Dinesh D’Souza and the shame of immigrant self-hatred

By

February 20, 2015

I have two shameful family secrets. The first is that when I was growing up, almost all gatherings of my extended clan would include buckets and buckets of Kentucky Fried Chicken, a staple of our diet. The second and more serious source of self-mortification is that some of my kin—almost all of whom hail from rural India—sometimes vent anti-black racism.These two focal points of embarrassment merged when I was 19 and went on a KFC run with a cousin I will call Amandeep. As our car glided into the parking lot, we saw a black family exiting the fast food joint. “Boy, black people sure love fried chicken,” Amandeep muttered. The comment angered as it baffled me: He clearly couldn’t see the irony of stereotyping black culture while heading for one of our regular KFC pick-ups. It was actually one of Amandeep’s more benign remarks. On other occasions he made Charles Murray-like forays into questions of black genetic inheritance and propensity toward crime.

I wish Amandeep’s racial theories were an anomaly, but he’s far from alone among South Asian immigrants. Anti-black racism, I’ve often thought, is one of the more unwholesome manifestations of assimilation. If blacks are near the bottom of the perceived racial hierarchy across North America, some enterprising immigrants find it useful to step on blacks as a way of climbing higher.

Racism among South Asians has some peculiar qualities; it’s not so much hatred of the other but the hatred of the almost-the-same, akin to a sibling rivalry. At the heart of this sort of immigrant racism is the desire to differentiate oneself from the group one could easily be identified with. As it happens, Amandeep is one of the most dark-hued members of my family. When he was small, his nickname in India was “kala” (Punjabi for black). I’ve sometimes thought that some discomfort at being labeled black contributed to his racial fixations.

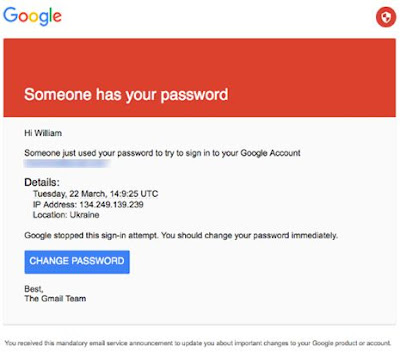

Dinesh D’Souza, the right-wing provocateur whose history of incendiary racial comments stretches to his undergraduate days in the early 1980s, provides an interesting case study for the intersection of immigrant upward mobility and racism. D’Souza grabbed attention this week for a tweet about President Obama taking a selfie: “YOU CAN TAKE THE BOY OUT OF THE GHETTO...Watch this vulgar man show his stuff, while America cowers in embarrassment.”

YOU CAN TAKE THE BOY OUT OF THE GHETTO...Watch this vulgar man show his stuff, while America cowers in embarrassment pic.twitter.com/C9yLG4QoOK — dineshdsouza

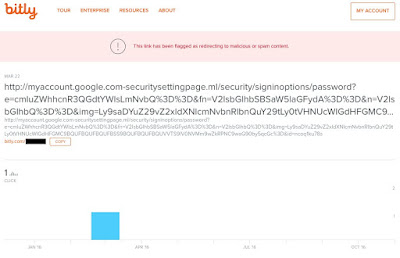

This tweet was only the latest in a long career of racist hijinks. As student editor of the right-wing newspaper the Dartmouth Review, he published racially charged material. One D’Souza-edited article discussed affirmative action in Amos 'n' Andy dialect. “Now we be comin’ to Dartmut and be over our ‘fros in studies, but we still not be graduatin’ Phi Beta Kappa," the article read. In his 1995 book The End of Racism, D’Souza argued that “the old discrimination” has declined and been replaced by “rational discrimination” based “on accurate group generalizations.” During the Obama years, D’Souza has specialized in writing books and producing documentaries suggesting the President is motivated by anti-colonial hatred of Western civilization. After pleading guilty to campaign finance violations last year, D’Souza remains unbowed, casting himself as the victim of a political witch-hunt by the Obama administration. Amid this flurry, D’Souza continues to tweet ugliness like this and this.

undefined — AdamSerwer

Obama forcefully asserts his position on Beheading pic.twitter.com/QbVbvE582d — dineshdsouza

It’s tempting to dismiss D’Souza as an outlier. He’s aligned with the right-wing of the Republican party, while the vast majority of American South Asians identify as Democrats. Still, anyone who spends time among South Asians will recognize the popular currency of attitudes like D’Souza's. Moreover, D’Souza indicates a wider problem, given that one of the Republican Party's most prominent Islamophobic voices is Louisana Governor Bobby Jindal, a South Asian. D’Souza's racism and Jindal's xenophobia find a more muted parallel in the career of South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley, whose advancement includes suppressing public references to her Sikh heritage and being presented by her campaign as a “proud Christian woman.” The careers of D’Souza, Jindal, and Haley carry an implicit message: Racial minorities can advance in the GOP by erasing their ethnic identity and/or attacking other minorities.

D’Souza’s racism makes sense if we view it as part of his long effort to succeed in a right-wing milieu that is both anti-Indian and anti-black. Within that context, D’Souza has given saliency to anti-black racism to compensate for a potentially embarrassing background as a Mumbai-born immigrant. Is D’Souza sincere in his beliefs or simply an intellectual mercenary? It’s impossible to know for sure. What can be said with certainty is that as an Indian willing to voice anti-black sentiment, D’Souza has carved out a lucrative niche for himself, enjoying a national audience from the time he was an undergraduate.

D’Souza’s mentor at the Dartmouth Review was the English professor Jeffrey Hart, who also served as a senior editor at National Review. The college paper was founded in Hart’s living room, and he was the de facto career counselor who guided D’Souza and other Dartmouth alumni into the world of right-wing journalism. Hart's work from the '70s onward offers a clear philosophical foundation and tactical guide to D'Souza's writings during Obama's presidency.

In 1975, Hart published a startling review of Jean Raspail’s xenophobic novel The Camp of Saints, a didactic tract warning of the dangers of mass immigration from India and other poor countries. The novel celebrates the heroism of a ragtag band of right-wing heroes (including a tank commander and a duke) who wage a sniper campaign against the refugees. “In this novel Raspail brings his reader to the surprising conclusion that killing a million or so starving refugees from India would be a supreme act of individual sanity and cultural health,” Hart wrote in a National Review rave (September 26, 1975) that compared the book to modern masterpieces by James Joyce and D. H. Lawrence. “Raspail is to genocide," Hart continued, "what Lawrence was to sex."

Hart’s praise of Raspail’s novel might seem at odds with his sponsorship of D’Souza’s career. But even in reviewing The Camp of Saints, Hart distinguishes between good immigrants who assimilate to white culture and the refugee horde who must be exterminated. As Hart notes, Raspail’s novel features a character named Hamadura, “a very black Indian” who “has lived in France and become completely assimilated by Western Civilization.” As the character notes: “Being white isn’t really a question of color. It’s a whole mental outlook.” In his prize student D’Souza, Hart found his own version of Hamadura: a “very black Indian” who has the mental outlook of a white conservative.

In its stark division of the world between the West and the threatening chaos of the non-white world, Hart’s review was an exercise in imperial nostalgia that D’Souza later echoed when he complained that Obama suffers from a Kenyan, “anticolonialist” mindset. (Others have followed D'Souza in attacking Obama with that phrase. The latest: Rudy Giuliani.)

Hart's brand of imperial nostalgia pervades the wider National Review conservatism that shaped D’Souza’s worldview. A foundational text in this weltanschauung is James Burnham’s Suicide of the West (1964), which D’Souza cited in his book What’s So Great About America (2002). Thematically, Burnham pioneered many of the themes D’Souza has expanded upon in books like The Roots of Obama’s Rage (2010) and Obama’s America (2012): the insidiousness of white liberal guilt in disarming the West, the underappreciated virtues of imperialism and manifest destiny, the need to affirm the unequivocal cultural superiority of Western civilization. Among the founding editors of National Review, Burnham was second only to William F. Buckley in importance. His book is key to understanding the contradictions of D’Souza's role in the conservative movement as a non-white advocate for “the West.”

As with Jeffrey Hart, Burnham combined a scorn for the great mass of Indians and African Americans with a belief that a few non-whites might be of some service to the West. At one point Burnham offers an anecdote about the folly of liberals who overestimate the intelligence of South Asians and "Africans":

“I recall an evening not long ago that I spent with one of the country’s most distinguished historians, who is a liberal à outrance. As the night wore on, he got somewhat more tight than was his habit; and at one point he remarked, more to his fifth gin and tonic than to the rest of us, ‘In the last ten years I’ve had several hundred Indian and Pakistani and lately Africans in my graduate courses, and I’ve given out many an ‘A,’ and never flunked any of them; and there hasn’t yet been a single one who was a really first-class student.’”

Elsewhere in Suicide of the West, Burnham heaps scorn on the efforts of the Kennedy and Johnson administration to end food insecurity in poor countries—projects which led to the Green Revolution, sparing millions of lives in India and elsewhere.

Yet if Burnham had little use for Indians and Africans as scholars and harbored no concern for preventing their starvation, he does see a use for them as soldiers. “There have been few better fighting formations than the elite brigades of Gurkhas or Sikhs trained and led by professional British officers,” Burnham wrote in Suicide of the West. “Those tall, powerful black and brown men that France recruited from a French West Africa and trained in the tradition of Gallieni and Lyautey were nearly as good, though….These splendid fighting men of the Gurkhas, Sikhs, Senegalese and Berbers are not the least of the grievous losses that the West has suffered from the triumphs of decolonization.”

Burnham’s loyal and fighting trim Gurkhas and Sikhs are the military counterpart to Raspail’s Hamadura. Such figures function in the right-wing imagination in the crucial role of the ethnic sidekick, providing the sort of support that the Lone Ranger received from Tonto and the Green Hornet from Kato. Their skin color might be non-white, but they are trustworthy defenders of the West, as eager as D’Souza to fend off any Kenyan anti-colonial threats.

Thanks to the help of Jeffrey Hart, D’Souza started writing for National Review in 1981, while still an undergraduate. D'Souza adopted the ideological prism of his National Review mentors and carried it duly, proving his loyalty to the American ideal by championing white culture and showing contempt for its black counterpart. Obama's election in 2008 created a niche on the right for a person of color—an immigrant, even—to slag the president as being un-American. D'Souza had been preparing for such a role since college.

One of the saddest things about D’Souza’s racism is that it’s clearly built on some element of self-hatred. By aligning himself with figures like Hart and Burnham, he chose a form of upward mobility that required abasing himself before those who despised his heritage.

Most South Asians do not follow such a dim path. D’Souza and many others have benefited from the African American Civil Rights Movement. Prior to 1965, America set severely restrictive quotas on immigration from non-white countries such as India. The creation of a more generous and less racist immigration policy came about as a direct result of civil rights agitation and the work of liberals such as Ted Kennedy. Going back at least a century, South Asians and African-Americans have made common cause in fights against colonialism and racism: It’s no accident that Martin Luther King Jr. cited Gandhi as a predecessor, or that Bayard Rustin supported Indian independence. In choosing to align with and carry on the imperial nostalgia of Burnham and Hart, D’Souza betrays that less profitable but ultimately richer tradition.

Jeet Heer is a senior editor at the New Republic. @HeerJeet

Source: newrepublic