By Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay on 09/05/2017

A

fortnightly column reflecting on chapters of India’s political

past that are relevant today.

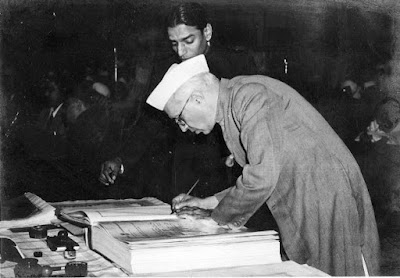

Jawaharlal

Nehru signing the Indian constitution. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

In recent

years, the relationship between the executive and judiciary has not been at its

cordial best and allegations of judicial overreach have flowed unremittingly.

On several occasions, the highest members of the judiciary have

also expressed disappointment over the executive’s failure to address

issues hampering legal benches. Trust, confidence and deference, initially the

foundation of this relationship between the vital pillars of the state, is

regrettably conspicuous in its absence.

Several

members of this government – and the previous one(s) – nurse a grouse that the

judiciary habitually appropriates powers of executive. This allegation finds

support among even non-partisan legal luminaries as several judgements bear

witness to the judiciary’s tendency to overstep judicial activism.

By

straying beyond the proverbial Lakshman rekha, the judiciary provided

justification to the executive’s purpose of ‘subduing’ it. Blatant attempts to

undermine the judiciary, in turn a threat to Indian democracy’s basic

character, unfortunately has majority approval. Ironically, this government is

pursuing the aim first articulated by an ideological adversary – the

self-proclaimed leftist in Indira Gandhi’s government, Mohan Kumaramangalam.

In 1973,

stung by judiciary stymieing his prime minister’s intention of amending the

constitution at will, Kumaramangalam, the minister for steel, went beyond his

ministerial brief and propounded the concept of “committed judiciary”. The

sordid episode of supersession of eminent judges was a result of such thinking.

Since then, several attempts were made to ensure compliance of the judiciary

and get judges to accept harmonising between legislature and executive as their

primary task. Few politicians, especially when part of establishment, openly

advocate necessity for a “committed judiciary”, but there is no dearth of those

who covet it.

However,

post-independence, it was not always like this. Jawaharlal Nehru had

reservations on the judiciary’s interpretation of the constitution – this even

led to the first amendment on the freedom of expression – but he displayed

ample respect.

The

script began going awry exactly half a century ago, in 1967, when the Supreme

Court delivered its verdict in the Golaknath case. The bitter

confrontation between the judiciary and executive in its wake continued for

more than six years till the judgement in the Kesavananda Bharati case

in 1973. This judgement thereafter has provided protection to the basic

character of the constitution.

Between

February 1967 and April 1973, the government made a concerted bid to ensure the

parliament had uncontrolled powers to amend or abridge any part of the constitution,

including the fundamental rights. Recalling this chapter in governance and

relationship between the judiciary and executive becomes imperative because of

the return of one-party dominance and similarities in the personalities of

Gandhi and Narendra Modi. However, this narrative has to be framed within the

political timeline of the period.

The Golaknath

verdict was delivered within days of the verdict of the fourth Lok Sabha

elections that renewed Gandhi’s tenure as the prime minister. Yet, despite a majority

in the parliament, the Congress lost power in several states. Besides forming

coalition governments in several states, and the weakening political and moral

authority of Congress, Gandhi was caught in a bitter power struggle within her

party. But she was intent on forging her own destiny. To secure her objective,

Gandhi sought unrivalled power and an amended constitution. She also sought a

favourable judiciary.

The Golaknath

case stemmed from the family (of the same name) challenging acquisition of their

farmlands in Punjab under land ceiling laws. The case predated her tenure but

became a constitutional landmark. It triggered political upheaval because the

family challenged acquisition of their land on grounds it violated their

fundamental right to hold and acquire property and practice any profession.

The

Golaknaths also contended attachment of lands denied them equality and

equal protection as constitutionally guaranteed. The case raised the vital

question: can fundamental rights be amended or not? The 11-judge bench in this

case examined its own five-judge verdict in a previous case (Sankari Prasad

vs Union of India) when the court ruled parliament had the right to amend

any part of the constitution.

Eventually,

the apex court reversed its previous verdict and now declared that parliament

did not have the right to amend fundamental rights, in part or in whole. The

court also ruled that despite it being the parliament’s duty to enforce the

directive principles of state policy, this could not be done by altering

fundamental rights. Gandhi viewed the ruling as an obstacle in her attempt to

secure absolute political control.

In July

1969, two years and five months after the Golaknath verdict, as part of

her political offensive, Gandhi nationalised 14 banks. The decision was

promptly challenged and in less than seven months the Supreme Court struck down

the decision. A few months later, Gandhi abolished privy purses but this

too was termed illegal by Supreme Court in December 1970.

Concluding

that by now the people were on her side, Gandhi dissolved the parliament and

hurried into India’s first snap poll in March 1971. Though she decimated the

grand alliance and secured a huge victory, the three successive unfavourable

judicial verdicts still stung her.

Bent on

humbling the judiciary, Gandhi moved a series of constitutional amendments

providing government with untrammelled right to limit, alter or even abolish

fundamental rights. An American journalist reported that she was “moving to

become the most powerful woman in the world” and “under cover of India war

preparations” she was establishing a “socialist dictatorship on the pattern of

Soviet Union.”

The

Statesman‘s

editorial was more ominous, “The implications are breath-taking. Parliament now

has the power to deny the seven freedoms, abolish constitutional remedies

available to citizens and to change the federal character of the Union.”

Of the

three constitutional amendment bills – the 24th, 25th and 26th – the first

enabled to override the Golaknath judgement, while the other two circumvented

judicial verdicts on bank nationalisation and privy purses. As part of the

Twenty-fourth Amendment, Articles 13 and 368 of the constitution were amended.

While the former waived off applicability of the article to amendments made in

the latter, Article 368, in its amended form, provided power to the parliament

to amend any part of the constitution.

With the

amendments, the government circumvented the hurdles posed by the three

‘troublesome’ verdicts. But Gandhi’s troubles with the judiciary did not end as

chief of a mutt in Kerala challenged the state government’s order restricting

his power to manage properties of the institution. The wheels of justice were

turning slowly but as subsequent events demonstrated, the grind was exceedingly

fine.

Kesavananda

Bharati vs State of Kerala, as the case is called in the annals of Indian judicial history,

got its name from the pontiff of the mutt (though he never met his counsel Nana

Palkhivala) and also went to the apex court. Because this case too related to

the scope of the power of amendment of the constitution under Article 368, it

was heard by a 13-judge bench, undoubtedly to give it greater authority than

the 11-judge bench in the Golaknath case. In April 1973, when the apex

court pronounced its judgement, the bench was split vertically with seven

judges in majority and six against, just as the previous case was decided by a

six-five majority.

The Kesavananda

Bharati judgement overruled the Golaknath verdict and gave back to

the parliament the right to amend the constitution provided its “basic

structure” was not altered. For the government this was half a victory – it won

the basic case, but still did not have unrestrained powers to ‘tamper’ with the

constitution. The verdict had takeaways for both sides but the most important

victory was undoubtedly for the object of the legal clash – the Indian

constitution and the right to alter its fundamental spirit.

Unambiguously,

the court ruled that the “basic structure” was sacrosanct. This judgement has

since given strength to the constitution and provides basis for the faith that

return of one-party dominance will not undermine the Indian constitutional

system.

Yet, half

a century after the Golaknath case triggered a determined bid by the

government of the day to change laws as it willed, the entire episode stands as

a reminder of the future dangers. The importance of the Kesavananda Bharati

judgement notwithstanding, it left ambiguity regarding the “basic structure”,

which was not defined.

The

abstraction of the concept notwithstanding, events over the six-year period

ensured Supreme Court’s emergence as one of the most powerful judicial

institutions in the world. These proceedings settled that the parliament is the

creature of the constitution and not the other way around. But this conclusion

cannot be taken for granted in contemporary India. When institutions are

subverted, does it take much time for consensus on ideas to be cast away?

Nilanjan

Mukhopadhyay is a Delhi-based writer and journalist, and the author of Narendra Modi: The Man, The Times

and Sikhs: The Untold Agony of 1984. He tweets @NilanjanUdwin

Source:

thewire