By Chris Plante

on

In 1996, The Simpsons passed The Flintstones as the longest running prime-time animated show. In the 30-year interim, the tenor of adult cartoons had shifted dramatically: The Simpsons was more caustic and puerile than The Flintstones, a shameless Stone Age remake of hit 1950s sitcom The Honeymooners. What had hardly changed was the creative process.

Like The Flintstones, The Simpsons relied on a large Los Angeles-based writer’s room, a coterie of directors, a squad of storyboard and design artists, and dozens of animators. The biggest change in production over three decades was simply geography; by 1996, The Simpsons had begun outsourcing the final stage of animation to a studio in South Korea.

A year after The Simpsons passed The Flintstones, South Park premiered on Comedy Central. If The Simpsons was a middle finger to the establishment, the animation of Trey Parker and Matt Stone was a burning bag of shit. It was cheap and fast to animate with paper cutouts, which allowed the show to comment on recent events. Cartoons at the time, requiring months of costly animation, needed to be comparably timeless in their story and humor, but South Park targeted the present.

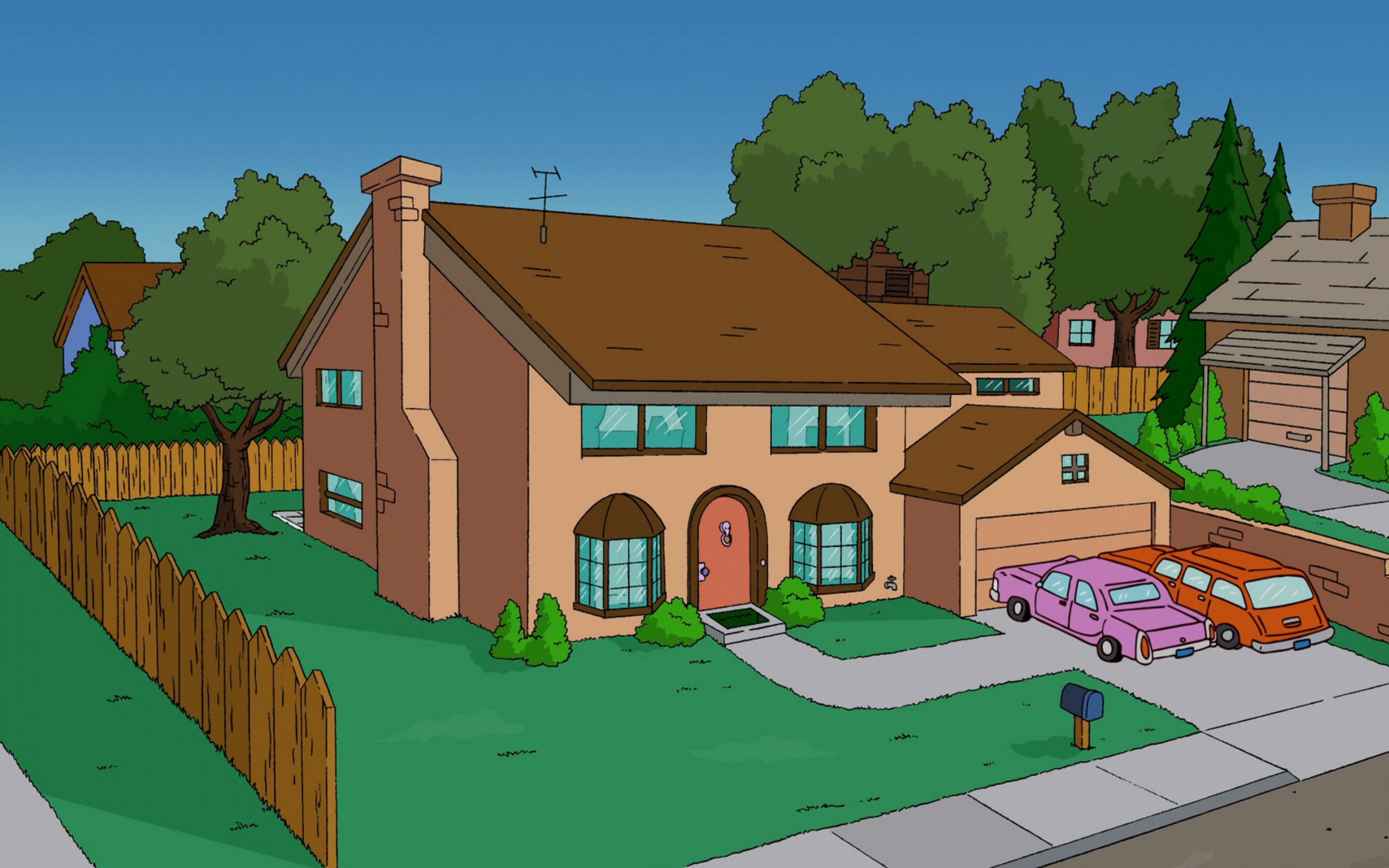

Thanks to computer animation and the internet, South Park, the shows of Adult Swim, and countless online-only animated shorts, like Homestar Runner, have made animation faster, rougher, and looser. But The Simpsons, to this day, embraces the formula of the past. While an episode of South Park can now be created in a single week by a lean team, The Simpsons has actually added roles and failsafes to its lengthy process. In the world of animated TV, The Simpsons may be the last of its kind, an expensive, high-touch, slow-paced production built on formulas dating back to Walt Disney and Hanna-Barbera.

The Simpsons is now in its 27th season. This is how an episode of the program is made, a detailed, meticulous look at a process that has its bedrock but builds upon it with the tools and lessons of the future.

Each writer brings a fleshed-out minute or so episode pitch, which they deliver with gusto to a room full of funny people. They laugh, take notes, then co-creator Matt Groening, executive producer James L. Brooks, and showrunner Al Jean — a portion of the braintrust from the earliest days — provide feedback.

In an essay on Splitsider about the writing process of seasons three through eight, former Simpsons writer and producer Bill Oakley described the pleasure of the retreats:

Like The Flintstones, The Simpsons relied on a large Los Angeles-based writer’s room, a coterie of directors, a squad of storyboard and design artists, and dozens of animators. The biggest change in production over three decades was simply geography; by 1996, The Simpsons had begun outsourcing the final stage of animation to a studio in South Korea.

A year after The Simpsons passed The Flintstones, South Park premiered on Comedy Central. If The Simpsons was a middle finger to the establishment, the animation of Trey Parker and Matt Stone was a burning bag of shit. It was cheap and fast to animate with paper cutouts, which allowed the show to comment on recent events. Cartoons at the time, requiring months of costly animation, needed to be comparably timeless in their story and humor, but South Park targeted the present.

Thanks to computer animation and the internet, South Park, the shows of Adult Swim, and countless online-only animated shorts, like Homestar Runner, have made animation faster, rougher, and looser. But The Simpsons, to this day, embraces the formula of the past. While an episode of South Park can now be created in a single week by a lean team, The Simpsons has actually added roles and failsafes to its lengthy process. In the world of animated TV, The Simpsons may be the last of its kind, an expensive, high-touch, slow-paced production built on formulas dating back to Walt Disney and Hanna-Barbera.

The Simpsons is now in its 27th season. This is how an episode of the program is made, a detailed, meticulous look at a process that has its bedrock but builds upon it with the tools and lessons of the future.

It begins with a pitch….

A few weeks before the warm Christmas of Southern California, the writers of The Simpsons — the longest-running sitcom in the US, starring everybody’s favorite family: Homer, Marge, Lisa, Baby Maggie, and their son Bart — take a retreat. The rest of the season, the team breaks scripts in the sterile writers' rooms of the Fox studio lot, but the creative process always began in a home or the big conference space of a nearby hotel.Each writer brings a fleshed-out minute or so episode pitch, which they deliver with gusto to a room full of funny people. They laugh, take notes, then co-creator Matt Groening, executive producer James L. Brooks, and showrunner Al Jean — a portion of the braintrust from the earliest days — provide feedback.

In an essay on Splitsider about the writing process of seasons three through eight, former Simpsons writer and producer Bill Oakley described the pleasure of the retreats:

"It was always a huge treat to see. You had no idea what George Meyer (for instance) was going to say, and suddenly it was like this fantastic Simpsons episode pouring out of his mouth that you never dreamed of. And it was like, wow, this is where this stuff comes from.

A lot of times people worked collaboratively, too. We would work with Conan, back and forth, and we’d exchange ideas and help polish them up. And so everybody would usually come with two, sometimes three ideas. You’d take fifteen minutes and you’d say your idea in front of everybody — all the writers, Jim Brooks, Matt Groening, Sam Simon when he was still there, and also the writers assistants who would be there taking notes on all this stuff."

Writing a draft

After receiving notes and some creative direction, an episode’s writer takes two weeks to pen a first draft. "Almost all of the writing is done here at the Fox [lot] in one of two rewrite rooms," says Al Jean, who at the time of the interview is deep into production of the show’s upcoming 27th season. "The two rooms was a change that came about around season nine. We split because we had enough writers, and we could get more done."

Getting more done with more tools and more hands is the throughline of the modern Simpsons production process. There are more people doing more jobs with more failsafes at a higher cost on The Simpsons than the majority of — if not all — animated television shows.

A writer has four to six weeks to complete rewrites. "We’ll continue to rework [the script] six or seven times before the table read," says Al Jean. "Jim and I will give notes. We rewrite it."

In those late night television commercials that promise to make everyone a screenwriter, the script is often called the blueprint of our favorite television shows and films, a term that implies an exacting, blessed, top level instruction which the rest of the dozens if not hundreds if not thousands of artists involved obey. That notion — as anyone who has seen a summer blockbuster or network sitcom can tell — is false. The script is vulnerable, malleable, and subject to constant scrutiny. There's a blueprint for animated shows, but it comes later. The completed draft is like a guide through the woods, ready to be supplemented, revised, or outright redrawn if need be.

A writer has four to six weeks to complete rewrites. "We’ll continue to rework [the script] six or seven times before the table read," says Al Jean. "Jim and I will give notes. We rewrite it."

In those late night television commercials that promise to make everyone a screenwriter, the script is often called the blueprint of our favorite television shows and films, a term that implies an exacting, blessed, top level instruction which the rest of the dozens if not hundreds if not thousands of artists involved obey. That notion — as anyone who has seen a summer blockbuster or network sitcom can tell — is false. The script is vulnerable, malleable, and subject to constant scrutiny. There's a blueprint for animated shows, but it comes later. The completed draft is like a guide through the woods, ready to be supplemented, revised, or outright redrawn if need be.

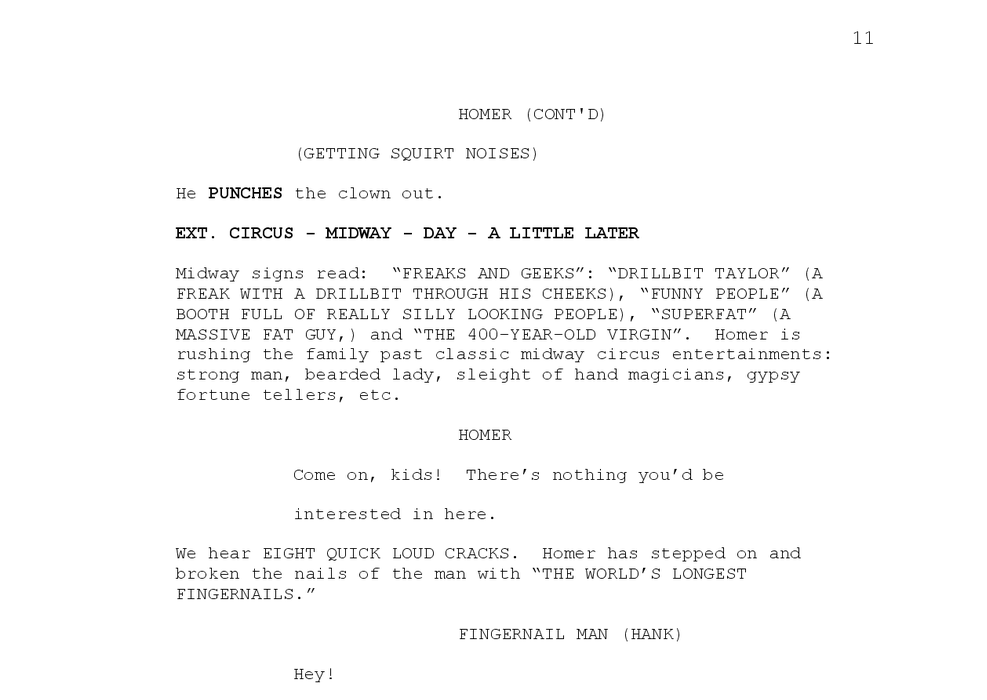

(An excerpt from Judd Apatow's The Simpsons script, The Daily Beast)

The table read

Each Thursday of production, the cast, producers, and writers meet for a table read of the latest script. Some of the cast attends the table read, others phone into the room. Occasionally, voice actor Chris Edgerly, who has handled "additional voices" for the show since 2011, will fill in for one of the leads. "It’s very unusual that they’re all at the table at the same time now," says Jean. "People’s schedules got busier, people actually moved out of Los Angeles. It’s the normal sort of entropy of life, you know."Despite being to hundreds of table reads, Al Jean still can’t get comfortable. He describes a critical setting in which the script is judged on its creative value, but also under the duress of external forces. A cell phone might go off or an actor might be fighting a cold, and the read's vibe shifts. "Last week," says Jean, "there was a truck backing up, that came in the middle, and that was distracting people. The table read is my number one unpleasant experience."

Voice recording

On the Monday following a table read, the cast performs the voice

recording, typically at the studio in LA. The actors and actresses

record on separate tracks, rather than together — a common method for

capturing voice-over. "It’s funny," says Jean. "I read a review in The AV Club

where they said about a certain show there was great interaction

between two people, and they never met. They didn’t record in the same

place. I’m glad it worked, but there was no physical connection."

Both Jean, who serves as story liaison throughout production of the series as a whole, and each episode’s director work in tandem to shepherd the script through the animation process.

Direction

As work transitions from script to animation, the episode is offered to a director, who, if they accept, is given ownership of production and animation responsibilities. "[The role is] sort of akin to a TV director who takes the script of a show and turns it into an episode," says Jean. "Except our director has to create everything. [... The director] takes the audio track, supervises the design, the motions, and what we call the acting of the animation, and [supervises] the whole visual aspect of [the episode]."Both Jean, who serves as story liaison throughout production of the series as a whole, and each episode’s director work in tandem to shepherd the script through the animation process.

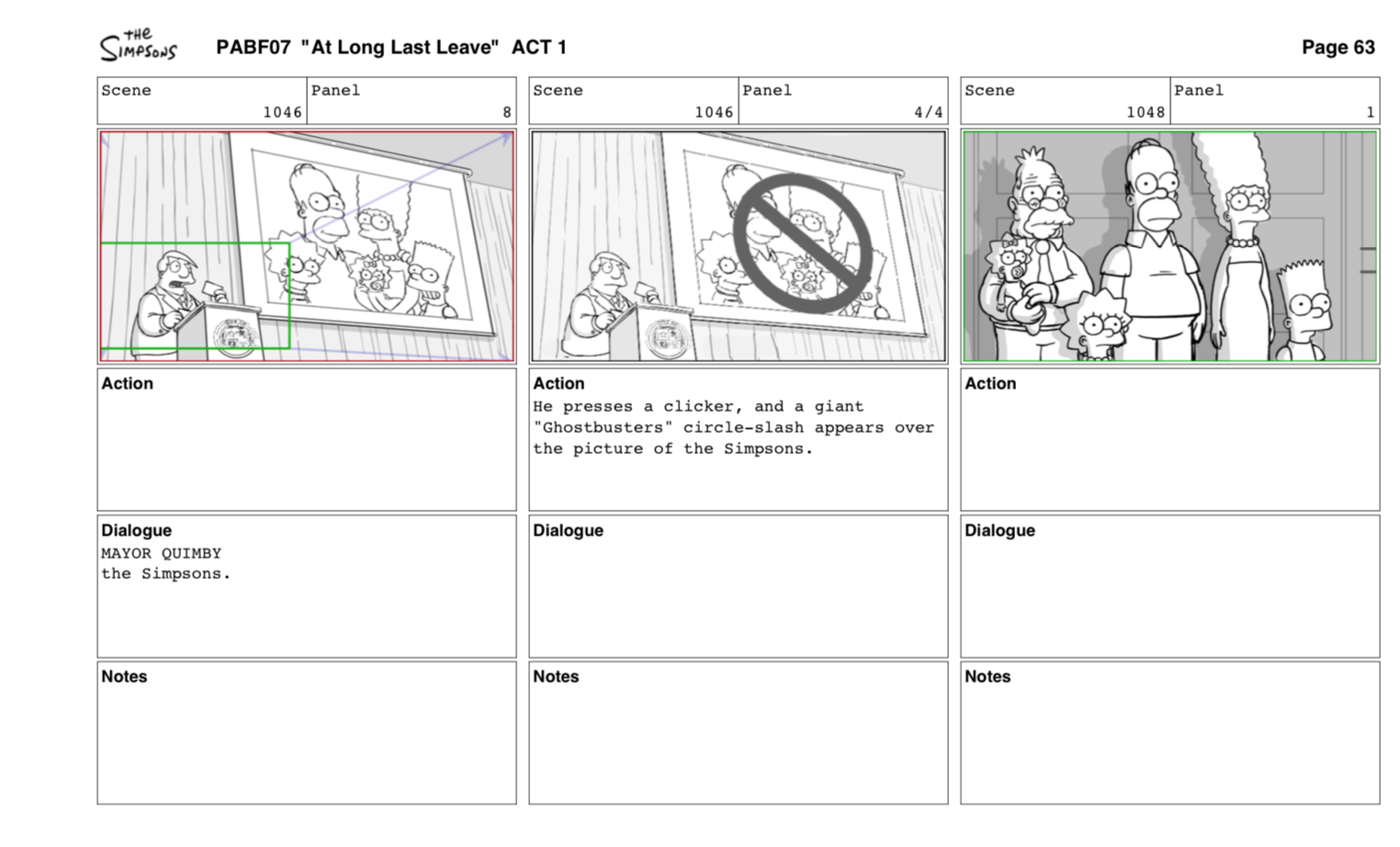

(The Simpsons storyboard)

Storyboard

According to veteran Simpsons storyboard artist Luis Escobar, the animation phase of a new season will begin between February and April, depending on the status of scripts and other production variables. Some animators have a hiatus between seasons; others periodically transition directly from one season to the next.An episode’s animation begins with storyboarding, a process that contains multiple steps, and ultimately produces the materials a South Korean animation studio named Akom will use to complete the episode.

"Our job," says Escobar, "is to do all the thinking, planning, and

[design] of the show. This is what it's going to eventually look like.

That’s what a storyboard is: just a blueprint of the episode."

An episode is assigned to a small group of initial storyboard artists at The Simpsons' work space in Southern California. According to an extensive series of posts on Escobar’s blog about the animation of the show, the board is reviewed, revised, and then sent to Fox for another round of notes. Alongside the storyboard, an additional squad of designers is assigned props, characters, and backgrounds unique to the episode, all of which undergo a similar series of internal and external drafts and reviews.

In early seasons, storyboarding was done entirely on paper. In mid-season, the show switched to animatics — a series of images paired with the voice track — that would be edited on tapes. Relatively recently, storyboards transitioned to digital, in which all of the art and audio is uploaded to an online hub accessible anywhere from computers and smart devices.

Jean says he can now edit audio from his phone instead of visiting an editing bay, and video effects can be made with a few digital tweaks, instead of requiring portions of the board to be entirely redrawn.

An episode is assigned to a small group of initial storyboard artists at The Simpsons' work space in Southern California. According to an extensive series of posts on Escobar’s blog about the animation of the show, the board is reviewed, revised, and then sent to Fox for another round of notes. Alongside the storyboard, an additional squad of designers is assigned props, characters, and backgrounds unique to the episode, all of which undergo a similar series of internal and external drafts and reviews.

In early seasons, storyboarding was done entirely on paper. In mid-season, the show switched to animatics — a series of images paired with the voice track — that would be edited on tapes. Relatively recently, storyboards transitioned to digital, in which all of the art and audio is uploaded to an online hub accessible anywhere from computers and smart devices.

Jean says he can now edit audio from his phone instead of visiting an editing bay, and video effects can be made with a few digital tweaks, instead of requiring portions of the board to be entirely redrawn.

(The Simpsons storyboard)

Story reel

The storyboard — revised from Fox’s notes and accompanied by the voice track — is screened to story reel artists, who are each assigned a portion of the episode. The work of the story reel artists, a mix of character and background animators, can range from polish to triage, depending on the storyboard's quality upon arrival. As Escobar explains, the reel artists add additional characters' poses, clean backgrounds, and incorporate notes from the director, who at this stage is refining the composition of the shots.As work is completed, the artists once again upload to a server, and the editor inserts the fleshed-out segments in place of their respective portions of the storyboard until the entire storyboard is replaced with a completed story reel.

The two phases sound quite similar, but they serve different functions. Where the storyboard is somewhere between a picture book and the flip book, the story reel visualization ideally plays like a barebones, black-and-white version of the actual episode.

Once the reel is ready, shareholders — Al Jean and the producers, writers, and episode director — meet at Fox for a screening. "It’s an interesting situation," writes Escobar, "because everyone in the room potentially knows all the jokes and how they should play out."

Shareholders take notes, discuss what works and doesn’t, then pitch additions or changes they’d like made. After a short break, the team reconvenes and watches the episode again, this time stopping and starting the reel to discuss how those changes will be incorporated, sketch rough stills of what the changes should look like, and nail down any other tweaks to be made by the storyboard revisionist.

Storyboard revisions

Storyboard revisionists get roughly two weeks to revise or outright create new scenes, following notes from the previous screening. Because hundreds of hours of animation and design have already gone into the storyboard, revisionists try to salvage parts from scenes that have been cut by repurposing them within the revisions.The revisionist must also make sure the changes flow with the rest of the story reel. On his blog, Escobar provides an example:

"Oh no! Homer needs to be on the other side of the room by the end of the sequence, but he no longer has that line that made him walk over there to begin with! How in blazes is he suppose to get to the other side to deliver his joke? CUT to a quick reaction shot of Bart or Marge. CUT back to Homer who is magically in the other side of the room. He must of walked over there while he was off screen. Problem solved."

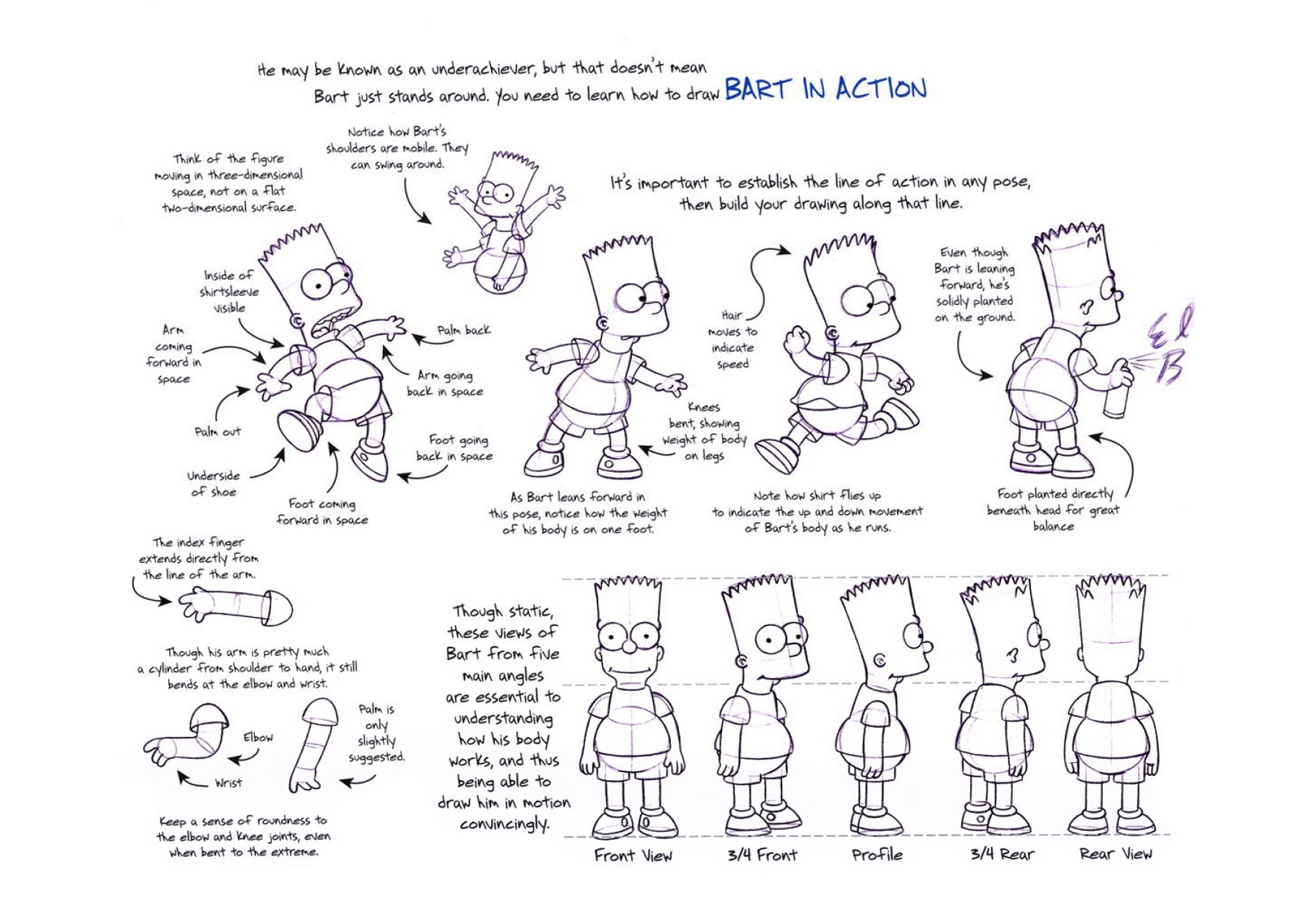

(Bart Simpson style sheet, Reddit)

Layout, he says, is the closest phase to what the layperson imagines animation to be — that classic image of a Disney cartoonist fanning paper back and forth, sketching characters into motion. At The Simpsons, layout is a digitized version of that method. Each animator — divided into character and background artists — uses Pencil Check Pro to animate roughly 15 scenes for an episode, making as accurate a depiction of the final product as possible. While storyboards are rough, layout is refined.

Characters are drawn to match a model sheet (above) — a guide of established poses and expressions for the show’s characters. Whenever Homer shouts with joy, the style sheet explains, his mouth opens in just this way.

Arguably the most important function of the layout artist is imbuing the static storyboard images with performance. When Homer cracks a beer, Lisa plays the saxophone, or Sideshow Bob steps on a rake, the layout artist decides precisely how that will look. In some capacity, they double as actors, using the storyboard and voiceover as direction, then emoting through the residents of Springfield as they feel fit.

The acting, the poses, the backgrounds, props, emotions — everything the story layout artists draw will be directly incorporated in the final "clean line" version of the episode animated by the studio in South Korea.

Along with performance, layout is when shots are framed, as they would be with a camera in the real world, exactly as they will appear in the finished episode.

Story layout is the longest and most detailed step, and can take anywhere from a month to a month and a half, depending on the complexity of the episode and whether or not other episodes are in production. "[It’s where the director has] the most control over what happens," says Escobar. "[As a storyboard artist,] I hear the words ‘I’ll take care of it in layout’ a lot from directors."

Layout

According to Escobar, few American animated shows still do the layout process, let alone do so in house.Layout, he says, is the closest phase to what the layperson imagines animation to be — that classic image of a Disney cartoonist fanning paper back and forth, sketching characters into motion. At The Simpsons, layout is a digitized version of that method. Each animator — divided into character and background artists — uses Pencil Check Pro to animate roughly 15 scenes for an episode, making as accurate a depiction of the final product as possible. While storyboards are rough, layout is refined.

Characters are drawn to match a model sheet (above) — a guide of established poses and expressions for the show’s characters. Whenever Homer shouts with joy, the style sheet explains, his mouth opens in just this way.

Arguably the most important function of the layout artist is imbuing the static storyboard images with performance. When Homer cracks a beer, Lisa plays the saxophone, or Sideshow Bob steps on a rake, the layout artist decides precisely how that will look. In some capacity, they double as actors, using the storyboard and voiceover as direction, then emoting through the residents of Springfield as they feel fit.

The acting, the poses, the backgrounds, props, emotions — everything the story layout artists draw will be directly incorporated in the final "clean line" version of the episode animated by the studio in South Korea.

Along with performance, layout is when shots are framed, as they would be with a camera in the real world, exactly as they will appear in the finished episode.

Story layout is the longest and most detailed step, and can take anywhere from a month to a month and a half, depending on the complexity of the episode and whether or not other episodes are in production. "[It’s where the director has] the most control over what happens," says Escobar. "[As a storyboard artist,] I hear the words ‘I’ll take care of it in layout’ a lot from directors."

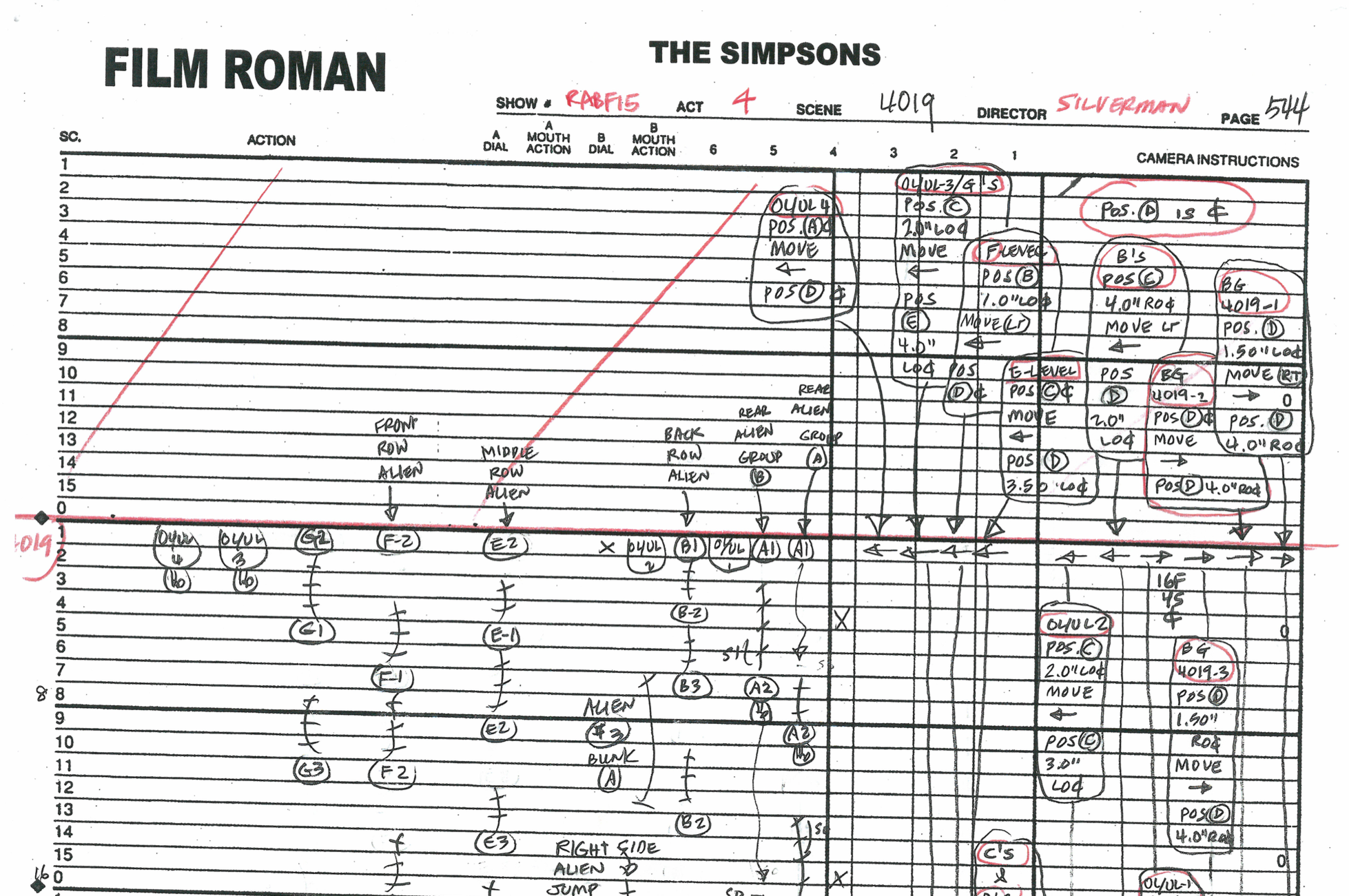

(The Simpsons exposure sheet)

The timer

As soon as a character layout artist finishes a scene, they deliver to the timer. A timer’s role is to write exposure sheets, the notes for Akom on how to interpret and apply the work of the story layout artist. If the layout artist's work is the wood for your new bookshelf, the exposure sheet is the instruction booklet. And like any furniture instructions, it's indecipherable to everyone but the experts.The role is called "timer," because in the past, the timer broke down all dialogue and animation, assigning tiny pieces to specific frames — or times — of the episode. Each line on the exposure sheet represents a frame or group of frames of film. To the right of each frame number, the timer writes what needs to be animated and how.

The Simpsons is animated at 24 frames per second — every second, 24 images appear on the screen — which is to say thousands of drawings can compose a single scene. To break down all of those drawings, the timer writes dialogue phonetically, and the established mouth shapes that match each sound, onto the exposure sheet. For example, Homer saying his own name would look something like Hhh-ooh-ohm-me-er-Si-im-ps-suh-hnn, each sound running down the page alongside their assigned frame numbers.

The timer would also include references to Homer’s character model sheet, and any specific accents or flourishes that needed to be made to his face or body. And the timers, of which there are two on The Simpsons' team, do this for every character in every scene.

(For those fascinated by the most unusual and overlooked position, former Simpsons director Chuck Sheetz created a tutorial on how to write classic exposure sheet, which should help you picture the timing in action.)

Escobar says that with the move to digital, character layout artists often "rough time" their scenes by creating a digital animatic, using the frames they've drawn to produce a very rough animation of a scene. The timer takes that animatic and documents the visuals onto the exposure sheet, adding any touches the animatic doesn’t include. Eye blinks, finger twiddles, fidgeting — there’s no detail too small for the timer to add to the exposure sheet, ensuring the team in LA maximum control over what the South Korean animation studio delivers.

Scene planning

If a scene is particularly complicated, it’s sent to Scene Planning, an internal team formed after The Simpsons Movie, that digitally animates elaborate scenes. The really flashy, fast-moving, large-scale scenes that feature a bevy of characters: they usually go through here."They're making sure there aren't any mistakes."

Checkers

Two checkers review everything — all of the character layout artwork, the exposure sheet, and the printed materials — and they make sure that every piece of art and line of direction matches on the exposure sheet."They’re basically the spell checkers," says Escobar. "They’re checking the grammar [of the animation]. They’re making sure that there aren’t any mistakes." If they find an inconsistency or a missing portion for artwork, they return to the director and get the error fixed.

Once every portion of the episode is checked and approved, it’s shipped to South Korea.

Akom

The role of Akom, a South Korean animation studio located west of Seoul, is to animate all of the frames between the drawings in the final reel delivered by the layout artists. Say the layout artists animated 20 frames for a 3-second scene. At 24 frames per second, the sequence is 72 frames long. The animation studio would need to do a clean line version of the original 20 frames and the 52 frames of animation between them. The process is called original equipment manufacturing; Akom is one of many OEM studios in its nation.According to a 2005 report by China Daily, Akom has handled the more or less final and unquestionably significant phase of animation on The Simpsons for nearly 25 years. At the time of China Daily’s report, roughly 120 animators and technicians translated the storyboard and layouts into the completed rough edit of an episode, a process that takes about three months, depending on the episode’s complexity and position within the season. The report cites OEM animators making a third of US counterparts, though it's unclear how pay has changed over the past decade.

Despite Akom's position in the animation wing of the show, Escobar couldn’t really speak to any other details about the work done at the animation studio. Escobar compared the aforementioned layout process in Los Angeles to the male animators of Disney’s golden era, but a paragraph in the China Daily report echoes Disney’s former band of women inkers and painters that put the finishing touches on the studio’s classics: "On one floor, a staff of mostly young women sit at computers as they scan animation cells, add colours and put the final technical touches to the show." Akom is the magic; the all-but-invisible twist that brings everything together.

Final review, retakes, and final edit

Akom ships a completed, full color version of the episode from South Korea back to the studio in Los Angeles, where it’s edited, then shown to the shareholders, who once again give notes for revisions. With the show approaching air date, this is where a few topical jokes are sometimes added.If there’s time, the notes are handled by Akom. If there isn’t time, the revisions are handled by the retakes division, a skeleton crew of two or three artists who can perform all functions of the animation process: storyboards, character layout, clean up, animation, and final timing.

"It gets really hectic," says Escobar, "because [retakes division has] to deal with the actual air dates. There have been situations or circumstances where the retakes finish the day or the night before [an episode] airs, that sort of thing where they’re like at work, actually cleaning the stuff up and coloring it."

Finally, an editor works with Al Jean to incorporate the retakes into the episode, does a final pass on the show’s colors, music is added — a process so substantive and distinct, it warrants an explainer unto its own — sound is mixed, the episode is wrapped, and it's sent to Fox where the new episodes air on Sunday nights.

The process doesn't so much start again, as it continues. As the production ramps, multiple episodes are in development at once, with every step of the process constantly overlapping. You understand why the writers — and everyone else involved — would need a retreat.

Looking back

When does Al Jean know an episode will make it safely through the process?"Usually at the mix," he says, "when everything’s all set. That’s pretty pleasant. The thing is, there’s always the potential that things are not coming together the way you expected. They can fall apart at the first audio assembly. They can fall apart at the animatic. They can fall apart in the color screening. You’re never really off the hook."

"The first episode ever done," Jean says, "was by someone who didn’t quite get the show. It needed a lot of rework. It was held back 'til maybe the last episode of the first season. It’s pretty well known it was very disappointing to everybody. Fortunately the second episode, 'Bart the Genius,' directed by David Silverman, was very good. The show was originally going to debut in the fall of ‘89, but because the first [episode] didn’t work, we decided to wait 'til Christmas so the episode directed by Silverman could be the first [airing in January, a little under a month after The Simpsons’ Christmas special, 'Simpsons Roasting on an Open Fire'].

We never, other than that, have taken a color and not aired it. We’ve done heavy rewrites sometimes at colors. We’ve never even thrown a script out after a [table] read. Maybe a couple of times we should’ve, but we never have."

Source: theverge

No comments:

Post a Comment