizzled in another pan, releasing delightful aromas that wafted through her sunlit house.

Pushpa was busy making the quintessentially Pondicherrian Fish Assad Curry, a coconut-milk-laden curry, flavoured with anise and curry leaves and finished with a squeeze of lime. She would serve the dish at her table d’hôte lunch, later in the afternoon. “They have cut the fish a little too thin,” she complained, while grinding poppy seeds in an electric grinder. The poppy seed paste is an essential ingredient for the Assad Curry.

Anita de Canaga, Pushpa’s daughter, effortlessly repeated her mother’s words in French to the two French women, who had their attention and mobile cameras trained on Pushpa’s every move as she smoothly manoeuvred her way around her airy, uncluttered kitchen – chopping, blending and stirring, while the fish sizzled and crackled in the background. “My mother can speak some English and French, but she feels shy,” de Canaga explained. The conversation soon shifted to where to shop for white poppy seeds in Paris.

Pushpa’s reservation-only table d’hôte meals, which she hosts at her tastefully done home in a quiet, lush neighbourhood near the backwaters of Puducherry, are carefully curated to showcase the region’s own brand of Creole cuisine, which is fast disappearing from the city’s restaurants. The food is served on banana leaves and eating with hands is encouraged. Pushpa also offers cooking demonstrations, on request, at an additional charge.

Read full article: scrollin

In Motchamary Pushpam’s kitchen, it’s easy to see the diverse influences – French, Tamil, Portuguese, Dutch and Mughal – that shaped the region’s cusine.

Motchamary Pushpam | Priyadarshini Chatterjee

Priyadarshini Chatterjee

Sixty-eight-year-old Motchamary Pushpam, Pushpa to most, adjusted her apron and kept a pan on the flame. “Let’s fry the fish in the meantime,” she said in Tamil. On the adjacent flame, thinly sliced onions, garlic cloves, fresh curry leaves and a single bay leaf sizzled in another pan, releasing delightful aromas that wafted through her sunlit house.

Pushpa was busy making the quintessentially Pondicherrian Fish Assad Curry, a coconut-milk-laden curry, flavoured with anise and curry leaves and finished with a squeeze of lime. She would serve the dish at her table d’hôte lunch, later in the afternoon. “They have cut the fish a little too thin,” she complained, while grinding poppy seeds in an electric grinder. The poppy seed paste is an essential ingredient for the Assad Curry.

Anita de Canaga, Pushpa’s daughter, effortlessly repeated her mother’s words in French to the two French women, who had their attention and mobile cameras trained on Pushpa’s every move as she smoothly manoeuvred her way around her airy, uncluttered kitchen – chopping, blending and stirring, while the fish sizzled and crackled in the background. “My mother can speak some English and French, but she feels shy,” de Canaga explained. The conversation soon shifted to where to shop for white poppy seeds in Paris.

Pushpa’s reservation-only table d’hôte meals, which she hosts at her tastefully done home in a quiet, lush neighbourhood near the backwaters of Puducherry, are carefully curated to showcase the region’s own brand of Creole cuisine, which is fast disappearing from the city’s restaurants. The food is served on banana leaves and eating with hands is encouraged. Pushpa also offers cooking demonstrations, on request, at an additional charge.

Read full article: scrollin

Sunday, April 07, 2019

Thursday, March 21, 2019

What the United States can learn from the evolution of the Indian Constitution

Interpreting The Constitution

The histories of the US and Indian constitutions show two related political and legal systems evolving over time.

First day of Constituent Assembly of India. From Left: BG Kher and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. KM Munshi is seated behind Patel | Wikimedia Commons

Samir Chopra, Aeon

The United States and India, two of the world’s largest and oldest democracies, are both governed on the basis of written constitutions. One of the inspirations for the Constitution of India, drafted between 1947 and 1950, was the US Constitution. Both Indians and Americans revere their “constitutional rights” – especially the “fundamental right” of free speech, and the separation of state and religion. Both countries support critical traditions that focus on particular clauses of the constitution.

In India, Article 356, which allows for the suspension of state legislative assemblies to permit “direct rule by the Centre”, has provoked considerable critique, while in the US, the Second Amendment is a source of perpetual political and legal discord. The Indian and US supreme courts both enjoy the power of judicial review, to declare acts of other branches of government illegitimate, and so a measure of “supremacy” over their respective legislative branches. For this reason, both constitutions are “undemocratic” in their arrogation of too much political power to the judicial bench – a group of unelected public servants.

The US and Indian constitutions diverge in their stability or flexibility. The US Constitution is very difficult to change and, thanks to a religious American sensibility that treats it as a sacral document, it has simply not evolved, impervious to the changing needs of a growing and progressing nation and world. The Constitution of India suffers from the converse flaw; in less than 75 years, it has been amended, at last count, 103 times. This kind of recipe for political instability is precisely the worry cited by those who resist attempts to make it easier to amend the US Constitution.

Stability versus change

How flexible should constitutions be? How often, and how, should they change? Is a written constitution – unlike the unwritten British one – an invitation to the political polarities of instability or stasis? There is no simple answer to these questions. But history offers some guidance. Law, when it emerged in the great ancient Mesopotamian civilisations, was a “tool of government’” Such a demystified, pragmatic view of law suggests legal constitutions are technologies for governing, designed and implemented to bring about socially negotiated outcomes. Depending on the histories and needs of their “parent societies”, different kinds of constitutions come about, generating histories of political, legal and economic evolution, and being altered by them in turn. The histories of the US and Indian constitutions show two related political and legal systems evolving over time, their variations underwritten by their country’s historical experiences. The history of the Indian state and constitution includes a pragmatic American influence, with which the US would now benefit being reacquainted.

In 1947, Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote to a member of India’s drafting committee, Sir Benegal Narsing Rau, advising him to delete references to “the due process of law” from the working draft of the Constitution of India. Justice Frankfurter’s logic was simple. In the so-called “Lochner era” (1897-1937), the US Supreme Court, by utilising its power of judicial review, had often struck down social welfare legislation enacted by a busy US legislature. The legislature’s social welfare programmes were responses to the needs of an economically desperate polity; the court answered by reasserting the needs of the “business class” and the “haves”. Such antidemocratic inclinations were arrested only by the “switch in time that saved nine”. That was how Thomas Reed Powell of the Harvard Law School characterised the US Supreme Court’s reversal of its rulings in this domain in the face of President Franklin Roosevelt’s threat to place additional judges more sympathetic to his legislative initiatives on the Supreme Court. Politics, in other words, compelled a historic constitutional transformation.

Lessons from India

In 1947, as India looked ahead to its nascent republic status, its new Constituent Assembly planned extensive land reforms. These reforms sought to reduce the entrenched power of India’s landlords and bring relief to their serfs in India’s provinces; they would, at a minimum, involve some “seizures” or “takings” of landed property. An Indian landlord equipped with a copy of the American due process clause might expect to find the new Indian Supreme Court willing to stand by him and, as the US Supreme Court first tried to do with the New Deal, thwart the democratic reforms of the legislature. Such judicial intervention, likely in the name of “due process”, would threaten India’s post-independence progress toward the eventual realisation of a republic that ensured the wellbeing of all its citizens. The drafters of the Indian constitution paid heed to Frankfurter’s advice.

The first version of the due process clause in the Constitution of India had read: “Nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty and property without due process of law”. Soon, the word “property” was deleted. Moreover, to prevent the broad interpretation of “liberty” that the US Supreme Court had shown in Lochner v New York, when it had struck down minimum-wage legislation, “liberty” was qualified as “personal liberty” – not corporate. Lastly, to minimise the expressive impact of ‘due process of law’, that phrase was replaced by ‘procedure established by law’. Finally, Article 21 of the Constitution of India read: ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.’ India’s land reforms went through – partially – helping a newly independent democracy, the world’s largest, move beyond feudalism.

The US can learn something from this little history lesson. Every constitution offers a particular set of solutions to a social, economic and cultural context. India did not copy the US Constitution; it took what worked for it and no more. Moreover, if constitutions are tools for governance, then they simply must change over time, through trial and error. Constitutions should be changed as often as their subjects want to change them, to bring about the results they want for their political community. Thomas Jefferson suggested that every generation of Americans should draft its own version to meet the particularities of its time. Jefferson calculated, using actuarial tables, how often this should be: 19 years. Americans pride themselves on their pragmatic and innovative nature; that self-image should suggest that the all-American thing to do is to desacralise the US Constitution, remove it from the pulpit, and put it in its place, a toolbox of governance, there to be used and modified to – as the US framers of the constitution put it – “make a more perfect union”.

Article: scrollin

The histories of the US and Indian constitutions show two related political and legal systems evolving over time.

First day of Constituent Assembly of India. From Left: BG Kher and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel. KM Munshi is seated behind Patel | Wikimedia Commons

Samir Chopra, Aeon

The United States and India, two of the world’s largest and oldest democracies, are both governed on the basis of written constitutions. One of the inspirations for the Constitution of India, drafted between 1947 and 1950, was the US Constitution. Both Indians and Americans revere their “constitutional rights” – especially the “fundamental right” of free speech, and the separation of state and religion. Both countries support critical traditions that focus on particular clauses of the constitution.

In India, Article 356, which allows for the suspension of state legislative assemblies to permit “direct rule by the Centre”, has provoked considerable critique, while in the US, the Second Amendment is a source of perpetual political and legal discord. The Indian and US supreme courts both enjoy the power of judicial review, to declare acts of other branches of government illegitimate, and so a measure of “supremacy” over their respective legislative branches. For this reason, both constitutions are “undemocratic” in their arrogation of too much political power to the judicial bench – a group of unelected public servants.

The US and Indian constitutions diverge in their stability or flexibility. The US Constitution is very difficult to change and, thanks to a religious American sensibility that treats it as a sacral document, it has simply not evolved, impervious to the changing needs of a growing and progressing nation and world. The Constitution of India suffers from the converse flaw; in less than 75 years, it has been amended, at last count, 103 times. This kind of recipe for political instability is precisely the worry cited by those who resist attempts to make it easier to amend the US Constitution.

Stability versus change

How flexible should constitutions be? How often, and how, should they change? Is a written constitution – unlike the unwritten British one – an invitation to the political polarities of instability or stasis? There is no simple answer to these questions. But history offers some guidance. Law, when it emerged in the great ancient Mesopotamian civilisations, was a “tool of government’” Such a demystified, pragmatic view of law suggests legal constitutions are technologies for governing, designed and implemented to bring about socially negotiated outcomes. Depending on the histories and needs of their “parent societies”, different kinds of constitutions come about, generating histories of political, legal and economic evolution, and being altered by them in turn. The histories of the US and Indian constitutions show two related political and legal systems evolving over time, their variations underwritten by their country’s historical experiences. The history of the Indian state and constitution includes a pragmatic American influence, with which the US would now benefit being reacquainted.

In 1947, Justice Felix Frankfurter wrote to a member of India’s drafting committee, Sir Benegal Narsing Rau, advising him to delete references to “the due process of law” from the working draft of the Constitution of India. Justice Frankfurter’s logic was simple. In the so-called “Lochner era” (1897-1937), the US Supreme Court, by utilising its power of judicial review, had often struck down social welfare legislation enacted by a busy US legislature. The legislature’s social welfare programmes were responses to the needs of an economically desperate polity; the court answered by reasserting the needs of the “business class” and the “haves”. Such antidemocratic inclinations were arrested only by the “switch in time that saved nine”. That was how Thomas Reed Powell of the Harvard Law School characterised the US Supreme Court’s reversal of its rulings in this domain in the face of President Franklin Roosevelt’s threat to place additional judges more sympathetic to his legislative initiatives on the Supreme Court. Politics, in other words, compelled a historic constitutional transformation.

Lessons from India

In 1947, as India looked ahead to its nascent republic status, its new Constituent Assembly planned extensive land reforms. These reforms sought to reduce the entrenched power of India’s landlords and bring relief to their serfs in India’s provinces; they would, at a minimum, involve some “seizures” or “takings” of landed property. An Indian landlord equipped with a copy of the American due process clause might expect to find the new Indian Supreme Court willing to stand by him and, as the US Supreme Court first tried to do with the New Deal, thwart the democratic reforms of the legislature. Such judicial intervention, likely in the name of “due process”, would threaten India’s post-independence progress toward the eventual realisation of a republic that ensured the wellbeing of all its citizens. The drafters of the Indian constitution paid heed to Frankfurter’s advice.

The first version of the due process clause in the Constitution of India had read: “Nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty and property without due process of law”. Soon, the word “property” was deleted. Moreover, to prevent the broad interpretation of “liberty” that the US Supreme Court had shown in Lochner v New York, when it had struck down minimum-wage legislation, “liberty” was qualified as “personal liberty” – not corporate. Lastly, to minimise the expressive impact of ‘due process of law’, that phrase was replaced by ‘procedure established by law’. Finally, Article 21 of the Constitution of India read: ‘No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.’ India’s land reforms went through – partially – helping a newly independent democracy, the world’s largest, move beyond feudalism.

The US can learn something from this little history lesson. Every constitution offers a particular set of solutions to a social, economic and cultural context. India did not copy the US Constitution; it took what worked for it and no more. Moreover, if constitutions are tools for governance, then they simply must change over time, through trial and error. Constitutions should be changed as often as their subjects want to change them, to bring about the results they want for their political community. Thomas Jefferson suggested that every generation of Americans should draft its own version to meet the particularities of its time. Jefferson calculated, using actuarial tables, how often this should be: 19 years. Americans pride themselves on their pragmatic and innovative nature; that self-image should suggest that the all-American thing to do is to desacralise the US Constitution, remove it from the pulpit, and put it in its place, a toolbox of governance, there to be used and modified to – as the US framers of the constitution put it – “make a more perfect union”.

Article: scrollin

Wednesday, March 06, 2019

Thursday, February 28, 2019

The Modi Years: What has fuelled rising mob violence in India?

The Modi Years

The ruling party’s leaders have supported violence in the name of cow protection.

Design | Nithya Subramanian

Feb 23, 2019 · 07:30 pm

Shoaib Daniyal

The past five years of the Modi government have seen a spate of mob attacks across India. The elements that fuelled this bloody mix include religious fanaticism (specifically, cow protection), increased penetration of social media and politicians, who ranged from being apathetic to instigators of violence.

Dadri, 2015

......

Dadri is a small Uttar Pradesh town on the peri-urban edges of the National Capital Region. On September 28, 2015, villagers in Bisahra village close to Dadri, accused Mohammed Akhlaq of stealing and slaughtering a calf for Eid, which was three days ago. Later, an announcement was allegedly made from the local temple’s public address system to gather a mob, which then proceeded to Akhlaq’s house. Akhlaq and his son Danish were dragged out and beaten with rods and bricks. Their fridge was raided and a leftover meat curry was seen as proof that they had killed a cow (Akhlaq’s family insisted it was goat meat). Akhlaq died from the assault. Danish was severely injured and had to undergo brain surgery later. .......

Relatives of Mohammad Akhlaq mourn after he was killed by a mob in Dadri. Photo: Reuters

Unleashing a flood

Dadri set a template. Cow protection vigilantes would assault men they accused of either killings cows or transporting cattle to be slaughtered. Moreover, these would then not be treated as ordinary crimes. The vigilantes would often be supported, sometimes explicitly, by political parties and governments. In March 2016, two cattle traders were lynched and their bodies hung up from a tree in Jharkhand. In July 2016, four Dalit men were assaulted in Una, Gujarat for skinning dead cows and their assault filmed by the perpetrators themselves. .......

Beyond gau raksha

........

On June 27, 2017, a mentally ill woman was lynched in West Bengal after a 14-year old child went missing in the area with and rumours of Bangladeshi child abductors being active in the area. In June, 2018, a mob in Assam beat two young men to death – again on the suspicious on being child lifters. During the assault, the victims pleaded with the assaulters that they were Assamese – even listing their parents’ names but the mob did not listen. May 2018 saw multiple mob attacks in Andhra Pradesh of Hindi-speaking people as false rumours spread that child abductor gangs from Bihar and Jharkhand were active in the state. Two months later, five men from a nomadic tribe were beaten to death in Maharashtra.

Women mourn the loss of their relatives in a mob attack in Dhule. Phone: Shone Satheesh

Political reactions

......

Politically, the reaction to mob violence was either muted or in support of it. After the Bulandshahr killing, one BJP MLA argued that the policeman had actually shot himself and the rampaging mob had not role to play.

Prime Minister Modi had not said much on the violence in spite of the clear danger it represents. In 2017, he appealed for people to not take the law in their hands in case they suspect cow slaughter but allow the legal system to do its work (a large number of Indian states have made slaughtering cattle illegal). In 2019, Modi again condemned lynchings but also asked rhetorically if they began only in 2014.

So strong is the force of the mob that even the Opposition has been muted on the issue. The Congress has said little on how it intends to tackle lynchings and neither have any of the other parties in North and West India even as the general elections approach.

The only movement on the issue has been from WhatsApp, by far India’s most popular mobile phone messaging service. In July, 2018, the company limited forwarding of messaged to five chats at a time in a bid to curb rumours.

Read full article: scrollin

The ruling party’s leaders have supported violence in the name of cow protection.

Design | Nithya Subramanian

Feb 23, 2019 · 07:30 pm

Shoaib Daniyal

- The past five years have seen mob lynchings across India

- Factors driving violence include cow protection movements and penetration of social media

- The effects are significant with a near-collapse of the rural cattle trade and worsening law and order

- In spite of the threat to law and order, political reaction has either been muted or has supported vigilante action

The past five years of the Modi government have seen a spate of mob attacks across India. The elements that fuelled this bloody mix include religious fanaticism (specifically, cow protection), increased penetration of social media and politicians, who ranged from being apathetic to instigators of violence.

Dadri, 2015

......

Dadri is a small Uttar Pradesh town on the peri-urban edges of the National Capital Region. On September 28, 2015, villagers in Bisahra village close to Dadri, accused Mohammed Akhlaq of stealing and slaughtering a calf for Eid, which was three days ago. Later, an announcement was allegedly made from the local temple’s public address system to gather a mob, which then proceeded to Akhlaq’s house. Akhlaq and his son Danish were dragged out and beaten with rods and bricks. Their fridge was raided and a leftover meat curry was seen as proof that they had killed a cow (Akhlaq’s family insisted it was goat meat). Akhlaq died from the assault. Danish was severely injured and had to undergo brain surgery later. .......

Relatives of Mohammad Akhlaq mourn after he was killed by a mob in Dadri. Photo: Reuters

Unleashing a flood

Dadri set a template. Cow protection vigilantes would assault men they accused of either killings cows or transporting cattle to be slaughtered. Moreover, these would then not be treated as ordinary crimes. The vigilantes would often be supported, sometimes explicitly, by political parties and governments. In March 2016, two cattle traders were lynched and their bodies hung up from a tree in Jharkhand. In July 2016, four Dalit men were assaulted in Una, Gujarat for skinning dead cows and their assault filmed by the perpetrators themselves. .......

Beyond gau raksha

........

On June 27, 2017, a mentally ill woman was lynched in West Bengal after a 14-year old child went missing in the area with and rumours of Bangladeshi child abductors being active in the area. In June, 2018, a mob in Assam beat two young men to death – again on the suspicious on being child lifters. During the assault, the victims pleaded with the assaulters that they were Assamese – even listing their parents’ names but the mob did not listen. May 2018 saw multiple mob attacks in Andhra Pradesh of Hindi-speaking people as false rumours spread that child abductor gangs from Bihar and Jharkhand were active in the state. Two months later, five men from a nomadic tribe were beaten to death in Maharashtra.

Women mourn the loss of their relatives in a mob attack in Dhule. Phone: Shone Satheesh

Political reactions

......

Politically, the reaction to mob violence was either muted or in support of it. After the Bulandshahr killing, one BJP MLA argued that the policeman had actually shot himself and the rampaging mob had not role to play.

Prime Minister Modi had not said much on the violence in spite of the clear danger it represents. In 2017, he appealed for people to not take the law in their hands in case they suspect cow slaughter but allow the legal system to do its work (a large number of Indian states have made slaughtering cattle illegal). In 2019, Modi again condemned lynchings but also asked rhetorically if they began only in 2014.

So strong is the force of the mob that even the Opposition has been muted on the issue. The Congress has said little on how it intends to tackle lynchings and neither have any of the other parties in North and West India even as the general elections approach.

The only movement on the issue has been from WhatsApp, by far India’s most popular mobile phone messaging service. In July, 2018, the company limited forwarding of messaged to five chats at a time in a bid to curb rumours.

Read full article: scrollin

Friday, February 22, 2019

The Visionary

Azim Premji is not only one of India's biggest entrepreneurs, he is also the face of corporate philanthropy.

Rukmini Rao New Delhi

Azim Premji (Photograph by Hemant Mishra)

Nearly half a decade ago, the untimely death of his father forced Azim Hashim Premji, who was then at Stanford pursuing engineering, to abruptly leave his studies and return to India. Taking over his family's vegetable oil business at the age of 21 in 1966, over the course of next 20 years, Premji diversified Wipro's interests, from IT products to engineering services, and from medical equipment solutions to FMCG.

In an interview to a television channel, recalling his early days, Premji spoke of the scepticism that a shareholder had when he took over the company. "His comment really got my determination up to prove him wrong," Premji said. With no prior experience of managing a company, all Premji had was his ability to work hard.

"His biggest strength is perhaps tenacity; the ability to focus and then work single mindedly towards the goal," says Yasmeen Premji, his wife. The two had met in what was then Bombay and later married.

Yasmeen Premji, Azim Premji's wife

*******

Apart from being one of India's biggest entrepreneurs, Premji is undoubtedly the face of corporate philanthropy in the country. He established the Azim Premji Foundation in 2001 with a focus on education, especially girls. Till date, he has committed over $10 billion to various philanthropic causes through his Trust and family office. Joining the league of Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, Premji was the first Indian to give away over $2 billion to Giving Pledge in 2013. Under the foundation, Premji has also set up the Azim Premji University in Bengaluru in 2010.

Last year, while interacting with school and college students during Wipro Earthian awards ceremony, Premji was asked about his goal in life. He answered: "To be successful in what I do and to the best of what I can do." A motto that drives him even today at the age of 73.

Read full article: businesstoday

Rukmini Rao New Delhi

Azim Premji (Photograph by Hemant Mishra)

Nearly half a decade ago, the untimely death of his father forced Azim Hashim Premji, who was then at Stanford pursuing engineering, to abruptly leave his studies and return to India. Taking over his family's vegetable oil business at the age of 21 in 1966, over the course of next 20 years, Premji diversified Wipro's interests, from IT products to engineering services, and from medical equipment solutions to FMCG.

In an interview to a television channel, recalling his early days, Premji spoke of the scepticism that a shareholder had when he took over the company. "His comment really got my determination up to prove him wrong," Premji said. With no prior experience of managing a company, all Premji had was his ability to work hard.

"His biggest strength is perhaps tenacity; the ability to focus and then work single mindedly towards the goal," says Yasmeen Premji, his wife. The two had met in what was then Bombay and later married.

Yasmeen Premji, Azim Premji's wife

*******

Apart from being one of India's biggest entrepreneurs, Premji is undoubtedly the face of corporate philanthropy in the country. He established the Azim Premji Foundation in 2001 with a focus on education, especially girls. Till date, he has committed over $10 billion to various philanthropic causes through his Trust and family office. Joining the league of Warren Buffett and Bill Gates, Premji was the first Indian to give away over $2 billion to Giving Pledge in 2013. Under the foundation, Premji has also set up the Azim Premji University in Bengaluru in 2010.

Last year, while interacting with school and college students during Wipro Earthian awards ceremony, Premji was asked about his goal in life. He answered: "To be successful in what I do and to the best of what I can do." A motto that drives him even today at the age of 73.

Read full article: businesstoday

Friday, February 08, 2019

The Bengali artist who popularised the ‘wet sari effect’ and invented a new genre of figure painting

BOOK EXCERPT

Through his intimate works, Hemen Mazumdar changed the way women were depicted in Indian art.

Partha Mitter

Feb 06, 2019 · 11:30 am

'Monsoon', 25.5x36.7 cm, watercolour on paper. | Image courtesy: Kumar Collection.

Hemendranath Mazumdar (1898-1948) was born in a landowning family in Bengal. He enrolled at the art school in Calcutta against his father’s wishes. Having fallen out with the authorities, he then moved to the privately-owned Jubilee Academy. Disillusioned with both art schools, he decided to teach himself figure drawing by means of books obtained from England. The role of reproductions in art books in the formation of colonial artists cannot be gainsaid. In the 1920s, he, Atul Bose, and the great Jamini Roy – the last two completed the course at Calcutta government art school – became close friends, making ends meet with artistic odd jobs, such as painting scenes for the theatre, or producing portraits of the deceased for the family based on photographs, which was a popular ‘Victorian’ custom in Bengal.

The group decided to set up an academic artists’ circle to challenge the onslaught of the Bengal School against academic artists. The group brought out an influential illustrated journal, Indian Academy of Art, in 1920, to win the Bengali public, and organised exhibitions to showcase academic artists from all around India. In addition, they needed to counteract the Bengal School journal, Rupam’s dominance. To ensure wide readership, the modestly priced but elegantly produced Indian Academy of Art covered a wide variety of topics. In addition to articles on art theory that expatiated on naturalism, it supplied art news and gossip, travelogues, short stories and humorous pieces. However, the ultimate intention of the Indian Academy of Art was to publicise the works of Mazumdar, Bose and Jamini Roy (who remained with them for a while but was gradually moving away from academic naturalism.) Colour plates of their prize-winning pictures dominated the issues. Here among other paintings, Mazumdar’s first major painting, Palli Pran (Soul of the Village), on the ‘wet sari effect’ was published.

Read article and paintings: scroll.in

Through his intimate works, Hemen Mazumdar changed the way women were depicted in Indian art.

Partha Mitter

Feb 06, 2019 · 11:30 am

'Monsoon', 25.5x36.7 cm, watercolour on paper. | Image courtesy: Kumar Collection.

Hemendranath Mazumdar (1898-1948) was born in a landowning family in Bengal. He enrolled at the art school in Calcutta against his father’s wishes. Having fallen out with the authorities, he then moved to the privately-owned Jubilee Academy. Disillusioned with both art schools, he decided to teach himself figure drawing by means of books obtained from England. The role of reproductions in art books in the formation of colonial artists cannot be gainsaid. In the 1920s, he, Atul Bose, and the great Jamini Roy – the last two completed the course at Calcutta government art school – became close friends, making ends meet with artistic odd jobs, such as painting scenes for the theatre, or producing portraits of the deceased for the family based on photographs, which was a popular ‘Victorian’ custom in Bengal.

The group decided to set up an academic artists’ circle to challenge the onslaught of the Bengal School against academic artists. The group brought out an influential illustrated journal, Indian Academy of Art, in 1920, to win the Bengali public, and organised exhibitions to showcase academic artists from all around India. In addition, they needed to counteract the Bengal School journal, Rupam’s dominance. To ensure wide readership, the modestly priced but elegantly produced Indian Academy of Art covered a wide variety of topics. In addition to articles on art theory that expatiated on naturalism, it supplied art news and gossip, travelogues, short stories and humorous pieces. However, the ultimate intention of the Indian Academy of Art was to publicise the works of Mazumdar, Bose and Jamini Roy (who remained with them for a while but was gradually moving away from academic naturalism.) Colour plates of their prize-winning pictures dominated the issues. Here among other paintings, Mazumdar’s first major painting, Palli Pran (Soul of the Village), on the ‘wet sari effect’ was published.

Read article and paintings: scroll.in

Friday, February 01, 2019

129 Indians out of 130 ‘students’ arrested in US ‘pay-and-stay’ immigration scam

HT Correspondent

Hindustan Times, Washington

An illegal immigrant in the United States illegally is checked before boarding a deportation flight by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). ICE authorities have arrested 130 people, 129 of them Indian, enrolled as students in a fake university in Detroit as an immigration fraud and will deport them (Representative Photo)(AP)

The arrested Indians have been placed in “removal proceedings” — marked for deportation, in other words — and will remain in the custody of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) until the conclusion of their case by immigration courts.

********

Most of the affected are from Telengana and Andhra Pradesh and are also receiving help from community associations. One of them, the American Telugu Association has launched a webpage to help the students and organized a webinar with immigration lawyers to guide them “to be watchful with fake agents who promise illegal ways to stay in USA with admissions in unaccredited colleges”.

Read full article: hindustantimes

Hindustan Times, Washington

An illegal immigrant in the United States illegally is checked before boarding a deportation flight by U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). ICE authorities have arrested 130 people, 129 of them Indian, enrolled as students in a fake university in Detroit as an immigration fraud and will deport them (Representative Photo)(AP)

The arrested Indians have been placed in “removal proceedings” — marked for deportation, in other words — and will remain in the custody of US Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) until the conclusion of their case by immigration courts.

********

Most of the affected are from Telengana and Andhra Pradesh and are also receiving help from community associations. One of them, the American Telugu Association has launched a webpage to help the students and organized a webinar with immigration lawyers to guide them “to be watchful with fake agents who promise illegal ways to stay in USA with admissions in unaccredited colleges”.

Read full article: hindustantimes

Wednesday, January 09, 2019

Wednesday, December 26, 2018

Arrival of the Black Ships: A turning point that saw Japan emerge from centuries of self-isolation

History revisited

The existential threat posed by the American warships in 1853 led to deep divisions with the ruling elite and the population.

A Japanese print showing three men, believed to be Commander Anan, age 54; Perry, age 49; and Captain Henry Adams, age 59, who opened up Japan to the west | Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons [Licnesed under CC BY Public Domain Mark 1.0]

Hamish Todd

December 26th 2018

"During the Meiji Period (1868-1912), Japan was transformed from a feudal society where power lay in the hands of the Tokugawa Shoguns and hundreds of local lords or Daimyo controlling a patchwork of fiefdoms, to a centralised, constitutional state under the nominal leadership of Emperor Mutsuhito (1852-1912). This transition was marked by the inauguration of the new reign name of Meiji or “Enlightened Rule” on October 23, 1868.

To commemorate this major anniversary, the British Library has digitised a manuscript handscroll Or.16453 depicting the arrival in Japanese waters in July 1853 of the American Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) and his squadron of four warships. Perry’s arrival triggered a long chain of events that led ultimately to the revolution of 1868."

Read article: Scrollin

The existential threat posed by the American warships in 1853 led to deep divisions with the ruling elite and the population.

A Japanese print showing three men, believed to be Commander Anan, age 54; Perry, age 49; and Captain Henry Adams, age 59, who opened up Japan to the west | Library of Congress/Wikimedia Commons [Licnesed under CC BY Public Domain Mark 1.0]

Hamish Todd

December 26th 2018

"During the Meiji Period (1868-1912), Japan was transformed from a feudal society where power lay in the hands of the Tokugawa Shoguns and hundreds of local lords or Daimyo controlling a patchwork of fiefdoms, to a centralised, constitutional state under the nominal leadership of Emperor Mutsuhito (1852-1912). This transition was marked by the inauguration of the new reign name of Meiji or “Enlightened Rule” on October 23, 1868.

To commemorate this major anniversary, the British Library has digitised a manuscript handscroll Or.16453 depicting the arrival in Japanese waters in July 1853 of the American Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry (1794-1858) and his squadron of four warships. Perry’s arrival triggered a long chain of events that led ultimately to the revolution of 1868."

Read article: Scrollin

Subscribe to:

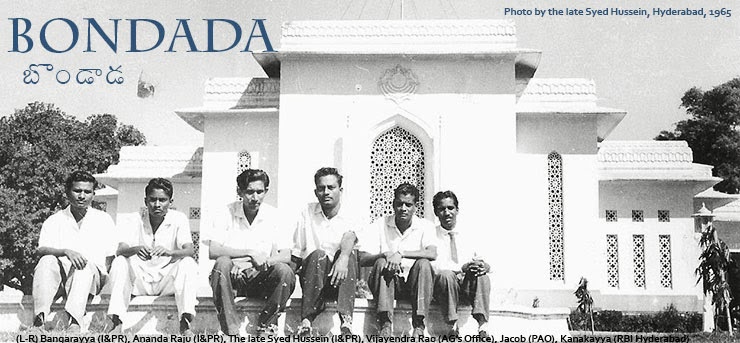

Posts (Atom)