The WikiLeaks founder is out to settle a score with Hillary Clinton and reassert himself as a player on the world stage, says BuzzFeed News special correspondent James Ball, who worked for Assange at WikiLeaks.

posted on

Oct. 23, 2016, at 4:11 p.m.

BuzzFeed

Special Correspondent

Carl Court

/ Getty Images

On 29 November 2010, then US

secretary of state Hillary Clinton stepped out in front of reporters to condemn

the release of classified documents by WikiLeaks and five major news

organisations the previous day.

WikiLeaks’ release, she said, “puts

people’s lives in danger”, “threatens our national security”, and “undermines

our efforts to work with other countries”.

“Releasing them poses real risks to

real people,” she noted, adding, “We are taking aggressive steps to hold

responsible those who stole this information.”

Julian Assange watched that message

on a television in the corner of a living room in Ellingham Hall, a stately

home in rural Norfolk, around 120 miles away from London.

I was sitting around 8ft away from

him as he did so, the room’s antique furniture and rugs strewn with laptops,

cables, and the mess of a tiny organisation orchestrating the world’s biggest

news story.

Minutes later, the roar of a

military jet sounded sharply overhead. I looked around the room and could see

everyone thinking the same thing, but no one wanting to say it. Surely not.

Surely? Of course, the jet passed harmlessly overhead – Ellingham Hall is not

far from a Royal Air Force base – but such was the pressure, the adrenaline,

and the paranoia in the room around Assange at that time that nothing felt

impossible.

Spending those few months at such

close proximity to Assange and his confidants, and experiencing first-hand the

pressures exerted on those there, have given me a particular insight into how

WikiLeaks has become what it is today.

To an outsider, the WikiLeaks of

2016 looks totally unrelated to the WikiLeaks of 2010. Then it was a darling of

many of the liberal left, working with some of the world’s most respected

newspapers and exposing the truth behind drone killing, civilian deaths in

Afghanistan and Iraq, and surveillance

of top UN officials.

Now it is the darling of the

alt-right, revealing hacked emails seemingly to influence a presidential

contest, claiming the US election is “rigged”, and descending into conspiracy.

Just this week on Twitter, it described the deaths by natural causes of two of

its supporters as a “bloody year for

WikiLeaks”, and warned of media outlets “controlled by”

members of the Rothschild family – a common anti-Semitic trope.

The questions asked about the

organisation and its leader are often the wrong ones: How has WikiLeaks changed

so much? Is Julian Assange the catspaw of Vladimir Putin? Is WikiLeaks

endorsing a president candidate who has been described as racist, misogynistic,

xenophobic, and more?

These questions miss a broader

truth: Neither Assange nor WikiLeaks (and the two are virtually one and the

same thing) have changed – the world they operate in has. WikiLeaks is in many

ways the same bold, reckless, paranoid creation that once it was, but how that

manifests, and who cheers it on, has changed.

Julian Assange in the grounds

of Ellingham Hall in December 2010. Carl Court / AFP / Getty Images

The cable release

Clinton’s condemnation of WikiLeaks

and its partners’ release of classified cables was a simple requirement of her

job. Even had she privately been an ardent admirer of the site – which seems

unlikely – doing anything other than strongly condemning the leak was

nonetheless never an option.

That’s not how it felt to anyone

inside WikiLeaks at that moment, though. It was an anxiety-inducing time.

WikiLeaks was the subject of every cable TV discussion, every newspaper front

page, and press packs swarmed the gates of every address even tenuously

connected to the site. Commentators called for arrest, deportation, rendition,

or even assassination

of Assange and his associates.

At the same time, WikiLeaks was

having its payment accounts frozen

by Visa and Mastercard, Amazon

Web Services pulled hosting support, and Assange was jailed for a week in

the UK (before being bailed) on unrelated charges relating to alleged sexual

offences in Sweden.

Inside WikiLeaks, a tiny

organisation with only a few hundred thousand dollars in the bank, such

pressure felt immense. Most of the handful of people within came from a

left-wing activist background, many were young and inexperienced, and few had

much trust of the US government – especially after months of reading cables of

US mistakes and overreactions in the Afghan and Iraq war logs, often with

tragic consequences.

How might the US react, or

overreact, this time? WikiLeaks was afraid of legal or extralegal consequences

against Assange or other staff. WikiLeakers were angry at US corporations

creating a financial blockade against the organisation with no court ruling or

judgments – just a press

statement from a US senator.

And the figurehead of this whole

response was none other than Hillary Clinton. For Assange, to an extent, this

is personal.

Hillary Clinton in 2010,

giving remarks condemning WikiLeaks’ release of classified embassy cables. Win Mcnamee / Getty

Images

In the room

It’s unfair, or at least an

oversimplification, to say that Assange is anti-American. He would say he

supports the American people but believes its government, its politics, and its

corporations are corrupt.

A result of this is that he doesn’t

see the world in the way many Americans do, and has no intrinsic aversion to

Putin or other strongmen with questionable democratic credentials on the world

stage.

This shows in some of his

supporters. A few days after Assange arrived with me and a few others at

Ellingham Hall, an older man, introduced to us as “Adam”, turned up. Assange

had invited independent freelance journalists from around the world to the

country house to see cables relating to their country – usually no more than a

few thousand at a time.

“Adam” was different: He

immediately asked for everything relating to Russia, eastern Europe, and Israel

– and got it, more than 100,000 documents in all. A few stray comments of his

about “Jews” prompted a few concerns on my part, dismissed quickly by another

WikiLeaker – “don’t be silly… He’s Jewish himself, isn’t he?”

A short while later, I learned

“Adam”’s real identity, or at least the name he most often uses: He was Israel

Shamir, a known pro-Kremlin and anti-Semitic writer. He had been photographed

leaving the internal ministry of Belarus, and a free speech charity was

concerned this meant the country’s dictator had access to the cables and their

information on opposition groups in the country.

Assange showed no concern at these

allegations, dismissing and ignoring them until the media required a response.

Assange simply denied Shamir had ever had access to any documents.

This was untrue, Assange knew it was untrue, and I knew it was untrue — it was me, at Assange’s instructions, who gave them to him. A few days later, a reporter at a Russian publication wrote to WikiLeaks.

“I really can’t understand why

Wikileaks is just cooperating with the magazine Russian reporter which never

had a record of even slightly critising [sic] the Russian government,” they

wrote.

“I contacted the person responsible for contacts with Wikileaks in Russia (Israel Shamir) but he told me we could not look at the cables ourselves and requested money which is not very convenient for us (not because of money but because we would like to go through the files as well).”

Anti-Semitism never seemed a major

part of Assange’s agenda – I never heard him say a remark I caught as

problematic in this way – but it was something he was happy to conveniently ignore

in others. Support for Russia or its strongmen eastern European allies was much

the same: tolerable for those who otherwise are allies of WikiLeaks and do as

Assange says.

WikiLeaks has never had a problem

with Russia: not then, not now.

A supporter of Julian Assange

stands outside Ecuador’s London embassy at a protest in 2012. Oli Scarff / Getty Images

A certain resemblance

Assange is routinely either so

lionised by supporters or demonised by detractors that his real character is

lost entirely.

Far from the laptop-obsessed autist

he’s often seen as, he’s a charismatic speaker with an easy ability to dominate

a room or a conversation. He may have little interest in listening to those

around, but he can tell whether or not he has your attention and change his

manner to capture it. He has, time and again, proven to be a savvy media

manipulator, marching the mainstream media up the hill and down again to often

damp-squib press conferences. His technical skills are not in doubt.

What’s often underestimated is his

gift for bullshit. Assange can, and does, routinely tell obvious lies:

WikiLeaks has deep and involved procedures; WikiLeaks was founded by a group of

12 activists, primarily from China; Israel Shamir never had cables; we have

received information that [insert name of WikiLeaks critic] has ties to US

intelligence.

At times, these lies are harmless

and brilliant. When, on the day the state cables launched, WikiLeaks’ site

wasn’t ready (we hadn’t even written the introductory text), the site was kept

offline after a short DDoS attack, with Assange tweeting that the site was

under an unprecedentedly huge attack.

Six hours later, when we were done,

all eyes were looking: What was so bad in the cables that someone was working

so hard to keep the site offline? The dramatic flourish worked, but other lies

were dumb and damaging – and quickly eroded any kind of trust for those trying

to work closely with him.

Redaction – possibly one of the

clearest apparent changes between 2010 and 2016 WikiLeaks – became one of these

trust issues. For Assange, redacting releases was essentially an issue of

expediency: It would remove an attack line from the Pentagon and state, and

keep media partners onside. For media outlets, it was the only responsible way

to release such sensitive information.

These days, WikiLeaks routinely

publishes information without redaction, and seemingly with only minimal

pre-vetting. This is merely a change in expediency: There are no longer

newspaper partners to keep onside. The results are a partial vindication for both

sides – while it’s hard to dispute that some

of WikiLeaks’

publication of private data has been needlessly reckless and invasive,

there remains no evidence of any direct harm coming to someone as a result of a

WikiLeaks release.

Conversely, Assange often trusts

strangers more than those he knows well: He dislikes taking advice, he dislikes

anyone else having a power base, and he dislikes being challenged – especially

by women. He runs his own show his own way, and won’t delegate. He’s happy to

play on the conspiratorial urges of others, with little sign as to whether or

not he believes them himself.

There are few limits to how far

Assange will go to try to control those around him. Those working at WikiLeaks

– a radical transparency organisation based on the idea that all power must be

accountable – were asked to sign a sweeping nondisclosure agreement covering

all conversations, conduct, and material, with Assange having sole power over

disclosure. The penalty for noncompliance was £12 million.

I refused to sign the document,

which was sprung on me on what was supposed to be a short trip to a country

house used by WikiLeaks. The others present – all of whom had signed without

reading – then alternately pressured, cajoled, persuaded, charmed and pestered

me to sign it, alone and in groups, until well past 4am.

Given how remote the house was,

there was no prospect of leaving. I stayed the night, only to be woken very

early by Assange, sitting on my bed, prodding me in the face with a stuffed

giraffe, immediately once again pressuring me to sign. It was two hours later

before I could get Assange off the bed so I could (finally) get some pants on,

and many hours more until I managed to leave the house without signing the

ridiculous contract. An apologetic staffer present for the farce later admitted

they’d been under orders to “psychologically pressure” me until I signed.

And once you have fallen foul of

Assange — challenged him too openly, criticised him in public, not toed the

line loyally enough — you are done. There is no such thing as honest

disagreement, no such thing as a loyal opposition differing on a policy or

political stance.

To criticise Assange is to be a

careerist, to sell your soul for power or advantage, to be a spy or an

informer. To save readers a Google search or two, he would tell you I was in

WikiLeaks as an “intern” for a period of “weeks”, and during that time acted as

a mole for The Guardian, stole documents, and had potential ties

to MI5. Compared to some who’ve criticised Assange, I got off fairly lightly.

Those who have faced the greatest

torments are, of course, the two women who accused Assange of sexual offences

in Sweden in the summer of 2010. The details of what happened over those few

days remain a matter for the Swedish justice system, not speculation, but

having seen and heard Assange and those around him discuss the case, having

read out the court documents, and having followed the extradition case in the

UK all the way to the supreme court, I can say it is a real, complicated sexual

assault and rape case. It is no CIA smear, and it relates to Assange’s role at

WikiLeaks only in that his work there is how they met.

Assange’s decision – and it was a

decision – to elide his Swedish case with any possible US prosecution was a

cynical one. It led many to support his cause alongside those of Chelsea

Manning or Edward Snowden. And yet it is not: It is more difficult, not easier,

to extradite Assange to the US from Sweden than from the UK, should Washington

even wish to do so.

Assange coming to believe his own

spin may be what’s been behind six years of effective imprisonment for him. No

one is keeping him in the Ecuadorian embassy – where he has fallen

out with his hosts – but himself, and a fear of losing face. But the women

who began the case have lost at least as much, becoming for months and years

two of the most hated figures on the internet, smeared as “whores”, “CIA spies”,

and more. They will never get their time back.

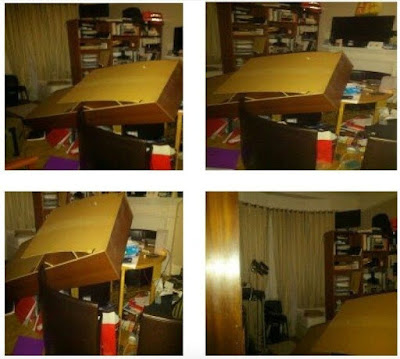

Four photos of Julian

Assange’s room in Ecuador’s London embassy, prepared for an internal report

following an incident in which officials believe Assange toppled a bookshelf. Ecuadorian government

report / Via buzzfeed.com

How it

ends

All of

this is the cocktail of ingredients that produces 2016’s incarnation of

WikiLeaks. Julian Assange mistrusts the US government, dislikes Hillary

Clinton, and has spent years trapped in a small embassy flat in west London, in

declining physical and psychological health, monitored minute-by-minute in

reports filed by

his wary Ecuadorian hosts.

Assange

would not, in my view, ever knowingly be a willing tool of the Russian state:

If Putin came and gave him a set of orders, they’d be ignored. But if an

anonymous or pseudonymous group came offering anti-Clinton leaks, they’d have

found a host happy not to ask too many awkward questions: He’s set up almost

perfectly to post them and push for them to have the biggest impact they can.

The poet

Humbert Wolfe wrote, “You cannot hope to bribe or twist / (thank God!) the

British journalist. / But, seeing what the man will do / unbribed, there’s no

occasion to.”

Such is

Russia’s good fortune with Assange. If it is indeed Russia behind the leaks, as

US intelligence has reported, he will need no underhanded

deals or motives to do roughly as they’d hope. He would do that of his own free

will.

The question

is whether Assange will end up disappointed. Assange believes WikiLeaks was a

primary driver of the Arab Spring, which led to major uprisings in around a

dozen countries. This is the stage on which Assange believes he plays — the

equal of a world leader, still the biggest story in the world.

For a

time, he was. While the extent of WikiLeaks’ role in the Arab Spring remains a

matter for debate, Assange was at the forefront of an information revelation.

His attempts to regain the spotlight in the meantime have largely failed.

WikiLeaks

has republished public information as if a leak; published hacks obtained by

Anonymous and Lulzsec for only moderate impact; and email caches of private

intelligence companies of much less significance than what went before. Even

Assange’s attempt to aid Edward Snowden was largely botched, leaving the

whistleblower stranded in a Moscow airport for weeks. In recent weeks, Snowden

has publicly clashed with Assange over the latter’s

handling of the Democratic National Committee leaks.

@Snowden

Opportunism won't earn you a pardon from Clinton & curation is not

censorship of ruling party cash flows https://t.co/4FeygfPynk

—

WikiLeaks (@wikileaks)

Assange’s

approach has taken WikiLeaks from the most powerful and connected force of a

new journalistic era to a back-bedroom operation run at the tolerance (or

otherwise) of Ecuador’s government. This is his shot at reclaiming the world

stage, and settling a score with Hillary Clinton as he does so.

Assange

is a gifted public speaker with a talent for playing the media struggling with

an inability to scale up and professionalise his operation, to take advice, a

man whose mission was often left on a backburner in his efforts to demonise his

opponents.

These are

traits often ascribed to Donald Trump, the main beneficiary of WikiLeaks’

activities through the reaction, and its modern-day champion during

presidential debates. Those traits have left Assange a four-year resident of a

Harrods hamper–laden single room in a London embassy.

It remains to be seen what they’ll do for Donald Trump.

James

Ball is a special correspondent for BuzzFeed News and is based in London.

Source: buzzfeed