Illustration by Zack Stanton. Photo via Adam Singer, CC BY 2.0

Colonial India's World War One efforts transformed the Middle East — and India, too.

NEARLY 30 KILOMETERS SOUTHWEST OF BASRA, just off the open road to Nasiriyya, stands a sun-bleached stone monument to a forgotten era. In contrast to the grandeur of some of Iraq’s more modern monuments, the Basra War Memorial blends modestly and unobtrusively into the surrounding sandy desert. Its windswept and dilapidated stone edifice commemorates the 40,500 members of the British Empire’s operations in Mesopotamia whose final resting places are unknown. Among those names chiseled into immortality in the lengthy stone walkway framing a central pillar are the sons of India. An engraved sentence “as sad as any I’ve read in war” caught the eye of BBC reporter Fergal Keane while he accompanied coalition troops during the 2003 Iraq war: “It says simply: For Subhadar Mahanga and 1,770 other Indian soldiers.”

Such unassuming memorials as in that empty stretch of desert near Basra pay tribute to the extraordinary sacrifice of Indian soldiers, among others, who deployed to fight in the Great War. Yet despite these soldiers’ journeys across the seas and into the heartland of the Ottoman Empire, the Indian contribution to World War I in the Middle East is considerably less acknowledged outside the British Isles and the Indian subcontinent.

In truth, the links between the Middle East and South Asia go back centuries; the Great War served to bring the two populations even closer and in larger numbers than ever before. It was Indians, Egyptians, Australians, and other colonial subjects who manned the trenches and peopled the platoons that fought and won the war in the Middle East for the British. The presence of such large numbers of foreigners in the heart of the Middle East represented an opening that built on centuries-old contacts between South Asia and the Middle East.

As 1914 dawned, major combat operations seemed a distant prospect to the soldiers of the Indian army. At the start of monsoon season that summer, the Indian army comprised a mere 155,000 men organized into nine divisions and eight cavalry brigades. To the Indian soldier of early 1914, it would have been unimaginable that by the time the Armistice was signed four years later, India would provide one-tenth of the manpower of the British war effort — more than 1.27 million men, including 827,000 combatants. Altogether, nearly 60,000 Indians died fighting for the crown on the battlefields of Mesopotamia and France.

EARLY IN THE CONFLICT, BRITAIN insisted on conscripting only particular types of Indians. Since the 1850s, British military recruitment efforts bypassed the educated masses of urban India and instead focused on the illiterate teenage peasants from north and northwest — a region that was, by 1914, home to 80 percent of India’s 57 million Muslims — whom the Brits saw as infused with a warrior spirit.

At the outset of the Great War, Punjab alone accounted for 60 percent of India’s military conscripts. Their ranks were joined by Sikhs, Rajputs, Gurkhas, Jats, Dogras, Pathans, Hindustani Muslims, Ahirs, and almost 70 other population groups. Together, they crossed the Indian Ocean into foreign lands to do battle on behalf of the Crown.

In organizing their Indian forces, the British reinforced martial class demarcations by assigning recruits to ethnically, spiritually, or linguistically homogeneous companies and even regiments. Emphasizing group distinctions mitigated the potential for uprising, as the distinctive “religious practices, dietary restrictions and religious ceremonies” of homogeneously constructed regiments fostered separate and cohesive identities. The hierarchy of Indian society, transplanted to the battlefield, shaped the interactions of, and colored the relationships within, Indian units. As losses undermined homogeneity and replacement officers dwindled in quality and numbers, Indian units suffered along with their British counterparts.

Yet unlike their British counterparts, few Indians rode the wave of emotional patriotism that swept the home isles. Historian David Omissi’s careful combing of Indian soldiers’ war letters shows that “people never mentioned in the letters read like a political Who’s Who of World War I: Woodrow Wilson, Lloyd George, Herbert Asquith, Lenin, Trotsky, and Gandhi.” More than anything, it seems that the focus, instead, on family, clan, and caste helped inspire the Indian soldiers as warfare intensified from frontier patrols to frontal charges.

The Ottomans were well aware of the Indian Muslim presence in the British lines, and they moved promptly to exploit their status as coreligionists. Because almost one-third of these new infantrymen with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force were Muslim, Ottoman frontline patrols were accompanied by the regimental imam, who would sing prayers at the British troops, hoping to lure defectors. In response, British staff officers intensified their vigilance when Indian soldiers were on leave in contact with Ottomans. Intelligence officers at Suez, Ismailia, and al-Qantara kept watch for Ottoman propaganda, while military police toured frontline divisions, showing soldiers photographs of the appalling conditions of Indian prisoners of war. When possible, leave parties were organized to Jerusalem to visit religious sites; after the end of hostilities, small groups were able to participate in the pilgrimage to Mecca.

In retrospect, the Ottoman effort was mostly ineffective at sparking Indian military defections. When religion proved ineffective, the Ottomans attempted other propaganda strategies. One Indian battalion in Mesopotamia was greeted by a shower of Hindi pamphlets warning them that “England was starving and would soon be unable to feed and clothe them.” The Indian officers wrote a reply and requested it be dropped on the Ottomans. It included the lines, “We have never been fed and clothed so well, but prisoners taken from you are in rags. … We will never cease to fight for the King Emperor Jarj Panjam [George V] until the evil Kaiser is utterly trodden into the mud.”

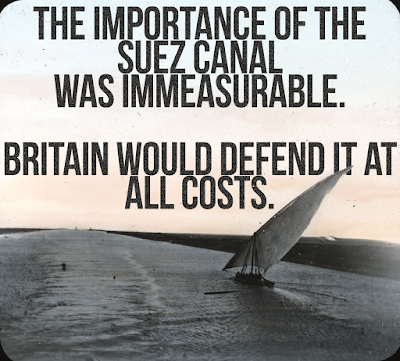

A ship

travels the Suez Canal early in the 20th century. Lantern slide image via

Brooklyn Museum, GoodyearArchival Collection. Colored by Joseph Hawkes.

Soldiers: India and Pakistan in the Great War

By Leila Tarazi FawazColonial India's World War One efforts transformed the Middle East — and India, too.

NEARLY 30 KILOMETERS SOUTHWEST OF BASRA, just off the open road to Nasiriyya, stands a sun-bleached stone monument to a forgotten era. In contrast to the grandeur of some of Iraq’s more modern monuments, the Basra War Memorial blends modestly and unobtrusively into the surrounding sandy desert. Its windswept and dilapidated stone edifice commemorates the 40,500 members of the British Empire’s operations in Mesopotamia whose final resting places are unknown. Among those names chiseled into immortality in the lengthy stone walkway framing a central pillar are the sons of India. An engraved sentence “as sad as any I’ve read in war” caught the eye of BBC reporter Fergal Keane while he accompanied coalition troops during the 2003 Iraq war: “It says simply: For Subhadar Mahanga and 1,770 other Indian soldiers.”

Such unassuming memorials as in that empty stretch of desert near Basra pay tribute to the extraordinary sacrifice of Indian soldiers, among others, who deployed to fight in the Great War. Yet despite these soldiers’ journeys across the seas and into the heartland of the Ottoman Empire, the Indian contribution to World War I in the Middle East is considerably less acknowledged outside the British Isles and the Indian subcontinent.

In truth, the links between the Middle East and South Asia go back centuries; the Great War served to bring the two populations even closer and in larger numbers than ever before. It was Indians, Egyptians, Australians, and other colonial subjects who manned the trenches and peopled the platoons that fought and won the war in the Middle East for the British. The presence of such large numbers of foreigners in the heart of the Middle East represented an opening that built on centuries-old contacts between South Asia and the Middle East.

As 1914 dawned, major combat operations seemed a distant prospect to the soldiers of the Indian army. At the start of monsoon season that summer, the Indian army comprised a mere 155,000 men organized into nine divisions and eight cavalry brigades. To the Indian soldier of early 1914, it would have been unimaginable that by the time the Armistice was signed four years later, India would provide one-tenth of the manpower of the British war effort — more than 1.27 million men, including 827,000 combatants. Altogether, nearly 60,000 Indians died fighting for the crown on the battlefields of Mesopotamia and France.

EARLY IN THE CONFLICT, BRITAIN insisted on conscripting only particular types of Indians. Since the 1850s, British military recruitment efforts bypassed the educated masses of urban India and instead focused on the illiterate teenage peasants from north and northwest — a region that was, by 1914, home to 80 percent of India’s 57 million Muslims — whom the Brits saw as infused with a warrior spirit.

At the outset of the Great War, Punjab alone accounted for 60 percent of India’s military conscripts. Their ranks were joined by Sikhs, Rajputs, Gurkhas, Jats, Dogras, Pathans, Hindustani Muslims, Ahirs, and almost 70 other population groups. Together, they crossed the Indian Ocean into foreign lands to do battle on behalf of the Crown.

In organizing their Indian forces, the British reinforced martial class demarcations by assigning recruits to ethnically, spiritually, or linguistically homogeneous companies and even regiments. Emphasizing group distinctions mitigated the potential for uprising, as the distinctive “religious practices, dietary restrictions and religious ceremonies” of homogeneously constructed regiments fostered separate and cohesive identities. The hierarchy of Indian society, transplanted to the battlefield, shaped the interactions of, and colored the relationships within, Indian units. As losses undermined homogeneity and replacement officers dwindled in quality and numbers, Indian units suffered along with their British counterparts.

Yet unlike their British counterparts, few Indians rode the wave of emotional patriotism that swept the home isles. Historian David Omissi’s careful combing of Indian soldiers’ war letters shows that “people never mentioned in the letters read like a political Who’s Who of World War I: Woodrow Wilson, Lloyd George, Herbert Asquith, Lenin, Trotsky, and Gandhi.” More than anything, it seems that the focus, instead, on family, clan, and caste helped inspire the Indian soldiers as warfare intensified from frontier patrols to frontal charges.

The Ottomans were well aware of the Indian Muslim presence in the British lines, and they moved promptly to exploit their status as coreligionists. Because almost one-third of these new infantrymen with the Egyptian Expeditionary Force were Muslim, Ottoman frontline patrols were accompanied by the regimental imam, who would sing prayers at the British troops, hoping to lure defectors. In response, British staff officers intensified their vigilance when Indian soldiers were on leave in contact with Ottomans. Intelligence officers at Suez, Ismailia, and al-Qantara kept watch for Ottoman propaganda, while military police toured frontline divisions, showing soldiers photographs of the appalling conditions of Indian prisoners of war. When possible, leave parties were organized to Jerusalem to visit religious sites; after the end of hostilities, small groups were able to participate in the pilgrimage to Mecca.

That many Indians were

Muslim was a source of angst for the British military— and a wellspring of

possibility for the Ottoman Empire.

In retrospect, the Ottoman effort was mostly ineffective at sparking Indian military defections. When religion proved ineffective, the Ottomans attempted other propaganda strategies. One Indian battalion in Mesopotamia was greeted by a shower of Hindi pamphlets warning them that “England was starving and would soon be unable to feed and clothe them.” The Indian officers wrote a reply and requested it be dropped on the Ottomans. It included the lines, “We have never been fed and clothed so well, but prisoners taken from you are in rags. … We will never cease to fight for the King Emperor Jarj Panjam [George V] until the evil Kaiser is utterly trodden into the mud.”

The Ottoman effort failed in

part because so many Indian Muslims separated political duty from religious

fealty, thereby easing their anxieties over the war. But that loyalty sometimes

strained to overcome cultural obstacles. Sikhs, for example, refused to wear

steel shrapnel helmets, citing religious prohibitions against the wearing of

such hats. Meanwhile, the war diary of a Punjabi regiment describes the

challenges the British faced during one cholera inoculation campaign in

Mesopotamia in the spring of 1916: “The Khattacks except the Indian officers

and NCOs refused to be done as they still believed the stories they had heard

in Egypt about all inoculation rendering men impotent. Even when told in turn

that this inoculation was not voluntary but by order they still refused, and

had to be marched back to camp under arrest. Subedar Major Mir Akbar found out

who was at the bottom of this refusal and persuaded them to agree to be

inoculated the following day.”

Indian

British artillery in Palestine; conflicting dates of 1917 and 1920. Photo via

Library of Congress.

DESPITE THE BEST EFFORTS OF

THE BRITISH,

public opinion in colonial India included a noticeable sympathy for the

Ottomans. As with troops in the field, on the Indian subcontinent, an attempt

was made to limn out a distinction between the political and religious aspects

of the war — an attempt with limited success.

The removal of the partition

of Bengal in 1911 had encouraged Indian Muslims predisposed to extraneous

cultural influences and sensitive to their Muslim status to reflect on their

loyalties. Such potentially pro-Ottoman predispositions were given voice in

newspapers such as Comrade, Hamdard, Al-Hilal, and Zamindar,

which expressed regret at the Ottoman entry into the war but emphasized

pan-Islamic solidarity, the sacredness of the Islamic holy sites, the British

annexation of Egypt, and Ottoman victories in places such as Gallipoli.

At the beginning of the war,

Sultan Mehmed V issued a fatwa for jihad in order to address the question of

loyalty: “The Moslem subjects of Russia, of France, of England and of all the

countries that side with them in their land and sea attacks dealt against the

Caliphate for the purpose of annihilating Islam, must these subjects, too, take

part in the Holy War against the respective governments from which they depend?

Yes.”

The British fear of uprising was

real during the war, but after 1915 the threat never rose above mere potential.

Ultimately, proof of Indian sympathy for the Ottoman caliphate emerged after

the war in the form of the Khilafat movement of 1919 to 1924, organized by

Muslims in India in support of the Ottoman Empire. None other than Mahatma

Gandhi lent strong support to the cause of the Khilafat during the mass

noncooperation movement against the British in the aftermath of the Great War.

For Indians both at home and

in the military, tales told by the returning wounded constituted a central

source of news and information. Alarming reports of drought and disease began

to reach the front in 1915, compounding such anxieties among soldiers. The

impressions created were of a brutal, grim conflict — sowing doubts among

prospective Indian soldiers who weighed the promised rewards for enlistment

against the dangers of combat. Punjabi folks songs from the era maintain a

telling emotional distance from all the war’s partisans, and a conviction that

for the poor, war, above all, meant suffering.

Ultimately, Ottoman

efforts to exploit this shared religious identity failed, in part because so

many Indian Muslims separated political duty from religious fealty.

Although Indian soldiers knew

their missives faced the probing eyes of British censors — and therefore likely

shaped their letters to pass muster — some felt a genuine connection to the

war. One soldier wrote that this was “the time to show one’s loyalty to the

Sirkar, to earn a name for oneself. To die on the battlefield is glory. For a

thousand years, one’s name will be remembered.” Bonds forged in the crucible of

trench combat reinforced morale. Echoing a refrain heard across military

history, one soldier confided, “I cannot describe to you how great fascination

there is in fighting at the front. One experiences a feeling of exhilaration.”

These concomitant feelings of

loyalty and exhilaration were doubly tested at the outset of Sharif Husayn’s

Arab Revolt in June 1916. It was a jolting event for Indian Muslims, whose

incredulity hardened into criticism at the revolt for risking the sanctity of

Islam’s holy sites. Throughout India, anti-Arab feeling was apparent; the

All-India Muslim League in Lucknow embodied the reaction of political actors across

Muslim India: “The Arab rebels headed by the Sharif of Mecca, whose outrageous

conduct may place in jeopardy the safety and sanctity of the holy places of

Islam in the Hejaz and Mesopotamia.”

Nonetheless, in the letters

that Omissi curates, ideological discussions or broader political dynamics

generally rank behind concerns of the familial strains caused by war. One

Punjabi soldier argued that while “those who do not put their hearts into the

work of fighting the King’s enemies are clearly worthy of the greatest blame,”

it is incumbent on the king to ameliorate the burdens of extended deployment.

He continued, “[The Caliph] Hazrat Umar … had a law passed that in future every

married soldier should be allowed to return to his home on leave once every six

months. I have been astonished to think that when we have such a King, renowned

throughout the world for his kindness and justice, he has never considered this

problem.”

Indian soldiers faced a

mixture of socioeconomic hardship and ideological pressure. Some units mutinied

rather than face their brethren on the battlefield, while some Pathans even

fired on their own sentries before deserting their ranks. According to official

figures, after four years of war almost half of the Punjabi deserters remained

at large. Some soldiers worried about the desertions and what they said about

the honorability of the overall unit. Others worried over the condition of

their Indian comrades who were imprisoned after mutinying. As the war ground

on, an increasing number sought to escape the front through self-inflicted

wounds, often to their left hands and feet, while night blindness in one unit

was discovered to be mostly self-induced.

FOR GREAT BRITAIN, EGYPT'S

STRATEGIC VALUE was

immeasurable: an equidistant geopolitical hub between the Middle East and

Europe for deployments ranging from Basra to Marseilles. Since the British

takeover of Egypt in 1882, maintaining control over the Suez Canal became the sine

qua non of London’s regional strategy. Thirty-four feet deep, 100 miles

long, and 190 feet wide at minimum, the Suez Canal constituted a formidable

waterway, more than one-third of which was naturally protected by lakes and

floodplains. The rest, however, would need to be protected by troops. It would

be defended at all costs.

By January 1915 the British

had increased the Suez defense to 70,000 soldiers drawn from across the empire:

Indians, Australians, New Zealanders, all united to defend the canal. Although

the government controlled any reporting on troop movements, the disembarkation

of thousands of Indians at railway stations inevitably sparked curiosity. “The

streets of Egypt were packed with English and Indian soldiers staying at

Heliopolis and Zeytun,” al-Ahram reported. “The crowds gathered to watch

them and some thought that the Indians looked exactly like the Japanese.” In

Egypt, separate military encampments did limit somewhat the interaction between

Indians and Egyptians, and British apprehension at the prospect of thousands of

Indian men stationed in Egypt caused them to declare Port Said — a noted

prostitution center — as entirely “out of bounds.” Some, however, readily

resigned themselves to their new milieu, even taking to their new setting

enthusiastically. In four years of war, India sent 95,000 combatants and 135,000

noncombatants to the Egyptian and Palestine front.

Scouts

for an Indian cavalry regiment pause to consult a map near Vraignes,

France; April 1917. Photo via Imperial War Museum.

IN THE PREDAWN HOURS OF EARLY

FEBRUARY 1915,

Indian sentries spied the silhouetted mass of an Ottoman attacking force

silently pushing off the east bank of the Suez and making its way toward their

defensive works. In the ensuing battle, Punjabis trained heavy fire on pontoons

and other amphibious assault craft, sinking them in rapid succession, with

Rajputs, Egyptians, and Sikhs participating in the operation.

As one of the first

Egyptian-Indian actions of the war against the Ottomans, the first Suez

offensive set the tone for the ensuing battle over Palestine. Several Indian

divisions saw action on disparate fronts from the lush countryside of France to

the barren desert of Mesopotamia. Then, following the surrender of Baghdad,

these troops joined newly arrived Indian cavalry — redeployed from Europe — to

help form the Egyptian Expeditionary Corps.

Although they would win him

brilliant victories, culminating in the Battle of Megiddo in northern Palestine

in September 1918, Field Marshal Edmund Allenby, leader of the Egyptian

Expeditionary Force, invoked some of the same stereotypes as his contemporaries

in discussing his colonial men. In the aftermath of one Pathan outpost

deserting to the Ottomans, Allenby was piqued. “If I could be reinforced by 3

or 4 good divisions … I could, I think, really get a move on my Turks.” So it must

have been disheartening to Allenby when in late 1917 London accelerated the

“Indianization” of his force.

Increasing the number of

Indians in the Egyptian Expeditionary Corps was Britain’s effort to build up

Allenby’s troops “without having to make recourse to fresh drafts from Britain,

which was facing accumulating manpower problems.” British planners also hoped

to draw on the organizational skills and combat experiences of Indian units

acclimated to three years of war in the Middle East. The perceived downside to

such a move was the risk of stationing in Palestine large numbers of Indian

Muslims in direct opposition and proximity to their Ottoman coreligionists. By

late 1917, the gears of the Indian recruiting system were rotating at full

speed, enabling such a policy shift.

The increasing

“Indianization” of Britain’s army was born of necessity and occurred

amidst British jitters over stationing Indian Muslims in proximity to

their Ottoman coreligionists.

On December 11, 1917, Allenby

dismounted and walked into Jerusalem, prompting Prime Minister Lloyd George to

advocate a major offensive to break out into Greater Syria, thereby refocusing

“a Eurocentric effort he regarded as counterproductive.” In response, Allenby

submitted his resourcing requirements for further action. Allenby’s plans,

however, were soon interrupted by a massive, last-ditch German offensive

launched in March 1918 in Flanders and France, an attack that ripped large

holes in two British armies. Allenby’s hopes for British reinforcements died

along with entire divisions in the fields of Flanders and France. As the War

Office rapidly recalled troops to Europe to stem the rising German tide, the

pace of “Indianization” in Palestine quickened. While Allenby’s deceptions

eventually outmaneuvered the Germans and Ottomans, the war itself was fought

and won largely by an Indian and Egyptian force.

Integral to that victory was

“the last great cavalry campaign in history.” Although Indian infantry

prepared, assaulted, and broke through the Ottoman lines during Allenby’s fall

offensive, it was the Desert Mounted Corps that pushed through the Ottoman gaps

and prevented an orderly Ottoman retreat. This sweeping cavalry ride

accomplished what European troops had been unable to do in the stalemate of

Europe. New York Times correspondent W. T. Massey reported on “great feats by

the cavalry” and described Indian charges: “brilliantly … perfectly

timed … masterly success … a feat almost without parallel in this war.”

As in past conflicts, the

cavalry also served as raiders and intelligence gatherers. Charles Trench, an

Indian army officer in the 1930s who became known for his popular historical

works, relates one such raid during the “dash up the coast:”

Just short of Damascus a

squadron of the Poona Horse charged in error a body of Arabs who proved too

elusive for them. They did, however, bag a large motor-car containing a

European splendidly Arab-garbed. Suspecting a German spy, Risaldar Major Hamir

Singh demanded his surrender, and there ensued a heated altercation, neither

understanding one word the other said. It transpired that this individual’s

name was Lawrence, and that he had something to do with the Sharif of Mecca’s

forces.

As Trench suggests, this

incident may in part account for T. E. Lawrence’s general bias toward the

Indian army. The incident notwithstanding, Allenby’s attack — up the coastal

plain, through the central Palestinian highlands, and across the Jordan River

valley — inspired pride among Indian troops. Testifying to their momentum, in

all of 1918 the Egyptian Expeditionary Force suffered only a few dozen

desertions.

That is not to say, however,

that Allenby’s thrust through Palestine was simple. Although it is often

portrayed as swift and active in comparison to the static European front,

conditions in Palestine were far from ideal and cost Allenby 9,980 Indian and

native troops. While British captains often fixed bayonets and ordered charges,

it was mostly Indian units who executed those orders. Their suffering is

exemplified in the Indian experience at Kut, while their determination was

rewarded with the eventual capture of Baghdad.

Indeed, it was in Mesopotamia

where the pain of defeat and the exhilaration of victory merged into one.

Indian

troops man a three-pound, wagon-mounted Hotchkiss gun on the railway between

Basra and Nasiriya. Photo via Imperial War Museum

IT BEGAN IN NOVEMBER 1914, when the Indian Sixth

Division was dispatched to capture Basra and secure the Anglo-Persian oil

installations. Facing them in Mesopotamia were 17,000 infantrymen, 380 cavalry,

44 field guns, and three machine guns. By the time of the Armistice, over 600,000

Indian men had, in one form or another, experienced the great convulsion of

Mesopotamian warfare. In the beginning, a large-scale war along the Tigris

seemed unlikely. However, after a series of initial victories, British

decision-makers were tempted by the ease of their early advances and cast

strategic prudence aside.

Lord Hardinge, the British

viceroy, argued in November 1915 that “our success hitherto in Mesopotamia has

been the main factor which has kept Persia, Afghanistan, and India itself

quiet.” Ultimately, however, the blame for one of the greatest catastrophes in

British military history — the defeat at Kut — rests on the commanders on the

spot, in particular General John Nixon. Nixon’s preference for an ethos of

inspirational leadership came at the expense of logistical preparation. The

Tigris expedition faced one logistical hurdle after another; unfortunately,

Nixon’s confidence in the fighting spirit of his men came at the expense of

such indispensable work as the development of the port of Basra. Martial valor

proved no substitute for careful preparation.

From the beginning, life

inside besieged Kut was emotionally and physically torturous. As the historian

Nikolas Gardner has detailed, the Ottomans bombarded Kut with “leaflets printed

in various Indian languages calling on sepoys to murder their British officers

and join the Turks.” As elsewhere, this Ottoman initiative had little effect,

but it reminded Townshend of the dilemma Indian soldiers faced fighting in a

foreign land against coreligionists while subsisting on inadequate provisions

and receiving insufficient medical care. As the siege dragged on, conditions

only worsened.

On January 20, 1916, as the

prospect of immediate relief was dwindling and vegetables and other food grew

scarce inside Kut, Townshend ordered his men to halve their rations. The

garrison’s tinned meat supplies gave way to an even less appetizing reality:

the consumption of pack animals.

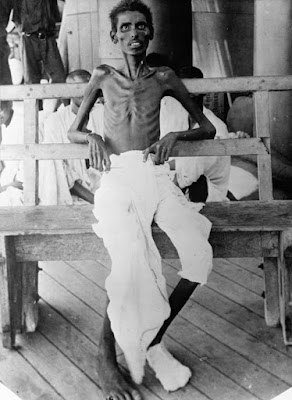

An

emaciated Indian soldier who survived the siege at Kut. Photo via Imperial War

Museum.

Although famished, many

Indians refused to incorporate horse and mule into their daily diet, as they

considered themselves prohibited by religious rules from doing so, and fretted

that their comrades would share news of this trespass upon returning home.

Townshend sought to overcome his soldiers’ hesitations by soliciting statements

from Indian religious leaders, posted throughout Kut, “sanctioning the

consumption of horseflesh.”

Moreover, the soldiers’

reliance on diminishing and inadequate rations of flour and unprocessed grain

led to outbreaks of pneumonia, jaundice, and dysentery at alarmingly high

levels. On March 7, 1916, the daily ration was set at 10 ounces of barley flour

and four of parched barley grain; by the end of the month, rations were further

reduced to six and four ounces, respectively. In mid-April, after rations were

reduced to four ounces of flour, roughly 10,000 Sikhs, Hindus, and Muslims

relented and began consuming horsemeat. For some, it was already too late; by

one author’s documentation, in consuming less than half of the calories

necessary to maintain their strength, British soldiers lost an average of 12.5

pounds, while Indians lost approximately 17 pounds during the siege. Reads one

soldier’s memoir: “We are a sick army, a skeleton army rocking with cholera and

disease.” A small percentage of the force despaired; desertions rose, and

others committed suicide.

Surrender followed. Conditions

did not change quickly after the fall of Kut. One major summarized the state of

conditions while entrenched with Punjabis in simple, unexaggerated staccato:

“Heat is appalling and only just beginning. Flies bite hard and are in

thousands. Cholera has started. … We lie and gasp all day. … Meals are

practically an impossibility on account of the flies.” He later describes a

march in which “men fell like flies” as more than “1,000 collapsed from heat

and lack of water. … Men simply crumpled up.”

These conditions were endured

by a particularly large number of Indian soldiers, since more than twice as

many fought in Mesopotamia as in France (or Palestine). The influence of these

theaters could not have been equal; Mesopotamia, more than Palestine or France,

shaped the Indian soldier.

Thirty percent of the Indian

force would not survive their Ottoman internment.

IN THE GREAT WAR, SOUTH ASIANS

WERE CRITICAL to

Triple Entente victories around the Gulf, in Palestine, and throughout Greater

Syria. This fact alone justifies paying increased attention to the Indians who

fought in the Middle East, especially when compared to the enormous scholarship

devoted to their European counterparts. Set aside their military contributions,

however, and an additional rationale for studying these South Asians emerges.

It was Indians,

Egyptians, Australians, and other colonial subjects who manned the trenches and

peopled the platoons that fought and won the war in the Middle East for

the British.

By traveling across the Indian

Ocean and into the Middle East, these men experienced new worlds and new

people. In Palestine, they fought with the Arab Revolt; in Mesopotamia, they

suffered among rivertine tribes; on Gallipoli, they charged Ottoman Turks; and

in Cairo, they experienced cosmopolitan urbanites.

A diverse array of Indians

encountered an equally diverse group of Middle Easterners for four intensive

years, deepening and broadening a long-standing connection between the two

regions. As the Middle East transitioned into its postwar era, its interactions

and experiences with South Asia became an important part of its historical

memory.

* * *

Leila Tarazi Fawaz is Issam M. Fares Professor of Lebanese and Eastern

Mediterranean Studies at Tufts University. This piece is adapted from her

book, A Land of Aching Hearts:

The Middle East in the Great War, available from Harvard University Press

Source: wilsonquarterly