The Dalit icon had said that continued marginalisation would lead to class struggle and noted that fraternity was integral to nation-building.

Image

credit: Sam Panthaky/AFP

India celebrated its 70th Independence Day on August 15 against the backdrop of widespread agitations by Dalits over the increased boldness of cow protection vigilante groups in Gujarat.

But these protests are not just about gaurakshaks, they are another instance of a community rallying against discrimination in society. As one of the most recognisable Dalit icons, BR Ambedkar was aware of this and stated multiple times in the Constituent Assembly Debates that unless this disenfranchisement could be curbed, such sentiments would threaten the stability of the document with which he is most associated – India’s Constitution.

Some people may assume that as the “father of the Constitution”, Ambedkar is its sole author, but the document on the basis of which India is governed was actually the product of the Constituent Assembly. The Assembly comprised leading figures from the Congress party and members of other communities who sat and discussed the provisions of the Constitution, and were assisted in this capacity by various committees.

Though he had other roles, as the head of the drafting committee, Ambedkar was in charge of making sure that decisions made by the Assembly and the various committees were translated into the final draft.

Despite the hegemony of the Congress, the Assembly was remarkably diverse – the party actively sought out non-members (like Ambedkar) and allowed its own members to vote freely. Any given issue elicited a host of conflicting stands and the members would hammer out their differences until they came as close as possible to a unanimous decision.

The idea of India

Reading the proceedings of the Assembly (of which the Debates are just a part) thus provides a more textural understanding to the Constitution and acts as a window to the kind of India its founding fathers wished to create.

Ambedkar, unsurprisingly, is one of the prominent speakers in the Debates. One of his standout speeches was on the eve of the Constitution’s adoption. He spoke on the conditions that he felt would benecessary to ensure that the Constitution would last and that democracy in India would be achieved in reality.

Ambedkar felt that “democracy in India was only a top-dressing on an Indian soil which is essentially undemocratic” and pointed out that ensuring political democracy would be insufficient without creating social democracy.

Granting political equality through voting, without simultaneously ensuring social and economic equality would be creating an unsustainable set of contradictions, he felt. This is why he included Liberty, Equality and Fraternity in the preamble and viewed them as inseparable.

What is paramount

Ambedkar valued fraternity as the most integral part of nation-building and felt that without it, liberty and equality “will be no deeper than coats of paint”. He dubbed castes as “anti-national” as they created social divisions in social life. He must have spoken from personal experience when he said that the historical monopoly of political power reduced many to “beasts of burden” and “beasts of prey” in a manner that sapped their “significance of life”.

He surmised that these subjugated peoples were “tired of being governed” and were impatient for self-governance. He felt that the longer they were denied this urge for self-actualisation, the more likely they were to resort to a class struggle. And in his view, nothing threatened the health of the Constitution more than societal divisions.

However, fraternity is extremely hard to create because unlike liberty and equality, it cannot be secured through laws. One way to achieve it could be to delve more into the founding of our nation as a society. This would mean school lessons that are not a drab timeline of events, well-researched biographies (not hagiographies) as well as plays, movies and stories.

Educating India

Knowledge of the founding of a nation is invariably accompanied by literacy in the core principles that the founders fought for and that the nation holds dear. Sadly, the average constitutional literacy of Indians is a fraction of that of citizens in other countries, such as the United States.

Most Americans are taught about the founding fathers, the Federalist Papers and the Bill of Rights at an early age. Aside from giving the average American a working knowledge of the rights granted to him or her, this education has come to shape public discourse quite remarkably. Almost all civil-rights movements in the US, be it those for women, African-Americans, or more recently, the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender community, draw their legitimacy from the language of the Declaration of Independence.

The remarkable response to the Broadway play Hamilton – a musical about Alexander Hamilton, one of the founding fathers of the US – shows that the American polity recognises the worth of Constitutional history. However, in India these subjects have historically been handled dryly in Civics classes and a system of rote regurgitation prevents these lessons from having any permanency in children’s minds.

The long road to equality

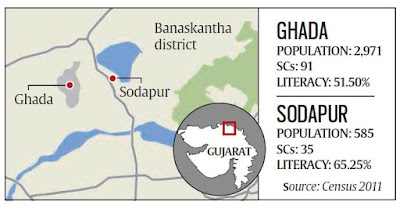

The flogging of Dalit youth in Gujarat’s Una last month for skinning the carcass of a dead cow and the resultant protests show that India is still a long way off the vision of equality held by our founding fathers. But the longer that certain sections of the society – be it Dalits or Kashmiris – continue to feel marginalised, the greater the threat to the Constitution.

It is to their credit that the protestors in Gujarat followed another tenet of Ambedkar and used constitutional methods to express their dissent. But unless such sections of society feel more included, stability will be difficult to sustain – as Abraham Lincoln said, a house divided against itself cannot stand.

It is, therefore, time to inculcate the fraternity Ambedkar spoke of by rediscovering our constitutional history, both inside and outside schools. Not only would this help give Indians a better knowledge of their rights but also a sense of the idea of India. This could be the umbrella under which Indians discover a sense of fraternity – and if nothing else, create public literacy in the rich language of constitutionalism that people looking to reform India can capitalise on.

Madhav Chandavarkar is a research associate at Takshashila Institution, an independent, non-partisan think tank and school of public policy.

We welcome your comments at letters@scroll.in.

Source: scrollin