On Sunday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that it was “our duty to protect and respect the poor and Dalit people of our country”. For the Dalit families of Sodapur, these words come as cold comfort.

Written by Leena Misra | Sodapur | Updated: August 10, 2016 7:50 am

The Dalits who have relocated to Sodapur. (Express Photo)

Priyanka Meghwa was in Class X when she was forced to give up school in her village in Ghada. At her new home 15 km away, with nothing much to do, the 15-year-old spends time watching television. Ghar Ki Lakshmi Betiyaan, a soap celebrating daughters, and Sapne Suhane Ladakpan Ke are her favourite shows, she says.

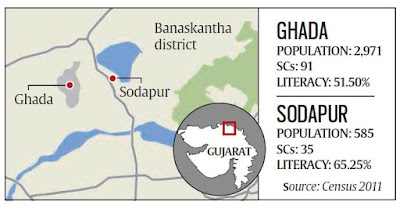

Two years ago, Priyanka’s family was among the 27 Dalit families who were forced to move to Sodapur from Ghada, both villages in the Deesa taluka of Banaskantha, the potato capital of Gujarat. All of them victims of untouchability, now refugees in their own state, which saw Dalit anger boiling over last month following the public flogging in Una of youths for skinning dead cattle.

On Sunday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that it was “our duty to protect and respect the poor and Dalit people of our country”. For the Dalit families of Sodapur, these words come as cold comfort.

At the entrance to Deesa, near the Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) building, a huge potato installation welcomes you. Deesa is also where Canadian food giant McCain sources its potatoes from. Large potato cold storages dot the way to Sodapur. On one side of the road that cuts through the village, stand rows of shacks covered with asbestos and lined with tarpaulin. This is the home of the Dalits from Ghada. Across the road, lives the rest of the village.

The practice of “extreme untouchability”, the Dalits claim, led to the murder of one of them nine years ago, forcing them to first sit in protest outside the local revenue official’s office for five years after which they came to Sodapur, leaving behind 100 bighas of land where they grew potatoes, castor, wheat, groundnut, bajra and rapeseed.

Priyanka’s sister Savita, 20, is married in Dhaneri village, which is a “happier village”, but says this is “home”, where her parents and siblings live.

Savita came home for her delivery and a week ago, gave birth to a daughter. The newborn lies on a charpoy, wrapped in a white cloth, flies hovering over. “I have to keep it completely wrapped even in this hot weather,” she says. The buffalo tied outside belongs to her grandmother Puriben who brought it from her brother’s house to source milk for Savita.

“All the girls gave up studying when we left Ghada. What do we do? Here, we have to take them across the busy road and fetch them back, which is not possible,” says Savita.

An orange cycle stands in the corner against a wall, one of the government freebies handed out to Savita’s brother, who freelances as a mason, at a Garib Kalyan Mela.

Even the boys gave up school. Dashrath, 18, dropped out in Class V, and is now a labourer, as his younger brother who dropped out in Class VII. “They didn’t let us sit together. They never played with us,” says Dashrath, about his upper-caste “darbar” (OBC) classmates in Ghada.

Talbiben weeps at the mention of Ramesh, her eldest son among five children. Her husband Devjibhai is too traumatised to put together the story of what happened.

Their 22-year-old son was “fairly educated” and worked as an insurance agent. But he had “dared” to enter a temple nine years ago, “breaking the rules” of Ghada. And paid for it. “They ran a tractor over him out of revenge. The police were also from their community and did not heed our pleas to consider it murder,” alleges Devjibhai.

Bhurabhai Parmar, the leader of this Dalit group, says, “We protested outside the mamlatdar’s office for five years. Finally, the mamlatdar and other government officials came to escort us here two years ago, but have not yet built us homes.”

Babarsinh Vaghela, sarpanch of Ghada at the time the Dalit families left, denies allegations of discrimination and describes Ramesh’s death as an accident.

“There was an accident in which the boy died. We tried hard to strike a compromise between the Dalits and the upper castes but they just did not listen. Finally, after the 12th-day ceremony of Ramesh’s death, they left the village,” he says.

“There is no untouchability in our village,” says Vaghela, who was the sarpanch till 2010.

But the Dalits allege that discrimination hit them every minute back in Ghada. “We could not go with uncovered heads before upper castes, could not wear pants, footwear or any gold. There were two buses to Deesa, at 9 am and 12 noon, from our village. If we got a seat and a darbar got on board in the packed bus, we had to vacate,” says Bhurabhai.

They had to send separate vessels for their children to have midday meals. “Our children were made to sit separately in the anganwadi, too,” he says.

The worst was when an upper-caste death occurred. “We would have to carry the body, collect the firewood and do all the rituals for 12 days for free. Ramesh opposed all these discriminatory practices. His murder was the last straw that provoked us to leave,” says Bhurabhai.

The few Ghada children who go to school in Sodapur are happier. Ashwin, who studies at the Bhakotar primary school in Class VIII, says everyone eats and studies together.

The Ghada Dalits are also grateful to the sarpanch of Sodapur, Amarsinh Dansinh Rajput, who got a resolution passed in the gram panchayat to let them stay.

“But only I know what I went through to get this done,” says Rajput, from the only Rajput family in Sodapur which has a large population of Brahmins, Patels and other OBCs.

“I needed five signatures in the sabha of nine members. I cajoled and convinced them to endorse it. But later, I got booked in two criminal cases and went to jail for 10 days. In one case, a Patel accused me of loot and I paid Rs 2.65 lakh for a compromise,” claims Rajput.

He continues to stand by the Dalits, who now total 35 families in this village. “There was a police inspector here who was a friend and he asked me if I could give some land to the Ghada Dalits and I agreed. I allotted them two bighas,” says Rajput.

All of the Sodapur resettlers have EPIC cards and all of them are registered under the Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGA) since 2014, but they say none of them have got any work or wages under it. “It is all on paper. We work as labourers — masons or farmers,” says Bhurabhai.

They are upset with the government for not building them homes, and point to half-built houses on one side of the land assigned to them. “They gave us only Rs 45,000 per home of which we spent Rs 10,000 on the landfill itself,” says Kaliben, one of the Dalits who moved to Sodapur.

Banaskantha collector Jenu Devan says, “They were given homes under the Dr Ambedkar Awas Yojana covering two installments, one of which was given. They will get the rest of the installment only after completion of their homes. This is as per the guidelines of the scheme.”

According to Devan, since the exodus was the result of an “accident” to Ramesh, it was not considered as “migration”. Migration is declared by the state government when conditions in the native place are not conducive to return and there is no scope of compromise with the upper castes.

While Devan says that one of the Dalit families returned to Ghada, sarpanch Vaghela claims that five families have come back from Sodapur.

Kaliben, meanwhile, settles down with three other women to mourn the drowning of her infant grandson in a water tank, a month ago. Their wails, and the mooing of the buffalo, rise over the everyday sounds in the basti.

Written by Leena Misra | Sodapur | Updated: August 10, 2016 7:50 am

Priyanka Meghwa was in Class X when she was forced to give up school in her village in Ghada. At her new home 15 km away, with nothing much to do, the 15-year-old spends time watching television. Ghar Ki Lakshmi Betiyaan, a soap celebrating daughters, and Sapne Suhane Ladakpan Ke are her favourite shows, she says.

Two years ago, Priyanka’s family was among the 27 Dalit families who were forced to move to Sodapur from Ghada, both villages in the Deesa taluka of Banaskantha, the potato capital of Gujarat. All of them victims of untouchability, now refugees in their own state, which saw Dalit anger boiling over last month following the public flogging in Una of youths for skinning dead cattle.

On Sunday, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that it was “our duty to protect and respect the poor and Dalit people of our country”. For the Dalit families of Sodapur, these words come as cold comfort.

At the entrance to Deesa, near the Agriculture Produce Market Committee (APMC) building, a huge potato installation welcomes you. Deesa is also where Canadian food giant McCain sources its potatoes from. Large potato cold storages dot the way to Sodapur. On one side of the road that cuts through the village, stand rows of shacks covered with asbestos and lined with tarpaulin. This is the home of the Dalits from Ghada. Across the road, lives the rest of the village.

The practice of “extreme untouchability”, the Dalits claim, led to the murder of one of them nine years ago, forcing them to first sit in protest outside the local revenue official’s office for five years after which they came to Sodapur, leaving behind 100 bighas of land where they grew potatoes, castor, wheat, groundnut, bajra and rapeseed.

Priyanka’s sister Savita, 20, is married in Dhaneri village, which is a “happier village”, but says this is “home”, where her parents and siblings live.

Savita came home for her delivery and a week ago, gave birth to a daughter. The newborn lies on a charpoy, wrapped in a white cloth, flies hovering over. “I have to keep it completely wrapped even in this hot weather,” she says. The buffalo tied outside belongs to her grandmother Puriben who brought it from her brother’s house to source milk for Savita.

“All the girls gave up studying when we left Ghada. What do we do? Here, we have to take them across the busy road and fetch them back, which is not possible,” says Savita.

An orange cycle stands in the corner against a wall, one of the government freebies handed out to Savita’s brother, who freelances as a mason, at a Garib Kalyan Mela.

Even the boys gave up school. Dashrath, 18, dropped out in Class V, and is now a labourer, as his younger brother who dropped out in Class VII. “They didn’t let us sit together. They never played with us,” says Dashrath, about his upper-caste “darbar” (OBC) classmates in Ghada.

Talbiben weeps at the mention of Ramesh, her eldest son among five children. Her husband Devjibhai is too traumatised to put together the story of what happened.

Their 22-year-old son was “fairly educated” and worked as an insurance agent. But he had “dared” to enter a temple nine years ago, “breaking the rules” of Ghada. And paid for it. “They ran a tractor over him out of revenge. The police were also from their community and did not heed our pleas to consider it murder,” alleges Devjibhai.

Bhurabhai Parmar, the leader of this Dalit group, says, “We protested outside the mamlatdar’s office for five years. Finally, the mamlatdar and other government officials came to escort us here two years ago, but have not yet built us homes.”

Babarsinh Vaghela, sarpanch of Ghada at the time the Dalit families left, denies allegations of discrimination and describes Ramesh’s death as an accident.

“There was an accident in which the boy died. We tried hard to strike a compromise between the Dalits and the upper castes but they just did not listen. Finally, after the 12th-day ceremony of Ramesh’s death, they left the village,” he says.

“There is no untouchability in our village,” says Vaghela, who was the sarpanch till 2010.

But the Dalits allege that discrimination hit them every minute back in Ghada. “We could not go with uncovered heads before upper castes, could not wear pants, footwear or any gold. There were two buses to Deesa, at 9 am and 12 noon, from our village. If we got a seat and a darbar got on board in the packed bus, we had to vacate,” says Bhurabhai.

They had to send separate vessels for their children to have midday meals. “Our children were made to sit separately in the anganwadi, too,” he says.

The worst was when an upper-caste death occurred. “We would have to carry the body, collect the firewood and do all the rituals for 12 days for free. Ramesh opposed all these discriminatory practices. His murder was the last straw that provoked us to leave,” says Bhurabhai.

The few Ghada children who go to school in Sodapur are happier. Ashwin, who studies at the Bhakotar primary school in Class VIII, says everyone eats and studies together.

The Ghada Dalits are also grateful to the sarpanch of Sodapur, Amarsinh Dansinh Rajput, who got a resolution passed in the gram panchayat to let them stay.

“But only I know what I went through to get this done,” says Rajput, from the only Rajput family in Sodapur which has a large population of Brahmins, Patels and other OBCs.

“I needed five signatures in the sabha of nine members. I cajoled and convinced them to endorse it. But later, I got booked in two criminal cases and went to jail for 10 days. In one case, a Patel accused me of loot and I paid Rs 2.65 lakh for a compromise,” claims Rajput.

He continues to stand by the Dalits, who now total 35 families in this village. “There was a police inspector here who was a friend and he asked me if I could give some land to the Ghada Dalits and I agreed. I allotted them two bighas,” says Rajput.

All of the Sodapur resettlers have EPIC cards and all of them are registered under the Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MNREGA) since 2014, but they say none of them have got any work or wages under it. “It is all on paper. We work as labourers — masons or farmers,” says Bhurabhai.

They are upset with the government for not building them homes, and point to half-built houses on one side of the land assigned to them. “They gave us only Rs 45,000 per home of which we spent Rs 10,000 on the landfill itself,” says Kaliben, one of the Dalits who moved to Sodapur.

Banaskantha collector Jenu Devan says, “They were given homes under the Dr Ambedkar Awas Yojana covering two installments, one of which was given. They will get the rest of the installment only after completion of their homes. This is as per the guidelines of the scheme.”

According to Devan, since the exodus was the result of an “accident” to Ramesh, it was not considered as “migration”. Migration is declared by the state government when conditions in the native place are not conducive to return and there is no scope of compromise with the upper castes.

While Devan says that one of the Dalit families returned to Ghada, sarpanch Vaghela claims that five families have come back from Sodapur.

Kaliben, meanwhile, settles down with three other women to mourn the drowning of her infant grandson in a water tank, a month ago. Their wails, and the mooing of the buffalo, rise over the everyday sounds in the basti.

Source: indianexpress

No comments:

Post a Comment