2 July 2015

IWM

Approximately

1.3 million Indian soldiers served in World War One, and over 74,000 of them

lost their lives. But history has mostly forgotten these sacrifices, which were

rewarded with broken promises of Indian independence from the British

government, writes Shashi Tharoor.

Exactly

100 years after the "guns of August" boomed across the European

continent, the world has been extensively commemorating that seminal event. The

Great War, as it was called then, was described at the time as "the war to

end all wars". Ironically, the eruption of an even more destructive

conflict 20 years after the end of this one meant that it is now known as the

First World War. Those who fought and died in the First World War would have

had little idea that there would so soon be a Second.

But while

the war took the flower of Europe's youth to its premature grave, snuffing out

the lives of a generation of talented poets, artists, cricketers and others

whose genius bled into the trenches, it also involved soldiers from faraway

lands that had little to do with Europe's bitter traditional hatreds.

The role

and sacrifices of Australians, New Zealanders, Canadians and South Africans

have been celebrated for some time in books and novels, and even rendered

immortal on celluloid in award-winning films like Gallipoli. Of the 1.3 million

Indian troops who served in the conflict, however, you hear very little.

As many

as 74,187 Indian soldiers died during the war and a comparable number were

wounded. Their stories, and their heroism, have long been omitted from popular

histories of the war, or relegated to the footnotes.

India

contributed a number of divisions and brigades to the European, Mediterranean,

Mesopotamian, North African and East African theatres of war. In Europe, Indian

soldiers were among the first victims who suffered the horrors of the trenches.

They were killed in droves before the war was into its second year and bore the

brunt of many a German offensive.

It was

Indian jawans (junior soldiers) who stopped the German advance at Ypres

in the autumn of 1914, soon after the war broke out, while the British were

still recruiting and training their own forces. Hundreds were killed in a

gallant but futile engagement at Neuve Chappelle. More than 1,000 of them died

at Gallipoli, thanks to Churchill's folly. Nearly 700,000 Indian sepoys

(infantry privates) fought in Mesopotamia against the Ottoman Empire, Germany's

ally, many of them Indian Muslims taking up arms against their co-religionists

in defence of the British Empire.

The most

painful experiences were those of soldiers fighting in the trenches of Europe.

Letters sent by Indian soldiers in France and Belgium to their family members

in their villages back home speak an evocative language of cultural dislocation

and tragedy. "The shells are pouring like rain in the monsoon,"

declared one. "The corpses cover the country, like sheaves of harvested

corn," wrote another.

IWM Image

caption King George V inspecting Indian troops at Le Cateau in 1918

These men

were undoubtedly heroes - pitchforked into battle in unfamiliar lands, in harsh

and cold climatic conditions they were neither used to nor prepared for,

fighting an enemy of whom they had no knowledge, risking their lives every day

for little more than pride. Yet they were destined to remain largely unknown

once the war was over: neglected by the British, for whom they fought, and

ignored by their own country, from which they came.

Part of

the reason is that they were not fighting for their own country. None of the

soldiers was a conscript - soldiering was their profession. They served the

very British Empire that was oppressing their own people back home.

The

British raised men and money from India, as well as large supplies of food,

cash and ammunition, collected both by British taxation of Indians and from the

nominally autonomous princely states. In return, the British had insincerely

promised to deliver progressive self-rule to India at the end of the war.

Perhaps, had they kept that pledge, the sacrifices of India's First World War

soldiers might have been seen in their homeland as a contribution to India's

freedom.

But the

British broke their word. Mahatma Gandhi, who returned to his homeland for good

from South Africa in January 1915, supported the war, as he had supported the

British in the Boer War. The great Nobel Prize-winning poet, Rabindranath

Tagore, was somewhat more sardonic about nationalism. "We, the famished,

ragged ragamuffins of the East are to win freedom for all humanity!" he

wrote during the war. "We have no word for 'nation' in our language."

India was

wracked by high taxation to support the war and the high inflation accompanying

it, while the disruption of trade caused by the conflict led to widespread

economic losses - all this while the country was also reeling from a raging

influenza epidemic that took many lives. But nationalists widely understood

from British statements that at the end of the war India would receive the

Dominion Status hitherto reserved for the "White Commonwealth".

Getty

Images Troops on the beach on Cape Helles as stores are being

unloaded during the Gallipoli Campaign

It was

not to be. When the war ended in triumph for Britain, India was denied its

promised reward. Instead of self-government, the British imposed the repressive

Rowlatt Act, which vested the Viceroy's government with extraordinary powers to

quell "sedition" against the Empire by silencing and censoring the

press, detaining political activists without trial, and arresting without a

warrant any individuals suspected of treason against the Empire. Public

protests against this draconian legislation were quelled ruthlessly. The worst

incident was the Jallianwallah Bagh massacre of April 1919, when

Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer ordered his troops to fire without warning on

15,000 unarmed and non-violent men, women and children demonstrating peacefully

in an enclosed garden in Amritsar, killing as many as 1,499 and wounding up to

1,137.

The fact

that Dyer was hailed as a hero by the British, who raised a handsome purse to

reward him for his deed, marked the final rupture between British imperialism

and its Indian subjects. Sir Rabindranath Tagore returned his knighthood to the

British in protest against "the helplessness of our position as British

subjects in India". He did not want a "badge of honour" in

"the incongruous context of humiliation".

With

British perfidy providing such a sour ending to the narrative of a war in which

India had given its all and been spurned in return, Indian nationalists felt

that the country had nothing to thank its soldiers for. They had merely gone

abroad to serve their foreign masters. Losing your life or limb in a foreign

war fought at the behest of your colonial rulers was an occupational hazard -

it did not qualify to be hailed as a form of national service.

British Library Image caption English and Indian soldiers of the

Lucknow Cavalry Brigade relaxing in a farmyard at HQ, 1915

Or so

most Indian nationalists thought, and they allowed the heroism of their compatriots

to be forgotten. When the world commemorated the 50th anniversary of the First

World War in 1964, there was scarcely a mention of India's soldiers anywhere,

least of all in India.

India's

absence from the commemorations, and its failure to honour the dead, were not a

major surprise. Nor was the lack of First World War memorials in the country:

the general feeling was that India, then freshly freed from the imperial yoke,

was ashamed of its soldiers' participation in a colonial war and saw nothing to

celebrate.

The

British, however, went ahead and commemorated the war by constructing the

triumphal arch known as India Gate in New Delhi. India Gate, built in 1931, is

a popular monument, visited by hundreds daily who have no idea that it

commemorates the Indian soldiers who lost their lives fighting in World War

One.

Thinkstock

India Gate memorial to WW1 soldiers, Delhi

In the

absence of a national war memorial, many Indians like myself see it as the only

venue to pay homage to those who have lost their lives in more recent

conflicts. I have stood there many times, on the anniversaries of wars with

China and Pakistan, and bowed my head without a thought for the men who died in

foreign fields a century ago.

As a

member of parliament, I twice raised the demand for a national war memorial

(after a visit to the hugely impressive Australian one in Canberra) and was

told there were no plans to construct one here. It was therefore personally

satisfying to me, and to many of my compatriots, when the government of India

announced in its budget for 2014-15 its intention finally to create a national

war memorial. We are not a terribly militaristic society, but for a nation that

has fought many wars and shed the blood of many heroes, and whose resolve may

yet be tested in conflicts to come, it seems odd that there is no memorial to

commemorate, honour and preserve the memories of those who have fought for

India.

The

centenary is finally forcing a rethink. Remarkable photographs have been

unearthed of Indian soldiers in Europe and the Middle East, and these are

enjoying a new lease of life online. Looking at them, I find it impossible not

to be moved - these young men, visibly so alien to their surroundings, some

about to head off for battle, others nursing terrible wounds. My favourite

picture is of a bearded and turbaned Indian soldier on horseback in Mesopotamia

in 1918, leaning over in his saddle to give his rations to a starving local

peasant girl. This spirit of compassion has been repeatedly expressed by Indian

peacekeeping units in United Nations operations since, from helping Lebanese

civilians in the Indian battalion's field hospital to treating the camels of

Somali nomads during the UN operation there. It embodies the ethos the Indian

solider brings to soldiering, whether at home or abroad.

IWM Indian cavalryman hands rations to starving Christian girls

For many

Indians, curiosity has overcome the fading colonial-era resentments of British

exploitation. We are beginning to see the soldiers of World War One as human

beings, who took the spirit of their country to battlefields abroad. The Centre

for Armed Forces Historical Research in Delhi is painstakingly working to

retrieve memorabilia of that era and reconstruct the forgotten story of the 1.3

million Indian soldiers who served in the First World War. Some of the letters

are unbearably poignant, especially those urging relatives back home not to

commit the folly of enlisting in this futile cause. Others hint at delights

officialdom frowned upon - some Indian soldiers' appreciative comments about

the receptivity of Frenchwomen to their attentions, for instance.

Astonishingly,

almost no fiction has emerged from or about the perspective of the Indian

troops. An exception is Mulk Raj Anand's Across the Black Waters, the tale of a

sepoy, Lalu, dispossessed from his land, fighting in a war he cannot

understand, only to return to his village to find he has lost everything and

everyone who mattered to him. The only other novel I have read about Indians in

the war, John Masters' The Ravi Lancers, inevitably is a Briton's account,

culminating in an Indian unit deciding to fight on in Europe "because we

gave our word to serve".

Dear Father...

Other

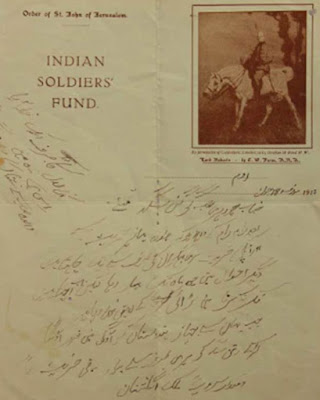

This

letter was written by an Indian soldier, Ram Singh (soldier in the Garhwal

Rifles) from the Kitchener Indian Hospital in Brighton, to his father. The

original letter (pictured) was censored and is held by Professor KC Yadav,

Gurgaon/India. The British Library has put the translations of a

number of letters from Indian soldiers online, including this one.

Ram Singh

acknowledges that letters are being censored. "We're not allowed to write

about the war," he writes. He complains how difficult the war was proving

to be. He writes that the information printed in the newspapers was lies,

implying that the stories of progress made in capturing ground were

exaggerated, when in fact they had "only captured 400 yards of

trenches".

But

Indian literature touched the war experience in one tragic tale. When the great

British poet Wilfred Owen (author of the greatest anti-war poem in the English

language, Dulce et Decorum Est) was to return to the front to give his life in

the futile First World War, he recited Tagore's Parting Words to his mother as

his last goodbye. When he was so tragically and pointlessly killed, Owen's

mother found Tagore's poem copied out in her son's hand in his diary:

When I go

from hence

let this

be my parting word,

that what

I have seen is unsurpassable.

I have

tasted of the hidden honey of this lotus

that

expands on the ocean of light,

and thus

am I blessed

---let

this be my parting word.

In this

playhouse of infinite forms

I have

had my play

and here

have I caught sight of him that is formless.

My whole

body and my limbs

have

thrilled with his touch who is beyond touch;

and if

the end comes here, let it come

- let

this be my parting word.

The

Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains war cemeteries in India, mostly

commemorating the Second World War rather than the First. The most famous

epitaph of them all is inscribed at the Kohima War Cemetery in North-East

India. It reads, "When you go home, tell them of us and say/ For your

tomorrow, we gave our today".

The

Indian soldiers who died in the First World War could make no such claim. They

gave their "todays" for someone else's "yesterdays". They

left behind orphans, but history has orphaned them as well. As Imperialism has

bitten the dust, it is recalled increasingly for its repression and racism, and

its soldiers, when not reviled, are largely regarded as having served an

unworthy cause.

But they

were men who did their duty, as they saw it. And they were Indians. It is a

matter of quiet satisfaction that their overdue rehabilitation has now begun.