Food

and culture

The

Vedas refer to about 50 animals deemed fit for sacrifice and, by inference, for

eating.

Wellcome

Library, London

Apr

10, 2017 · 12:30 pm

Mrinal

Pande

Folks

with infantile minds keep laying down laws for what is dharma and the true path

and what is holy or unholy, says Matsyendranath (the guru of Gorakhnath who

laid the foundations for the Nath sect in North India), in his seminal treatise

Akulveer Tantra (78-87). One doesn’t know if his present-day follower,

the newly incumbent chief minister of Uttar Pradesh, Adityanath, would agree,

but according to Guru Matsyendranath, to gain true knowledge is to rise above

various petty rules and definitions propagated in the name of dharma. Kaulopanishad,

the shorter but even more intense treatise of the Kaul Siddhanta (yes,

the Kashmiri surname derives from it), goes a step further and says the only

thing that is forbidden is badmouthing others (lok ninda). Real self-knowledge,

adhyatma, means observing no fasting, feasting or rules thereof, and no desire

for founding a sect. All are created equal and one who realises this becomes

truly free (mukt).

The

present-day political dispensation, blinded as it is by its politicised and

reductive vision of things, including vegetarianism, would do well to look

towards the true Indian culture foreign to its lunatic fringes, and one that

they are unable to absorb. My mother’s teacher, the great scholar Hazari Prasad

Dwivedi, once used a wonderful term from the Shakta Tantra for a true

understanding of history. He called it shav sadhana, a term used by a tantrik

sadhaka to explain to him that to gain true knowledge (siddhi), one needs to

find and straddle a dead body at a masan (cremation ground, a spot where all

lives have been reduced to ash) and then meditate, shutting out everything

around him. It is a long and tedious process during which evil forces try their

best to distract the seeker with half-truths, but if he can remain detached and

focused, at some point the head of the corpse will turn completely around and

as it faces the constant sadhaka, address and explain the quintessential

wisdom, setting all his queries at rest. Picture this: pure knowledge being

passed on through an inert form with the head at an angle of 360 degrees,

offering no attachment either to the old or the new, the traditional or the

practised forms of life. This, Hazari Prasad Dwivedi writes, is knowledge that

sets one free.

It is

only against this rather long philosophical context (the Sanskrit for

philosophy is darshan, meaning to see) that the highly incendiary subject of

the long history of meat eating in India can be understood properly.

History

of meat-eating

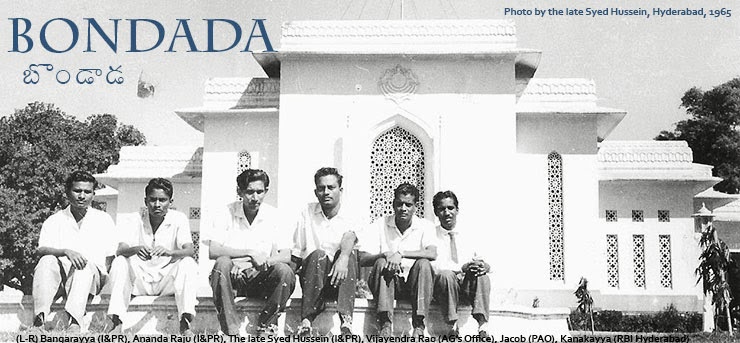

There is

enough historical evidence by now that Indians since the days of the Indus

Valley have indulged in dishes made with meat and poultry: zebu cattle (humped

cattle), gaur (Indian bison), sheep, goat, turtle, ghariyal (a crocodile-like

reptile), fish fowl and game. The Vedas refer to more than 250 animals

of whom about 50 were deemed fit to be sacrificed and, by inference, for

eating. The marketplace had various stalls for vendors of different kinds of

meat: gogataka (cattle), arabika (sheep), shookarika (swine), nagarika (deer)

and shakuntika (fowl). There were even separate vends for selling alligator and

tortoise meat (giddabuddaka). The Rigveda describes horses, buffaloes,

rams and goats as sacrificial animals. The 162nd hymn of the Rigveda describes

the elaborate horse sacrifice performed by emperors. Different Vedic gods are

said to have different preferences for animal meat. Thus Agni likes bulls and

barren cows, Rudra likes red cows, Vishnu prefers a dwarf ox, while Indra likes

a bull with droopy horns with a mark on its head, and Pushan a black cow. The Brahmanas

that were compiled later specify that for special guests, a fattened ox or goat

must be sacrificed. The Taittireeya Upanishad praises the sacrifice of a

hundred bulls by the sage Agasthya. And the grammarian Panini even coined a new

adjective, goghna (killing of a cow), for the guests to be thus honoured.

The meat,

we learn, was mostly roasted on spits or boiled in vats. The Brihadaranyaka

Upanishad has reference to meat cooked with rice. Also the Ramayana,

where during their sojourn in the Dandakaranya forest, Rama, Lakshmana and Sita

are said to have relished such rice (with meat and vegetables). It is called

mamsambhutdana. In the palace at Ayodhya, during the sacrifices performed by

king Dashratha, the recipes described are far more exotic with acid fruit

juices being added to mutton, pork, chicken and peacock meat and cloves,

caraway seeds and masur dal also being added to various dishes. The Mahabharata

has references to rice cooked with minced meat (pistaudana) and picnics where

various kinds of roasted game and game birds were served. Buffalo meat was

fried in ghee with rock salt, fruit juices, powdered black pepper, asafetida

(hingu) and caraway seeds, and served garnished with radishes, pomegranate

seeds and lemons.

Then come

the Buddhist Jatakas and Brahtsamhita (6th Century CE) that

maintain the list of non-vegetarian food items, adding some more species. All

in all, meat till then appears to have been deemed a nourishing food. It is

even recommended by the famed physician Charaka for the lean, the very hard

working and those convalescing from a long illness. The Jains, of course,

remained totally averse to devouring any form of life. But the Buddha did not

forbid the eating of meat if offered as alms to Buddhist bhikkus, provided the

killing should not have happened in the presence of the monks. It was the

responsibility of the giver of the alms to ensure this.

No

inhibitions down south

Down

south, the inhibitions against eating meat and fish are rare. In the earliest

writings on food dating back to 300 CE, pepper (kari) is described as the main

spice for flavouring meat. Fried meat had three names and meat boiled with

tamarind and pepper was called pulingari. It was occasionally ground to make a

sort of pasty relish. Kapilar, the famous Brahmin priest of the Sangam age,

speaks with a certain relish of consuming meat and liquor. Old Tamil has four

terms for beef: valluram, shushiyam, shuttiraichi and padithiram. There were 15

names for pork, a special favourite, we learn, among the wives of traders in

the coastal region. There are also references to wild boar, rabbits and deer

being hunted with hunting dogs. Captured boars were fattened with rice flour

and kept away from the female to make their flesh tastier. Among more exotic

meats were porcupines (a favourite of the Kuruvars) and fried snails (favoured

by the Mallars). Down south, there was also no taboo on eating domestic fowl

(kozhi). Fish and prawns were greatly relished all along the coastal region, so

much so that the word for fish, meen, also entered the lexicon of Sanskrit as

the north learnt to relish this fruit of the seas.

Contrary

to prevalent notions, the Ayurvedacharyas did not deem meat as avoidable. The Sushrut

Samhita compiled by the physician sage Sushruta lists eight kinds of meats.

The Manasollas, a treatise ascribed to the 13th century king Someshwara,

similarly gives pride of place to the chapter on food entitled Annabhoga. It

refers to nuggets of liver roasted or fried and then served with yogurt or a

decoction of black mustard, to pigs roasted whole with rock salt and pepper

with a dash of lemon and served carved in strips resembling palm leaves.

There are

no fewer than three great artistic works in Hindi that, like the panels of a

tryptich, portray the hellish vision of things for this century: Yashpal’s Jhootha

Sach, Rahi Masoom Raza’s Adha Gaon and Bhisham Sahni’s Tamas.

The Yogi’s Raj had only to make its entrance to mime what fiction had already

imagined.

We

welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.

Source:

scrollin