BOOK EXCERPT

There is a fundamental discontinuity between the two cultures, writes Tony Joseph in his book ‘Early Indians’.

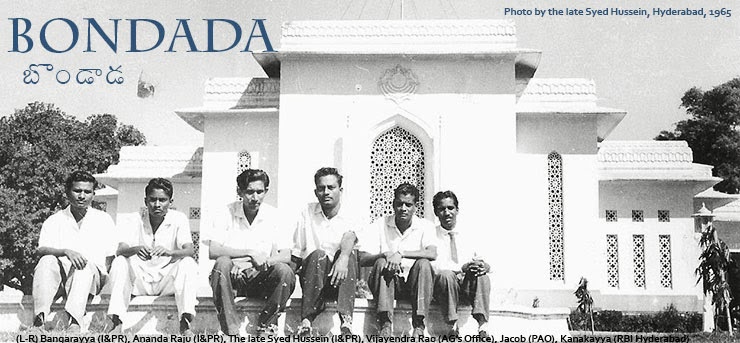

A seal depicting a unicorn at the Indian Museum, Kolkata | Wikimedia Commons (CC by SA 4.0)

Dec 25, 2018 · 08:30 am

Tony Joseph

It is possible, of course, that the cause for the decline of the Harappan Civilisation was not singular, but plural. The long drought may have drained the civilisation of its energy and also decimated its trade with Mesopotamia, which was going through its own crisis; the reigning ideology of the Harappan Civilisation may have collapsed as a result, leading to the disappearance of the symbols of power and commerce such as the ubiquitous seals and the script; there may have been internal rebellions; the Harappans may have taken the available option of moving to new fertile regions such as the Ganga valley and starting afresh rather than finding new ways of keeping the old system going; and the influx of a new wave of warrior-like migrants from the Eurasia Steppe might have been just the last straw that broke the system for good. But though the Harappan Civilisation may have gone into decline by around 1900 BCE, the people did not disappear and neither did the language nor all of the associated cultural beliefs and practices of the largest civilisation of its time.

This is because when the civilisation dimmed due to the long drought, the Harappans spread out, to both the east and the south, seeking new fertile land and carrying their language, culture and at least some of their practices with them.

The “Aryans” arrived around this time or a little later with a pastoralist lifestyle, new religious practices such as large sacrificial rituals, a warrior tradition and mastery over the horse and metallurgy.

The result was a mixing of populations and the formation of a new power elite that was dominant enough to ultimately force a language shift to Indo-European across northern India. Some of the beliefs and practices of the Harappans reshaped the religious ideology of the “Aryans” while some other practices would have continued as folk religion and culture at a more popular level.

In the south, the migrating Harappans would have found a more congenial atmosphere for their language and culture, partly because the “Aryans” had not yet reached peninsular India and, perhaps, partly because of the presence of earlier migrants who may have spread Dravidian languages.

In the language of genetics, the Harappans contributed to the formation of the Ancestral South Indians by moving south and mixing with the First Indians of peninsular India and also to the formation of the Ancestral North Indians by mixing with the incoming “Aryans”. Therefore, in many ways, they are the cultural glue that keeps India together – or the sauce on the pizza, to build on a metaphor that we used earlier.

That the newly dominant elite from the Steppe had a clear preference for a non-urban, mobile lifestyle may be part of the reason why India had to wait for more than a millennium after the Harappan Civilisation, for its “second urbanisation” that began after 500 BCE. As [David W] Anthony noted in The Horse, the Wheel and Language, the Yamnaya were a mobile, pastoral people who caused the near disappearance of settlement sites wherever they came to dominate.

When the Steppe migrants reached India, they would have come across a culture that already had its own myths, religious beliefs and practices and dominant language or languages, and was coping with a slowly unfolding disaster caused by the long drought. We do not yet know what different routes the people who called themselves “Aryans” may have taken, or how many different and competing groups there might have been.

What we do know is that the visible disconnect between the Harappan culture as revealed by its archaeological remains and the Indo-European culture as revealed by the Vedas – starting with the earliest composition, the Rigveda – reduces over time.

Here are a few examples of the early disconnect. The main gods and goddesses of the Rigveda – Indra, Agni, Varuna and the Asvins – find no representation in the vast repertoire of Harappan imagery. The converse is also true: the Rigveda is of no help in trying to interpret the dominant symbols and imagery of the Harappan culture – such as the ubiquitous seals that display a unicorn with what looks like a brazier or manger in front; the script; the Great Bath of Mohenjo-daro and its significance; and so on.

In fact, in one instance, the contrast between the Rigvedic principles and Harappan practice is quite striking. The Rigveda denounces “shishna-deva” (literal meaning: phallus god or phallus worshippers), while Harappan artefacts leave no one in doubt that phallus worship was part of its cultural repertoire. The archaeologist RS Bisht, who excavated the most visually stunning Harappan site in India at Dholavira, says there is clear evidence of deliberate destruction of phallic symbols and idols both in Dholavira and other sites after the civilisation declined. Book 7, 21.5 of the Rigveda says “may not the ‘shishna-deva’ approach our holy worship”, and Book 10, 99.3 describes how Indra slew them. Some authors have used “lustful demons” as the appropriate translation for “shishna-deva” in this context, but the literal meaning of the original text – and, of course, the animosity – is quite clear.

RS Bisht writes in his report on the Dholavira excavation: “At least six examples of free-standing columns were discovered from the excavations. These free-standing columns are tall...and with a top resembling a phallus or they are phallic in nature. That is why most of them were found in an intentionally damaged and smashed condition.”

~~~

Bisht is not a proponent of the idea that the Harappan Civilisation is not “Aryan” or “Vedic”. In fact, he believes that the kind of society that the Rigveda projects is close to what we find at the Harappan sites. However, he also admits that the Vedas looked down upon “shishna-devas” and that the lack of the horse in the Harappan Civilisation is a problem in identifying this civilisation as Vedic. Until the Harappan script is deciphered, he thinks, the dispute will continue.

The disconnect between the Harappan world and the world of the earliest Veda is apparent in less ideological and more mundane matters too. For example, the rest of the civilised world at the time knew of the Harappan Civilisation as Meluhha; the Harappans were involved in the politics of Mesopotamia, even to the extent of taking sides in their battles; and the economic relationship between Harappa and Mesopotamia was intimate enough for the Harappans to set up colonies in places such as the Oman peninsula to facilitate trading and even mining. But these complex, sophisticated trading activities and urban relationships do not find reflection in the early Vedic corpus. The world of the Rigveda and the world that is revealed by the material culture of Harappa seem two very different universes.

Excerpted with permission from Early Indians: The Story Of Our Ancestors And Where We Came From, Tony Joseph, Juggernaut.

Source:

scrollin